Learning Objectives

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the anatomical and pathophysiological changes that occur with adhesive capsulitis.

- Describe the associated stages of adhesive capsulitis and the signs and symptoms of each stage.

- Discuss the clinical presentation of adhesive capsulitis and associated differential diagnosis considerations.

- Discuss patient classification and treatment strategies based on irritability level.

- Develop and evidence-based treatment program for patients with adhesive capsulitis.

Introduction and Overview

Adhesive capsulitis and the term frozen shoulder are often used interchangeably. As stated by Dr. Codman, "It is a condition difficult to define, difficult to treat and difficult to explain from the point of view of pathology." It is often used to refer to any shoulder condition consisting of pain and limited range of motion. As clinicians, this presents a significant challenge for us, because people often present with a painful shoulder and limited range of motion, and many times they are erroneously grouped into this category of adhesive capsulitis. As we go through the material today, I would argue that there are a number of different shoulder ailments that can present with pain and limited ROM; how we approach each of them will be a bit different, depending on if it truly is adhesive capsulitis or another condition.

Clinical Controversy

There are a few questions that ultimately need to be addressed with regard to true adhesive capsulitis vs. a stiff, painful shoulder with limited ROM. Are they the same thing? Should the treatment approach be different? Is aggressive treatment the most successful?

Throughout our presentation today, we will demonstrate that the intensity of treatment is going to hinge on the individual presentation. There will be patients that will tolerate more aggressive or more forceful intervention. If we take an intense approach with other patients, we're potentially going to make them worse rather than better.

One of the challenges that we have in healthcare is the idea of a self-limiting condition. In other words, if we leave these individuals alone, they'll get better on their own. From an authorization standpoint, for being able to treat these patients, that can provide challenges. There is a lot of existing literature to indicate that if we provide no treatment, over the course of 1-2 years, people with adhesive capsulitis are going to be fine. If that is the case, some people would ask why should insurance pay for physical therapy or surgery or any medical intervention? However, if anyone has ever had adhesive capsulitis or any type of pain for that matter, two years is a long time to be in that level of discomfort and to have it impact your functional activity and your overall life. The glass-half-full side is that many people will indeed improve or get better in time with no treatment or intervention. On the other hand, we also have studies showing that patients experience symptoms and limited impairments for as long as three or even 10 years out. Commonly, the literature focuses on symptomology, and not so much on function. In fact, these people will often report that their pain improves, which is part of the natural history of adhesive capsulitis. Unfortunately, although their pain improves, they continue to have significant limitations in range of motion and strength deficits, which is going to impact their day-to-day function. That does not necessarily represent a full recovery or complete resolution of symptoms.

Studies

We will review several studies that have been conducted on people with adhesive capsulitis (AC). This is not an exhaustive list by any means, but a sampling of the literature showing both sides of the coin involving varying degrees of medical intervention.

- In The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS), Grey conducted a study in 1978. They had a group of 25 people to whom they provided analgesics and reassurance, essentially telling them to stick with it, everything's going to be fine. They conducted a two-year follow-up, and 24 out of 25 people reported they had absolutely normal function.

- In Orthopedics in 1996, Miller et al conducted a study of 50 patients that were treated with only heat and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. At the four-year follow up, 100% of their patients reported normal function of the arm and minimal residual arm pain.

- Again, in JBJS, Griggs led a prospective study of 75 patients with adhesive capsulitis in 2000. Of those 75 patients, 90% reported success with using only a stretching program, and that their ROM improved (flexion improved by 43 degrees, external rotation improved by 25 degrees). Although those numbers are significant, many people present with elevation and flexion that is 90 degrees or even less. Increasing that by 43 degrees is an improvement, but it is certainly not considered normal range of motion. With regard to external rotation, many patients have zero degrees or just five or 10; increasing it by 25 is a significant improvement.

- In 1992, Shaffer and colleagues published the findings of their study in JBJS. This group consisted of 62 patients, all with adhesive capsulitis. Interventions included physical therapy, nonsteroidal medications, injections and MUA as manipulation under anesthesia. At the seven-year follow-up, 50% reported mild pain and stiffness, 60% still had restricted motion and only 40% demonstrated symmetrical motion.

- A study in the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery (Hand et al., 2008) demonstrated that 50% of subjects had residual mild pain and decreased motion.

We have to be cautious when we're interpreting some of these papers. The mobility of the subjects may have improved from baseline assessment, but they are still not necessarily back to what we could consider "normal function" or full range of motion. While there are studies suggesting that people do in fact improve without intervention, there are other studies to show that they still experience pain, stiffness, and limitations in their day-to-day functional mobility and ADLs. As a physical therapist, that is a concern, and it is an area where we can potentially provide a positive impact.

Another important factor to consider when reading through many of these studies, they often look at patient-based outcomes rather than objective data. In other words, they use self-report questionnaires; they ask the patient what percentage improvement they think they have achieved. While obtaining patient feedback and opinions can be valuable, these reports are often subjective and based on emotion. The early stages of AC are exquisitely painful. As patients progress and as their pain lessens, they report that they're much happier, even though they still don't have full motion. In addition to pain relief, we need to make sure that we're also maximizing the patient's function, their range of motion, and restoring their strength back to baseline or back to normal.

Definitions

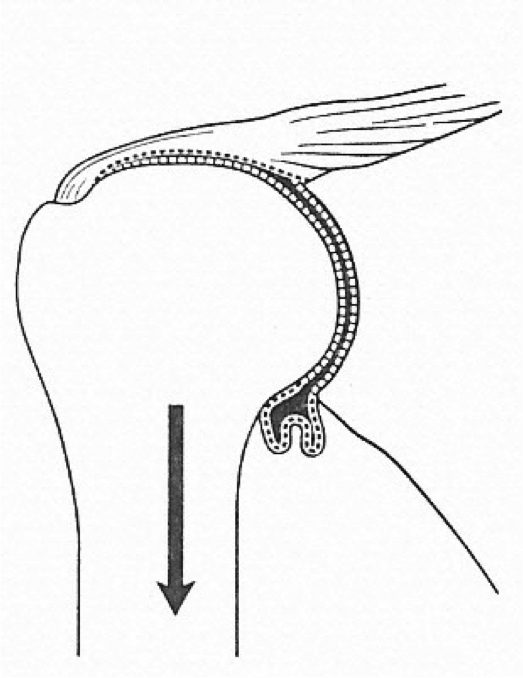

In as early as 1945, Doctor Neviaser defined adhesive capsulitis in JBJS as "an inflammatory reaction of the capsule and or the synovium that subsequently leads to the formation of adhesions in the axillary fold and the attachment of inferior capsule to the anatomic neck." Figure 1 is a diagram of a right shoulder from the front. We are able to see the scapula, the glenoid and the head of the humerus. Normally, we have what's referred to as an axillary recess; this capsule should be almost hanging down a little bit more. That recess is what allows the head of the humerus to glide inferiorly as we elevate the arm. As the humerus comes up (whether that's through abduction or flexion or scaption), the head of the humerus begins to glide down. With adhesive capsulitis, we start to see changes including adhesions and an obliteration of the axillary recess, which essentially prevents the head of the humerus from gliding inferiorly.

Figure 1. Right shoulder with adhesive capsulitis.

Zuckerman and Rokito published a paper in the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery in 2011, which defined frozen shoulder as "a condition characterized by functional restriction of both active and passive shoulder motion, for which radiographs of the glenohumeral joint are essentially unremarkable, except for the possible presence of osteopenia or calcific tendinitis." One of the hallmark traits is restriction in active and passive range of motion. If I refer back to where we started the talk, thinking about adhesive capsulitis versus stiff painful shoulder, people with rotator cuff problems and other pathologies of the shoulder will often have a limited range of motion. One of the bigger differences is seeing that limitation with both active and passive ROM. If you have a rotator cuff tear, your active range of motion is going to be limited, because you don't have the normal force couples working. Frequently, the passive range of motion, while it may not be normal, is going to be better than the active. From a differential diagnosis standpoint, we'll look at this in more detail, but with adhesive capsulitis, you're going to see both active and passive range of motion being restricted. With regard to radiographs, there is typically not a lot that you can see, except possibly osteopenia or calcific tendinitis, which may be secondary signs of adhesive capsulitis.

Zuckerman and Rokito break down the classification of a frozen shoulder into primary and secondary.

- Primary adhesive capsulitis is defined as a "diagnosis for all cases for which the underlying etiology or associated condition cannot be identified." In other words, patients that come in with no definitive mechanism or pre-disposing event that occurred are considered to be in the primary category. For these individuals, it is truly an insidious onset. The majority of papers and literature on this topic seem to be in agreement that the vast majority of patients presenting with adhesive capsulitis fall into this primary category.

- Secondary adhesive capsulitis includes "all cases of frozen shoulder in which an underlying etiology or associated condition can be identified." Our subjective history and patient intake forms become valuable with these individuals, so we can ascertain in whether they fall into the primary or the secondary category.

The secondary category of frozen shoulder can be further divided into three sub-categories: intrinsic, extrinsic, and systemic.

- Intrinsic adhesive capsulitis occurs in association with another condition inside the shoulder, such as rotator cuff disorders, biceps tendinitis, or calcific tendinitis. There's something going wrong in the shoulder that's now going to create a problem. For example, a person whose shoulder hurts due to an internal condition; they avoid movement and ultimately they begin to experience stiffness.

- Extrinsic adhesive capsulitis involves something outside of the shoulder. There is an identifiable abnormality remote to the shoulder itself but in the same vicinity. This includes people that have had a mastectomy, people with cervical radiculopathy, those who have had a stroke or heart attack, humeral fracture, AC arthritis. Again, something outside of the shoulder joint itself, but near enough that it is going to impact the soft tissues surrounding the area, and may create the need for immobilization.

- The systemic component within secondary frozen shoulder is associated with disorders such as diabetes, thyroid conditions, and hypoadrenalism. I would argue that the number of people we label as having primary adhesive capsulitis may be a bit too high. In other words, as we look at medical history, we are likely to find that there is a large cohort of patients who have some form of diabetes or another systemic disorder. Often, a person will come in and they did not have a fall, they did not have trauma, and they did not have surgery. However, rather than presuming they are in the primary category, we need to look at underlying medical factors that may suggest diabetes. We will review some of the literature that points to diabetes as a systemic cause of AC.

Frozen Shoulder: Clinical

Dr. James Cyriax is considered by many as the grandfather of orthopedic physical therapy and manual therapy. He was the first to define three main stages of adhesive capsulitis, which were derived from a clinical examination viewpoint. He broke it down into the freezing, frozen and thawing stages. Even today, these stages are still very much part of our thought process. With the advent of arthroscopy, we have expanded on these three stages a bit (I'll talk more about that coming up), but I think that Doctor Cyriax's work is still very important and worth reviewing. One thing worth noting, however, is that the range of time within the different stages is incredibly variable.

The freezing stage, which can last anywhere from one to six months, is similar to acute presentations. They have significant but vague lateral arm pain. In other words, it hurts a lot, but it's a more diffuse and not easy to pinpoint; but the pain is fairly significant.

The frozen stage, anywhere from six to 12 months in duration, is when things start to feel better. This brings us back to the self-limiting component. During the freezing stage, things are very painful. ROM is limited mainly because patients don't want to move because it hurts. In the frozen stage, we start to see the synovitis getting better. The pain is not as significant, but there have been adaptive changes within the capsule and there is more stiffness. Whereas the freezing stage is marked by significant pain; the frozen stage is much more marked by significant motion restriction. Not that it's pain-free, but it's not as painful as the freezing stage. I bring that up because that's a significant component for us to consider when we're trying to get a sense of where they're falling within this continuum. As we talk more about the stages that your patients are going through, I think that impacts our education and how we're talking to patients about what to expect. It's certainly going to dictate and guide our decision-making for intervention as well.

Most of the capsular patterns that we have for different joints came from Dr. Cyriax. It is a pattern of motion loss from most significant to least significant. He talked about external rotation being the most significant limitation, followed by abduction, followed by internal rotation and flexion. For a lot of patients, we'll see that the presence of capsular pattern doesn't always hold true. For a long time, that was part of my diagnostic criteria as far as determining if they truly have adhesive capsulitis, or if they have a painful stiff shoulder that might be something else: I was looking for that capsular pattern. That is probably less helpful from a diagnostic criteria standpoint but, using more recent literature, I’ll give you some good thoughts as far as how to look at these patients to make our determination of how we should classify them.

In Dr. Cyriax's model, the third and final stage is the thawing stage, the duration of which is anywhere from 12 to 24 months. Again, we're talking about two years potentially for some of these people. The thawing phase is typically when the resolution of impairment is happening. The pain continues to get better; they're starting to move more and the range of motion starts to improve. Part of the reason that I shared some of the articles with you at the start is that there's not this magical occurrence that happens and we flip a switch and now all of a sudden there's no pain and full range of motion. Pain gets better, range of motion improves, but with many patients that have been studied, there continues to be limitations, both in range of motion and strength. Things do start to improve; realistically, however, true resolution of impairments back to baseline is not always the most accurate presentation.

Frozen Shoulder: Arthroscopic

As I stated earlier, with the advent of arthroscopy, we started to be able to get a better sense of what's happening inside the joint. Dr. Cyriax originally proposed three stages: freezing, frozen and thawing. Thanks to technological advances, we have added a fourth stage that occurs before the original three: pre-adhesive.

Pre-Adhesive. Duration of symptoms during the pre-adhesive stage is up to about three months. This is where the inflammation of the synovium is first beginning. There are little to no capsular changes. There is some irritability within the joint, but no adhesions. There are little to no limitations in mobility. They may have a little bit of end-range pain with active and passive ROM. Keep in mind that vague lateral arm pain in the deltoid region can be common; the challenge is that very often the presentation or location of symptoms is very similar to what we see for rotator cuff impingement, biceps tendonitis, etc. If there is no clear mechanism that occurred to result in one of these conditions (e.g., painting the ceiling all weekend, pitching batting practice for their child's little league team), this pre-adhesive stage of frozen shoulder should be on our radar. If we catch it early and try to maximize their motion and minimize the motion loss, that can have a positive impact on their outcome.

Very often, these individuals are misdiagnosed with rotator cuff impingement or limited external rotation with intact rotator cuff strength. With true impingement or cuff disorders, you're typically going to have some weakness or some impact to the rotator cuff. People in this early phase of frozen shoulder will often have a little bit of limitation with external rotation, but their strength in mid-range is usually fine. Whereas someone that truly has a rotator cuff impingement, the rotator cuff strength may not be terrible but it's usually not going to be normal either. I think that's going to be potentially a helpful piece to allow us to differentially diagnose some of these presentations in the early stage.

Acute Adhesive. This stage falls in line with what Doctor Cyriax called his freezing stage. Duration of symptoms in this stage are between three and nine months. The acute adhesive stage is where we see much more significant synovitis, whereas in the pre-adhesive stage, the synovitis is just beginning. If you could imagine seeing an intra-articular view in this stage, the synovitis is very reactive. It can best be described as a red angry joint. It's that reactive red angry synovitis that is causing the pain in this phase, where people are in pain even at rest and the pain gets worse with motion. We also start to see early capsular adhesions and loss of joint space. One of the critical things, probably even more so than the capsular pattern that Doctor Cyriax described, is that you'll typically see limited motion in all planes. In other words, every direction has limitation in it. For me, that has become a bigger determining factor, rather than purely identifying the absence of the capsular pattern. Often, I'll have patients referred to physical therapy with a diagnosis of frozen shoulder, adhesive capsulitis, and they have lots of pain with external rotation. But if you ask them to raise their arm over their head, they have no problem: full of range of motion and very little pain. When that occurs, I automatically think of something else, because with typical adhesive capsulitis, with true frozen shoulder, you're going to have limited mobility in all planes. You may see one that's more limited than another, but there's typically going to be motion loss in every direction.

Fibrotic. Stage three is referred to as the fibrotic stage, or what Doctor Cyriax would call his frozen stage. Duration of symptoms is between nine and 15 months. In the frozen stage, the pain is improving and the primary complaint is stiffness. That's not to say that they don't have pain, but in the early stage, they typically will even have pain at rest which worsens with movement. In the fibrotic stage, the pain at rest has subsided and is generally only with movement because now the angry, intro-articular synovitis is starting to calm down. It's not as red and reactive; it's more of a pinkish hue, as far as how the inside of the joint looks. One of the things that I'll often ask to try to help determine where are they on this continuum, is if they are they able to sleep through the night. Typically, in acute presentation of freezing stage, people have significant difficulties sleeping through the night, because any movement that they make or if they lie on that side, irritates that synovitis and they'll wake up with symptoms. As the synovitis improves, they are usually able to get a reasonable night's sleep.

In the fibrotic stage, patients definitely have limitations in motion, and we can start to appreciate more of a stiffness or tightness within that end-feel, and we are able to feel that change in the capsular tissue; in the freezing stage, it's more often going to be an empty end-feel. They may have restriction but the pain is more significant; it's not allowing us to get into that range. Very often people will have injection at this stage, however, if the synovitis is improving, intra-articular injection often doesn’t change things very much. Motion at this stage is not restricted because of pain or inflammation as it is in the freezing stage. In this stage, it's restricted by capsular changes; as such, injecting cortisone into the joint isn't going to loosen the capsular tissue. There is a place for injection for our patients, but depends on where they are on the continuum as far as whether it's going to be helpful.

Pain presentation in the fibrotic stage is typically end-range. The pain they experienced while at rest in the freezing stage is typically better. These people will still have end-range pain, and often will still have night pain, but usually it's when they're moving in bed or they get into a position where they're laying on the shoulder. There's usually a cause and effect, versus it just being painful all the time.

Chronic Adhesive. Stage four is the chronic adhesive stage, which Doctor Cyriax referred to as the thawing phase. Duration of symptoms are between 15 and 24 months beyond the onset. The biggest change here is now there is very little pain and almost no synovitis. The pain is now either gone or very limited compared to where it was initially.

When you look inside the joint, on arthroscopy, you can still see very mature adhesions and significant restrictions within the joints. Within the capsular ligamentous structure, things aren't moving. I talked earlier about that obliteration of the inferior part of the capsule, that axillary recess, that tends to be where there is a lot of scar tissue, it's going to prevent the normal inferior translation of the head of the humerus. The synovitis and reactivity are better, but you are left with the limited mobility because of the challenge to the capsular tissue. The question becomes, is this when resolution of symptoms happens? For many people, the pain is better. It doesn't hurt to move, so they can have limited motion. Because it doesn't hurt, most people are much happier in this stage, even though they don't have full mobility. As physical therapists, we need to examine how we are defining recovery or resolution of symptoms. Our patients may be happier now that their pain is better, but is their function back to where it should be?

The reason for going through the different stages is to make sure that we understand that those stages are not distinct or individual, but it's a continuum: you transition from one to the next. There are also some in-between periods as well. You're not jumping over a stage; you're not jumping from the freezing stage into the thawing stage. You're going to go through all of those components. I think that that's an important process when we're educating our patients on initial evaluation. Where they're falling within that continuum is going to play a big role for our approach as far as what we think about for our examination as well as for our interventions as well.