Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Discuss the impact of social determinants of health on physical and behavioral health outcomes.

- List at least three outcome measures that can be used to screen for behavioral health concerns.

- Describe at least four resources that physical therapists can leverage during their treatment to optimize outcomes for patients with behavioral health concerns.

Introduction

Let's look at the global epidemic of behavioral health issues. Currently, it seems more uncommon for our patients not to face some form of behavioral or mental health challenge. The majority of individuals you encounter likely experience varying degrees of such challenges. We'll explore the implications of this on our outcomes in physical therapy and discuss possible interventions.

Definition of Mental Health

Let's begin by establishing some definitions to ensure that we're all on the same page and using consistent terminology. When we refer to "mental health," we're discussing how effectively someone functions in their daily activities. This encompasses their ability to engage in productive activities at work, school, and in caregiving, fostering healthier relationships, and adapting to change while coping with adversity. The recent years have imposed constant adaptation to significant changes in highly stressful situations, making these margins slimmer for many.

On the other hand, the term "mental illness" encompasses all diagnosable mental disorders and health conditions. Typically, mental illness involves significant changes in thinking, behavior, and potentially emotions or affect. It often brings about distress and difficulties in social, work, or family activities. It's important to note that mental health concerns may not necessarily result from mental illness. Some individuals with mental illness manage well, at least in certain moments, indicating that their mental health is okay. While the terms are not synonymous, they are interconnected.

Now, let's explore the term "behavioral health." Some of you may have wondered about this when you saw the title of this lecture.

What is Behavioral Health?

Behavioral health serves as an umbrella term encompassing individuals facing mental health issues, substance abuse conditions, various life stressors or crises, stress-related physical symptoms, and health behaviors. Essentially, it describes how we cope with and interact in response to our mental health or mental wellness.

It's crucial to recognize that conditions related to behavioral health often impact medical illnesses. I assume everyone taking this course is familiar with the biopsychosocial approach to care. You can think of the behavioral aspect as falling under the "psycho" part of that biopsychosocial umbrella, and that's primarily where our focus will be in this course.

Integrative Behavioral Health: Defined

Let's discuss the concept of integrative behavioral health. This framework for healthcare involves approaching a medical condition, let's say, for example, low back pain in physical therapy. With an integrative behavioral health approach, it means that in addition to providing the expert care that all PTs are familiar with—such as tissue-based care, exercises, and other established practices—you are also incorporating a proactive awareness and consideration of factors beyond the immediate physical aspects that can impact health and wellbeing.

This approach aligns with the concept of whole person care, representing a noteworthy shift in the medical field, albeit perhaps not as swiftly as needed. It emphasizes viewing individuals holistically, recognizing that addressing various factors affecting health contributes to comprehensive care. In essence, integrative behavioral health can be seen as essentially synonymous with biopsychosocial care.

Prevalence of Any Mental Illness (AMI) Among U.S. Adults

Turning our attention to the prevalence of behavioral health issues, the data I'll share is from 2019, as more recent studies are not available for a comprehensive update. It's important to note that the numbers discussed here likely underestimate the current situation, with a reasonable assumption that the prevalence has increased significantly since then.

According to the most recent study from 2019, encompassing a broad spectrum of U.S. adults, over 50 million individuals aged 18 and over had a diagnosed mental illness. However, it's widely acknowledged that the diagnosed number falls short of capturing the full extent of the issue. What's crucial to grasp from this data is that at least one in five U.S. adults has a diagnosed mental health disorder or mental illness. This implies that a substantial portion of individuals seeking care in your clinic likely grapple with some form of behavioral health challenge.

Additional statistics on the slide provide insights into specific demographics at higher risk, such as females, younger individuals, and those identifying with two or more races. These groups are more susceptible to diagnosed mental illnesses. Notably, a national survey on drug use and health in 2019 revealed that among the 50 million adults with diagnosed mental illnesses, less than half received any form of mental health services. This gap underscores the need for increased awareness and proactive engagement in addressing behavioral health concerns.

Not surprisingly, more females received mental health services than males, and younger adults, unfortunately at higher risk, were less likely to access these services. Researchers attribute this trend to factors like accessibility and cost, as mental health services can often be prohibitively expensive for individuals in these age categories and other high-risk groups.

Turning our attention to the mental health of children, while the data I'm presenting is from 2019, it's worth noting that mental health challenges for adolescents have been extensively documented to have increased during the pandemic. While I don't have precise statistics to share, in 2019, almost half of adolescents had a diagnosed mental disorder. Of those, about 22% experienced severe impairment. This indicates a significant vulnerability within this age category, highlighting the need for heightened attention to the mental well-being of adolescents.

The Concept of Trauma

Let's touch upon trauma, though it's important to note that I won't go too deeply into the topic. For those interested in a more comprehensive exploration of trauma-informed care, a webinar on PhysicalTherapy.com is available for further detail.

The significance of understanding trauma lies in its strong association with the development of mental illness and behavioral health concerns, particularly when considering Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which we'll briefly cover. Trauma can result from a single event, a series of events, or specific circumstances. The critical factor determining the impact of trauma is whether the person experiencing it perceives it as traumatic.

It's crucial to recognize that individuals may respond differently to similar situations based on their unique framework, which includes their background, brain chemistry, and various other factors. What may be highly traumatic for one person might not affect another in the same way. This distinction does not imply oversensitivity or resilience; rather, it underscores the individualized nature of trauma responses. It's essential to acknowledge that you cannot assess how traumatic an event was for someone else; you can only evaluate its impact on your own experience.

Trauma - Informed Care Approach

The trauma-informed care approach recognizes that a significant number of individuals have experienced trauma. Whether you're in a client-facing or staff role, it involves being able to identify signs and symptoms of trauma. Those adopting this approach integrate trauma knowledge into their policies, procedures, and practices, ideally at an organizational level, but at the very least, on an individual level. An essential aspect of trauma-informed care is actively working to prevent re-traumatization, even when it's not intentional.

While it's unlikely that anyone taking this course would purposefully seek to traumatize their clients, it's crucial to understand that certain medical procedures or experiences related to physical issues can, unknowingly, be traumatizing. This realization often becomes apparent through increased training in trauma and trauma-informed care. Simple medical procedures or routine experiences that we may take for granted can have unintended re-traumatizing effects on patients based on their past history and experiences.

An illustrative example is spinal manipulation, a technique frequently employed for individuals with spine disorders. While it's proven to be effective in interrupting cycles of low back pain and improving neuromotor function, a recent paper emphasized the importance of screening individuals to understand their beliefs and past experiences regarding spinal manipulation.

Regardless of the proficiency or the explanation of a technique, such as spinal manipulation, a patient's past history can significantly impact the outcome. Even with flawless execution, if a patient has had a negative experience with manipulation, potentially from a different healthcare provider, the belief that the technique is dangerous can trigger a stress response, potentially causing harm. This doesn't reflect on the provider's skill, the appropriateness of the technique for the symptoms, or the overall effectiveness of spinal manipulation. Instead, it emphasizes the importance of recognizing potential trauma-related triggers in patient care.

Understanding which components of care might be linked to a patient's traumatic experience is crucial. If there's a possibility, asking questions, fully explaining procedures, and seeking the patient's input become essential. This approach ensures that the patient feels heard and understood, fostering trust in the therapeutic relationship. Research supports the notion that, in cases of past trauma, proceeding with certain interventions may do more harm than good, even if the treatment aligns perfectly with the symptoms.

It's important to clarify that this discussion is not meant to discredit spinal manipulation; rather, it highlights the need for a patient-centered approach. Although spinal manipulation is a valuable and frequently used treatment, this example serves to underscore the significance of actively involving patients in decision-making, particularly when there's a potential link to past traumatic experiences.

Trauma and ACE’s Impact on Integrated BPS Model

Let's touch on Adverse Childhood Experiences, commonly known as ACEs. For a more -in-depth exploration, I recommend checking out the Trauma Informed Care webinar. ACEs refer to adverse events occurring during childhood, spanning the ages of zero to 18. Research has shown a significant correlation between ACEs and the subsequent development of various health problems, encompassing physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral aspects.

What's particularly striking is the establishment of a dose-response relationship. This relationship indicates that the higher the degree of exposure to childhood trauma, the more closely it's linked to major health conditions that stand as leading causes of death in adulthood.

These adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are not limited to affecting mental and behavioral health; they extend their influence to physical health as well. Major health conditions such as cardiac disease and cancer, traditionally perceived as purely physical, have now been closely linked to ACEs. It's essential to grasp that far more individuals have encountered at least one ACE than those who haven't. Moreover, the number of people who have experienced two or more ACEs is comparable to those who haven't experienced any.

This underscores the prevalence of ACEs in the population, emphasizing that individuals under your care or seeking your assistance may already carry these experiences as part of their background history. The goal of this course is to raise awareness and equip you with a framework or toolbox to recognize and address ACEs.

Types of ACEs

These are examples of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which can be categorized into abuse, overall childhood challenges, and household challenges. Examples of the latter include substance use in the home and having incarcerated household members. While not explicitly mentioned on the slide, growing up in a low-income household below the poverty level also falls into this category, along with neglect.

Mechanism by Which Adverse Childhood Experiences Influence Health and Well-Being Throughout the Lifespan

As mentioned earlier, adverse childhood experiences can significantly impact health and well-being throughout one's lifespan. These experiences may manifest in infancy or later in life, depending on various factors. Because these events occur before the maturation of the frontal lobe—responsible for reasoning and processing complex events—children lack the cognitive tools to shield themselves or make sense of such occurrences. The extent of neurodevelopmental disruption varies based on factors such as age and the intensity of exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Consequently, this disruption can lead to varying degrees of social, emotional, and cognitive impairment.

Due to the lack of frontal lobe maturity, the foundation for an individual's resilience and capacity to navigate change or difficulty is still forming. Often, individuals may adopt what are termed 'health risk behaviors,' which increase the likelihood of future health issues, such as substance utilization or alcohol consumption. This behavior is often an attempt to self-soothe, as individuals lack the internal capacity for emotional regulation. Unfortunately, this hinders the development of healthy coping mechanisms within their own minds. Consequently, these health risk behaviors can lead to the onset of disease, disability, and social problems.

Extensive research has established a clear link between higher levels of ACEs, especially exposure to more severe instances, and a shortened lifespan. Individuals with elevated ACEs are known to experience premature mortality compared to those with fewer or no ACEs. This underscores the profound and lasting impact of ACEs on individuals, affecting them from conception to death. However, it's essential to emphasize that all hope is not lost.

PACEs

However, there's also a concept known as PACE, which stands for Positive and Adverse Childhood Experiences. PACEs serve as a measure of resilience or positive experiences that can counterbalance the impact of adverse childhood experiences. These positive experiences have been associated with higher levels of education, increased income, and improved mental well-being, effectively mitigating the effects of ACEs.

Current understanding of PACEs includes elements such as nurturing relationships, enhanced neurodevelopment, and the ability to make healthy choices. Importantly, practitioners have the potential to assist clients or patients in developing PACEs, even in the presence of ACEs. This can significantly offset the negative impact of adverse experiences. It's crucial to note that PACEs are inherently relational, and we will delve into encouraging healthy relationships later in this discussion. The key takeaway is that it's never too late for individuals to cultivate supportive relationships that can counteract the challenges they may have faced during their childhood.

What is the Connection Between Trauma, Behavioral Health and Pain?

We recognize a strong link between trauma, behavioral health, and pain—knowledge that is critical in rehab services where pain is a frequent focus. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), alongside other traumas, heighten the likelihood of both physical and behavioral health disorders occurring simultaneously. The integrated biopsychosocial model under discussion serves as a tool for us to conceptualize client cases, comprehending the impact of past trauma and behavioral health concerns. However, it's vital not to overly focus on pathophysiology. While it may persist, our emphasis within the biopsychosocial care model is to ensure equal attention across all categories.

We don't want to dismiss behavioral health as someone else's responsibility while exclusively focusing on tissue issues. While we may not be mental health providers or experts in that field, I'm not suggesting that we try to replace counselors. However, we do play a significant role in letting our understanding of trauma, behavioral health, and Positive and Adverse Childhood Experiences (PACEs and ACEs) guide our interactions with patients. Additionally, we need to be proactive in recognizing when referrals are necessary.

While we may not provide mental health services directly, we contribute to a holistic approach by integrating our knowledge into patient interactions. Understanding the dynamic interplay of psychological, social, and biological elements, we offer an informed approach that considers the impact of the environment and individuals' behavioral health experiences on their physical well-being.

Physical Therapy and Behavioral Health?

A common question that arises is, "Is this within a physical therapist's scope of practice?" Interestingly, the APTA has addressed this concern, affirming their support for interprofessional collaboration at both organizational and individual levels. They advocate for advancing research, education, policy, and practice in behavioral and mental health to enhance overall societal health and well-being, aligning with their broader vision for the profession. Recognizing the inseparable connection between physical, behavioral, and mental health with overall well-being, the APTA explicitly states that it falls within the professional scope of a physical therapist and physical therapy practice to screen for and address behavioral and mental health conditions in patients, clients, and populations.

This endorsement doesn't imply replacing mental health providers. On the contrary, the APTA encourages appropriate consultation, referral, and co-management. The emphasis is on not dismissing concerns by simply advising patients to seek mental health care independently but rather recognizing our role in facilitating access to the care they need.

Prevalence of BH issues in PT/OT/Rehab

To provide a general overview, studies have delved into the prevalence of behavioral health issues in the fields of physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), and rehabilitation. When examining depression, especially within the context of common diagnoses treated in orthopedic clinics, there is notable variability in reported prevalence rates. This range is attributed to differences in study variables and percentages.

While we lack an exact number due to these variations, the key takeaway from this data is the documented relationship between depression and specific diagnoses. The nature of this relationship—whether it is causative or correlative—remains uncertain.

The studies haven't reached a definitive conclusion on this aspect yet, and this might not come as a surprise because we've observed this trend. Examining anxiety, the correlation tends to increase across most diagnoses. Turning to substance use, the prevalence is not as high as some might assume when making an off-the-cuff estimation. Nevertheless, there is an established relationship.

What we're advocating for is a paradigm shift within our profession. While it might not be the current practice for PTs, historically, there was a prevalent belief, rooted in Rene Descartes' ideas, that suggested a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship—especially concerning pain. This notion implied a direct correlation between tissue damage and pain, adhering to a rigid one-to-one relationship. However, in our approach to treating and working with individuals, we assert the necessity of considering their overall health, encompassing the biological realm where most physical therapists are well-versed. Yes, there may be tissue damage, but it's crucial to broaden our perspective beyond a strictly linear cause-and-effect paradigm.

Other physical health factors could contribute to or amplify this damage. Various comorbidities, illnesses, and other factors may be at play. It's essential to consider not only the biological aspect but also the psychological, social, and environmental dimensions. While many of our direct treatments understandably align with the biological realm, it's crucial to acknowledge the holistic impact of these factors on a person's overall health. Recognizing that these interconnected aspects can influence the response to our treatments is vital, as supported by recent studies. In essence, the effectiveness of interventions may be intricately linked to psychological, social, and environmental factors.

Integrative Behavioral Health

There are ways we can engage with individuals to either foster healing and wellness in all these areas, or not. It's up to us to figure out how to navigate that. Once again, as we consider an integrated behavioral health framework, we should view it as grounded in the integrated biopsychosocial model. Essentially, what we should focus on are action steps. Our goal is to understand the fundamentals of behavioral health. We may not become experts like those who've earned degrees in the field, and that's perfectly fine. Understanding the basics is what we aim for.

Within ourselves and in our interactions with patients, it's imperative that we acknowledge and honor the complexity of the human experience. It goes beyond a simple one-to-one relationship, a truth we recognize. To achieve this, we must work within ourselves to diminish the tendency to compartmentalize or engage in what's termed dualistic thinking.

In the early stages, especially when this topic might feel less familiar, there can be a temptation to categorize individuals. For instance, questioning why someone isn't coping the way we might, or labeling them as a "frequent flyer" or someone who tends to catastrophize. This inclination to place individuals in distinct silos can hinder our ability to provide effective assistance.

Recognize that this is a common human tendency and, if you catch yourself doing it, be kind to yourself. This learning process may require going against the natural inclinations of the human brain. Perfection isn't the expectation right away; it's okay to feel imperfect as you navigate this. Remember, practice makes perfect, or something like that, right?

Our approach should be rooted in empathy, compassion, and trust. What we aim for is to nurture an internal locus of control within our patients through patient-centered care.

This means engaging patients as active participants in their healthcare and healing journey. It's a departure from the older school of thought where the healthcare provider is seen as the expert fixing the patient. Instead, we adopt a coaching or supportive role, providing resources and standing alongside them. Ultimately, it's the patient's journey up the mountain, and while we can offer support and assistance, they are the ones who must take each step. Recognizing this and empowering patients accordingly has been robustly linked to achieving desired outcomes.

Moreover, acknowledging the contributions of various disciplines is crucial. In contexts where ideal services might be inaccessible due to financial or time constraints, we shouldn't dismiss the importance of alternative approaches. For instance, sharing informative podcasts or articles written by experts can be a valuable resource. While ideal services may not always be within reach, helping patients explore available options and find a good fit can still contribute to their well-being. These are tangible action steps we can take to enhance patient care.

Our Responsibility as Providers

Understanding trauma-informed care and recognizing the impact of ACEs and PACEs is crucial. We'll discuss identifying behavioral health symptoms through biopsychosocial assessments shortly, aiming to integrate this knowledge effectively.

Our goal is to incorporate an integrative behavioral health treatment framework into our individual approaches within clinical settings. Building your village involves developing a multidisciplinary team of providers. Even if patients can't directly access this network, the ability to draw from it is essential, though it may take time to establish. Personally, I've found it typically takes two to three years to form a reliable village or support network. Along the way, you may encounter helpful individuals who can contribute to your journey.

Screening for Behavioral Health Issues

Let's explore how to screen for behavioral health issues, a crucial step in an integrated framework for recognizing individuals who may benefit from a specific behavioral health approach.

Many of you might be familiar with the fear-avoidance model, often encountered in PT school or continuing education courses. This model suggests that individuals, when experiencing pain, can follow two pathways: one involving pain catastrophizing and the other avoiding such catastrophic thoughts. The former can create a loop hindering healing, while the latter facilitates recovery.

However, there's an updated version of this model that I find valuable. The update primarily involves the language used. In this new framework, individuals experience pain, and instead of framing it as pain catastrophizing, which implies a degree of choice, the focus shifts to how the person perceives the pain threat. It becomes a matter of whether the response to pain involves a high threat or a low threat.

If individuals experience a high threat in response to pain, their primary focus becomes pain control, potentially leading them into a challenging cycle. On the other hand, those who experience low threat prioritize their life goals despite the pain, aiding in the recovery process.

In both models, physical therapists play a crucial role in assisting individuals trapped in these cycles to transition towards a low-threat response. Now, for a practical understanding, let's consider what these concepts look like in practice. It's often beneficial to have a tangible grasp of these ideas.

Let's use low back pain as an example. A recent study revealed that approximately 80% of physical therapists experience at least one episode of low back pain during their careers—a fact that might not come as a surprise. What's interesting is that physical therapists, when faced with low back pain, often recover well. Why is that the case? It's because many of us are somewhat desensitized to most types of low back pain, excluding severe injuries requiring surgery. This desensitization is a result of our education and understanding that the majority of run-of-the-mill low back pain tends to improve whether or not intervention is applied.

As physical therapists, we benefit from a toolbox of interventions and knowledge that we readily share with our patients, offering active strategies to facilitate recovery. This contrasts with a patient experiencing low back pain for the first time, perhaps with a family history of someone severely impacted by such pain. In such cases, their brain, driven by its protective instinct, might leap to worst-case scenarios, creating a potential loop of fear and avoidance.

The reassuring aspect is that education can effectively disrupt this cycle. Recognizing the presence of high fear avoidance becomes crucial in identifying potential behavioral health concerns. Fortunately, there are well-validated and easy-to-use screening questionnaires available across various behavioral health concerns, providing us with valuable tools to identify and address these issues effectively.

Fear Avoidance Model

For assessing fear avoidance, many of us are likely familiar with the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, which has variations for both low back pain and non-low back pain situations. This questionnaire includes a Physical Activity Scale and a Work Avoidance Scale, providing flexibility in assessing specific areas of interest. A score of 15 or higher on these scales can indicate a likelihood of fear-avoidant behaviors or beliefs. Additionally, the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia is a valuable tool, measuring the person's fear of movement.

If individuals score in the higher risk range on these questionnaires, it serves as an indication that they might benefit from multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary care. Alternatively, integrating a behavioral health framework into our approach becomes essential. This may involve incorporating elements such as pain neuroscience education, cognitive-behavioral therapy, movement interventions, and other strategies discussed later in our conversation. These tools allow us to better understand and support individuals who may be struggling with fear avoidance and related behavioral health concerns.

(Pain) Catastrophization

Pain catastrophization involves anticipating the worst possible outcomes and perceiving situations as unbearable or impossible, even if they are merely uncomfortable. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale is a tool available for assessing these tendencies. While it's a useful scale, some clinicians may find that the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire or the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia provides more relevant information for their patient population.

Now, let's consider how to implement these assessments in the clinic, acknowledging the time constraints that we all face. It's challenging to allocate extensive time for paperwork, especially when patients might not always arrive early for it. Recognizing these challenges, here's a framework to integrate behavioral health assessments into your care. Understand that you don't have to incorporate all elements for every patient, but having a flexible approach can enhance the overall care experience.

When considering the use of outcome measures, it's beneficial to cast a wide net initially by assessing areas where patients are highly likely to face challenges. From there, you can tailor your approach based on individual needs.

In a typical initial visit, where you're already collecting demographic and insurance information, along with medical intake or review of systems, and functional scales such as Oswestry or NDI, consider incorporating a fear avoidance or a similar scale. This addition helps kickstart the process of risk stratification.

Now, let's delve into the practicality of measuring various aspects of mental health for all patients. While it may seem ideal, the reality is that it might not be feasible in your clinical practice. Thus, it's crucial to think strategically about who to measure for what after the initial screening process. This targeted approach allows you to allocate resources efficiently and provide more personalized care based on individual needs.

Symptom and Sign Cluster for Central Sensitization (Nociplastic)

Patients displaying signs and symptoms of central sensitization or experiencing nociplastic changes within the central nervous system are highly likely to encounter mental and behavioral health issues. It's important to note that this doesn't mean we should neglect screening for mental and behavioral health concerns in patients without central sensitization. However, a more detailed screening may be warranted for those with central sensitization.

Indications of central sensitization include disproportionate pain in response to movement and intensity of pain that doesn't align proportionally with the performed activity. These are individuals who struggle with simple movements like getting up from a chair or experience significant pain from such actions. Additionally, look out for those with disproportionate aggravating or easing factors. For instance, a patient who experiences severe pain for hours after just a short 15-minute drive.

Another telltale sign is diffuse palpation tenderness. Unlike patients who can pinpoint specific areas of discomfort, these individuals describe a broader area of tenderness, sometimes resembling a colored-in body chart that covers a wide range. These are the patients who likely benefit from more in-depth screening for behavioral health concerns.

Interestingly, commonly used outcome measures like the Oswestry and NDI may not be as responsive for individuals with central sensitization, particularly when compared to those with a more mechanical component to their pain. While these measures may show some responsiveness at the beginning and end of treatment, they were originally designed with a focus on mechanical aspects of pain rather than central nervous system changes.

Considering this, it could be valuable to incorporate the Fear Avoidance Scale and Pain Catastrophization Scale for everyone presenting with symptoms associated with central sensitization. These scales offer a more targeted approach to capture important aspects of mental and behavioral health. Depending on the identified high-risk areas during the initial screening, you might also consider administering specific screens for items related to central sensitization.

Screening for Depression

Much of this relies on your clinical judgment. However, the goal is to provide you with a framework for screening issues such as depression and anxiety. You likely already ask pertinent questions to heighten your suspicion of depression. Individuals may express tension, anxiety, or report a diagnosis of depression. They might also mention memory problems or note unusual mood changes, including new-onset issues.

Depression may manifest with sleep challenges. A noticeable shift in attitudes or mood towards family and friends could be indicative. Additionally, if you identify common antidepressant medications in their prescription list, it may further suggest a depression diagnosis.

Research indicates that approximately one in seven patients seeking outpatient physical therapy for musculoskeletal pain may have moderate to severe depression. This statistic is derived from a study involving around 320 patients.

Already within our patient population, we encounter individuals dealing with depression. This lecture emphasizes the importance of recognizing depression and explores how this recognition can shape our approach to care plans. Several variables are associated with elevated PHQ-9 scores, a depression screening questionnaire that I recommend due to its brevity and high validation.

The key variables linked to a higher likelihood of depression or elevated PHQ-9 scores include disability, personal injury insurance, and a high body mass index. It's crucial to note that these are correlations, not causations. I want to emphasize that I'm not suggesting any causal relationships; we lack that evidence. However, within these categories, we observe a higher prevalence of individuals experiencing elevated levels of depression.

Lower depression scale scores are correlated with increased sleep duration and higher levels of physical activity. It's encouraging to note that many interventions we are already implementing with our patients, such as promoting better sleep and encouraging exercise, align with factors associated with lower depression scores.

For efficiency or when time constraints arise, a two-question depression screening tool, known as the PHQ-2, can be a valuable resource. This abbreviated version of the PHQ-9 is highly sensitive. While it may not provide detailed information, it serves as a quick means to rule out depression during comprehensive screenings. A low score on the PHQ-2 is indicative that depression is less likely, offering a time-efficient way to eliminate this concern. However, it's important to understand that a high score on the PHQ-2 doesn't definitively confirm depression; further evaluation is necessary in such cases.

When utilizing the PHQ-2, exercise caution in its interpretation. While it offers a convenient two-question scale, a low score is suggestive of a lower likelihood of depression. However, a high score doesn't conclusively confirm depression; further evaluation is warranted.

The PHQ-2 comprises two questions—focusing on little interest or pleasure in activities and feeling down or hopeless—that may seem familiar, as they are commonly used in primary care settings. If an individual scores three or higher on the PHQ-2, it suggests a potential major depressive disorder. For instance, if they report little interest or pleasure in activities for several days and feel down or hopeless for more than half of the days, the cumulative score would be three, indicating a higher likelihood of depression.

Moving on to the PHQ-9, it provides a more comprehensive assessment with scores ranging from mild to severe depression. The associated treatment plans vary based on the severity of the depression. The PHQ-9 is easily accessible online, and a link is provided in your handout for reference.

It's crucial to pay close attention to question nine on the PHQ-9, which addresses suicidal ideation. If a patient indicates the presence of such thoughts, it necessitates further exploration and consideration, emphasizing the importance of a thorough inquiry into this aspect.

When a patient describes suicidal ideation—meaning they have thoughts of suicide without necessarily having a plan or intent—it raises questions about the healthcare provider's duty and responsibility. It's important to recognize that not everyone with suicidal ideation is at an immediate risk of attempting suicide. The frequency of these thoughts, however, does impact the likelihood of acting on them.

Understanding the frequency of suicidal ideation is crucial. While occasional thoughts are relatively common, increased frequency or the development of detailed plans can indicate a higher risk. It's essential to approach these situations with attention but without inducing panic, both for the provider and the patient. Many individuals, even without significant behavioral health concerns, may experience fleeting thoughts occasionally.

Monitoring the progression of these thoughts is key. If they become more frequent, detailed, or if a patient starts developing a plan, it may necessitate a more immediate response. Later on, we will delve into suicide prevention in more detail.

In addition to the PHQ-9 and PHQ-2, there are other depression assessment tools available. Although I personally do not use them, I wanted to provide you with information about these tools. Some of these are commonly used by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists. Familiarizing yourself with these tools can be beneficial for a comprehensive understanding of your patient's history and potential needs.

The Beck Depression Inventory

- 21-item, self-report rating inventory that measures characteristic attitudes and symptoms of depression (1961)

- Determines behavioral manifestations and severity

- 10 minutes to complete

- 13-item short form has similar reliability

- BDI-II by Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996 also has similar reliability

- High internal consistency, (alpha coefficient .86 for psychiatric populations; .81 for non-psychiatric populations)

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

- Measures depression in individuals before, during, and after treatment

- 21 items, but is scored based on the first 17 items

- 15 to 20 minutes to complete and score

- Used for over 50 years:

- Meta-analysis suggests that HRSD provides a reliable assessment of depression

- Figures indicate good overall levels of internal consistency, inter-rater and test–retest reliability, but some HRSD items (e.g., “loss of insight”) do not appear to possess a satisfactory reliability

Screening for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) has witnessed a significant increase during the pandemic, as expected. The diagnostic criteria for GAD are outlined in the DSM-5, a manual describing diagnosable mental health disorders. The key features of GAD include a sense of restlessness, feeling on edge, easy fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbances. To be diagnosed with GAD, individuals need to exhibit at least four of these criteria; it's not necessary to present all symptoms.

It's crucial to recognize that occasional anxiety is part of the human experience, and not everyone experiencing anxiety meets the criteria for a diagnosable disorder. The distinction lies in the impact on functionality. GAD becomes a diagnosable illness when it significantly hinders a person's ability to function in their daily life. This emphasizes the importance of assessing whether anxiety is a normal part of the human experience or if it has progressed to a level where it interferes with the individual's overall well-being. Understanding this distinction aids healthcare providers in determining the appropriate interventions and support for their patients.

The GAD-7 provides a systematic way to screen for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). This seven-item questionnaire boasts good validity and reliability scores, with established norms for interpretation. In terms of screening scores, the norms categorize individuals into different levels of anxiety severity, ranging from normal to severe.

It's noteworthy that in individuals with genuine anxiety, only 5% have scores of 10 or higher, and a mere 1% have scores of 15 or higher. The GAD-7, therefore, serves as a valuable tool to gauge the extent of anxiety in individuals.

In a clinical practice setting, the GAD-7 can be administered by having individuals respond to the seven questions, and their cumulative scores can then be calculated. This total score helps determine the severity of anxiety—whether it falls within the categories of minimal, mild, moderate, or severe. The GAD-7 serves as an efficient and reliable means for healthcare providers to identify and assess anxiety levels in their patients.

Example of Building a Profile...

Building a comprehensive patient profile involves a thoughtful approach over multiple visits. In the initial visit, you're likely gathering demographic information, conducting a medical intake review of systems, assessing functional measures, and obtaining pain ratings. Integrating additional assessments based on subjective clues obtained during the examination can enhance your understanding.

Consider adding a fear avoidance questionnaire and the PHQ-2 during the first visit. The PHQ-2, being concise, provides valuable information about depression. Depending on the outcomes, you can tailor your approach for the second visit. If depression is a concern, you might delve into more in-depth depression questionnaires. If catastrophization is an issue, specific questionnaires can assess this aspect. The GAD-7 for generalized anxiety can also be considered but may be deferred to the second visit, allowing a phased and patient-centric approach.

PTSD is not as widespread as commonly perceived, but it can manifest in specific patient populations. Individuals screening high for depression, anxiety, or catastrophization, especially those with a known post-traumatic event, may warrant consideration for PTSD screening. Traumatic events, such as military service or car accidents, can potentially lead to PTSD. While not everyone in a clinical setting may have PTSD, being aware of this possibility is essential.

Understanding whether a patient has PTSD is crucial because PTSD can trigger re-experiencing the traumatic event. For example, if a person has PTSD related to sudden stopping motions, it's vital to consider this when planning interventions. Plyometrics or sudden movements might not be suitable for someone with such a trauma history. Similarly, if wheelchair movement triggers PTSD symptoms, adjustments in wheelchair speed or movement may be necessary.

Screening for PTSD may be less common than depression and anxiety, but it's valuable to recognize that such screenings can offer crucial insights into a patient's mental health. If further detail is needed after a GAD-7 assessment, the SCARED screen (Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders) can be considered. This screening tool is particularly relevant for pediatric patients or individuals with significant anxiety not adequately captured by the GAD-7. While the name might raise an eyebrow, understanding and utilizing such specialized screening tools can be beneficial, especially in cases where anxiety-related disorders may require more focused attention. Awareness of available screening tools broadens healthcare providers' ability to address mental health concerns in diverse patient populations comprehensively.

For the majority of patients, the GAD-7 serves as an effective screening tool. However, when it comes to assessing suicide risk, a more specific tool such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale can be employed. Personally, I often rely on direct questioning about suicidal ideation, frequency, and whether there's a plan. If there is a plan, immediate action, such as calling a suicide hotline or 911, is necessary. For those experiencing distress without a specific plan, there are hotlines available, including text-based options for individuals uncomfortable speaking about it aloud.

Maintaining a list of these resources, whether in electronic or printed form, is crucial for healthcare providers. Sharing this information with patients proactively ensures preparedness for potential crises. Planning ahead is essential, and having these resources readily available can make a significant difference.

The interconnectedness of mental health issues, as discussed earlier, is underscored by their link to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Screening for ACEs is also available, providing additional insight during the intake process. There's a useful ACEs screening tool that can be easily found online. Furthermore, the website "ACEs Too High" offers a wealth of information and resources related to adverse childhood experiences.

Physical Therapy Management of Mental and Behavioral Health Issues

Now that we've covered some background and screening, let's delve into physical therapy management. But before we do that, I'd like to address a pertinent question that has come up. A participant asked, "Have you encountered patients hesitant to respond to behavioral and mental health questionnaires?" Unfortunately, yes, I have. Despite progress, there remains a pervasive stigma around mental health. To provide context, my specialization is in pelvic health physical therapy, focusing on treating individuals during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Many postpartum patients express fear that admitting to postpartum depression or anxiety might lead to their baby being taken away. This fear creates a significant barrier.

To address this concern, I make it clear that unless there is a genuine concern for the patient's safety or the safety of others, their responses are confidential. I reassure them that our discussions stay within the confines of our sessions. If the assessment indicates a need for additional support, I offer resources such as consulting with their primary care doctor for medication or recommending counseling services. The goal is to present options and empower patients to make informed choices regarding their mental health without fear of judgment or repercussion.

I want to emphasize that I won't impose any actions or reach out to others without your consent. Your well-being is my priority, and these assessments are tools to help me provide the best care for you. If you're not comfortable filling them out now, that's perfectly fine. We can revisit the conversation whenever you feel ready. I consider a refusal or concern about these assessments as not diagnostic, but it does raise suspicion that there might be underlying mental health issues or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). In my approach, I treat individuals in a whole person-centered way, acknowledging the possibility of these concerns.

Even if a patient doesn't disclose trauma or mental health issues, I believe in providing trauma-informed care. This approach is essential in fostering a safe and supportive environment for patients. For more in-depth information on this topic, I recommend checking out the trauma-informed care webinar mentioned earlier.

Moving on to a question about central sensitization, somatic symptom disorder, and malingering. While delving into extensive details may exceed our time constraints today, I'd be happy to provide a brief overview. Central sensitization is a real phenomenon, and its treatment is promising. It's crucial to understand that it's not imagined or solely psychological.

Somatic symptom disorder was indeed removed from the DSM-5. The underlying concept behind both somatic symptom disorder and malingering was the assumption that individuals were intentionally exaggerating or fabricating their symptoms. However, current understanding recognizes that such intentional exaggeration is exceedingly rare. While I won't claim it's entirely impossible, the complexity and diversity of human experiences suggest that every scenario, no matter how uncommon, may have occurred at least once.

Reflecting on my own education, there was a significant focus on identifying malingering in patients, particularly those involved in accidents or workers' compensation cases. However, contemporary knowledge suggests that such cases are infrequent. Moreover, approaching individuals with the suspicion of malingering can potentially cause more harm than good. Fortunately, our understanding of these issues has evolved, and it's crucial to approach patients with a more nuanced and compassionate perspective.

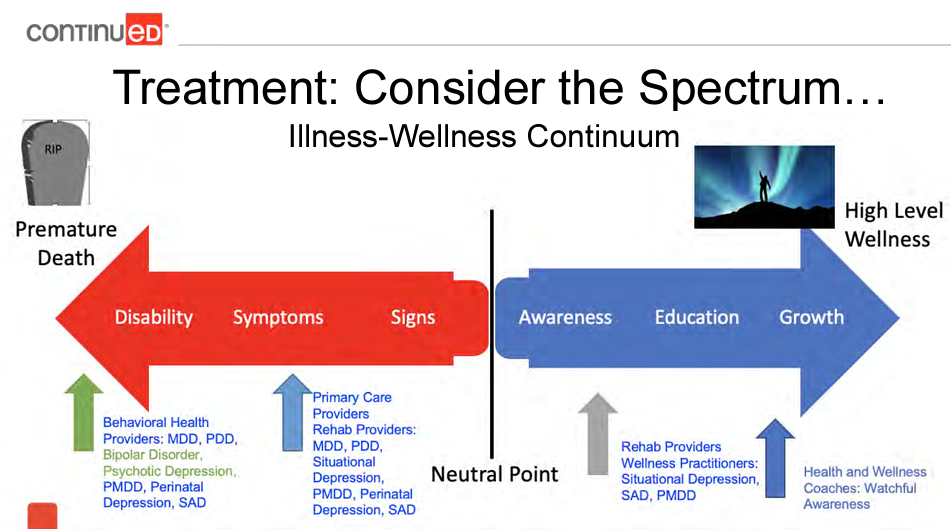

Treatment: Consider the Spectrum...

Mental health exists on a spectrum. It's not a simple binary of having a particular condition or not. The degree of symptomatology and disability varies, and the impact on an individual's ability to function in their self-defined life roles or societal roles is significant. While this may be a somewhat simplistic framework, it is a starting point for understanding the spectrum.

Figure 1. Illness-Wellness Continuum

Imagine the spectrum ranging from signs and symptoms to increasing levels of disability (Figure 1 left side) Unchecked, many of these mental health issues can lead to serious consequences, including early death. This underscores the importance of intervention and our role in facilitating or being part of the intervention process.

Simultaneously, there's another spectrum related to awareness, education, and growth (Figure 1 right side). Here, we have the opportunity to make a positive impact. Even for those with severe disabilities, our influence can be valuable, but in such cases, collaboration with physicians or behavioral health counselors may be necessary.

Whether it's signs, symptoms, or severe disability, our response should align with the spectrum of the individual's needs. It's about tailoring our approach to the unique circumstances of each person, recognizing that a one-size-fits-all response isn't effective in the realm of mental health care.

The Big Picture for Treatment

You may already be providing beneficial treatment for behavioral health concerns, whether or not you are consciously aware of it. Consider the evidence-based treatments we know for patients with persistent pain. Movement, in its various forms, has demonstrated effectiveness—whether it's yoga, Tai Chi, aerobic exercises, or simply encouraging any type of motion. The concept that "motion is lotion" holds true, emphasizing the importance of keeping our bodies in motion rather than stationary.

Calming the nervous system is another crucial aspect, and we, as physical therapists, contribute significantly to this through various means. Manual therapy, a common practice in many clinics, is one such approach. Stabilization training and aquatic therapy are also effective methods for achieving this goal. Additionally, addressing sleep hygiene has gained attention within the rehabilitation field, highlighting the impact physical therapists can have on promoting better sleep and overall well-being.

Know Your Role + Severity of Issue

PTs are not psychologists, and we are not attempting to replace their role in patient care. However, we should consider the ways in which we can complement the cognitive therapy that individuals might be receiving from mental health professionals.

Even simple interventions, such as mindfulness, can play a significant role in supporting patients. For those interested in a more in-depth exploration of mindfulness, there's a dedicated webinar available. Other approaches, like motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy, might initially seem more aligned with psychology, but in the physical therapy realm, they involve helping individuals reframe their thoughts and language. This reframing can be a powerful tool in empowering patients. Shifting from intimidating terms like "unstable" or "displaced" to patient-friendly language, such as improving muscle coordination or working together to enhance normal movement, contributes to the cognitive aspect of care.

While some of these concepts may already be familiar to you, the exciting development is the growing body of evidence showing the effectiveness of these treatments not just for persistent pain but also for mild or moderate depression and anxiety. The skills and interventions we are already employing in our clinical practice can have a profound impact on addressing behavioral health concerns, offering a comprehensive approach to patient care. It's gratifying to see that the tools we have can contribute significantly to mental well-being beyond the realm of physical symptoms.

Creating safe and healing environments is well within the scope of physical therapy practice. These interventions align with the concept of providing holistic care for individuals with persistent pain. Importantly, everything mentioned falls within the scope of physical therapy practice.

Beyond these physical interventions, cognitive therapy also plays a significant role. Recognizing the interconnectedness of physical and mental well-being, we can provide comprehensive care that addresses both aspects. Integrating cognitive therapy into our approach allows us to contribute to the overall well-being of our patients.

It's important to clarify that advocating for these holistic approaches does not negate the value of medication or other mental health and behavioral health services. These interventions are often crucial, especially for those with moderate to severe symptoms. What we can do as physical therapists is organize our clinical practice in a way that complements and enhances the care provided by mental health professionals, empowering individuals to seek and receive appropriate care.

Considering the severity of the issue is key. For mild cases, a watchful approach that validates feelings, normalizes emotions like sadness and fear, and reassures individuals may be appropriate. Many patients come to our clinics after experiencing life-altering events, and it's normal for them to mourn the loss of function, even if it's temporary.

For more severe cases, introducing the idea of talking to a mental health professional can be valuable. Accessibility to therapy has improved with the availability of telehealth services, and resources like employee assistance programs can offer a few sessions of talk therapy. This resource is often underutilized, and patients may not be aware of the potential benefits it provides. Additionally, various community resources, especially those tailored for specific demographics, may offer discounted or free services. It's essential to be aware of these resources and help patients access them when needed.

I'll share a resource shortly that can assist you in identifying such community resources in your area, especially those focused on supporting families and individuals in various life stages, such as young parenting.

Certainly, there are specific therapies designed for individuals with a history of trauma, such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Prolonged Exposure. It's crucial to highlight that these therapies should only be administered by qualified professionals who have undergone proper training in these modalities. Fortunately, finding such professionals has become more accessible in recent times.

Medication is another option that can be beneficial, although it's essential to emphasize that it's a tool, not a magic fix. Some individuals may find that medication helps balance their brain chemistry, enabling them to engage more effectively in therapeutic work. It's worth noting that for some, long-term medication may be necessary due to specific biochemical imbalances.

However, it's crucial to respect individual autonomy in these decisions. Unless there's a clear danger to the person, forcing medication should not be the approach. In more severe cases, individuals may require more intensive treatment, including hospitalization. While facilitating this process is challenging, it can be a lifesaving intervention.

Low Severity: Conservative Options

For mild depression, identifying symptoms using tools like the PHQ-9 or assessing impairment can guide the approach. Conservative options include pain neuroscience education, movement and exercise, sleep hygiene, dietary adjustments, engaging in enjoyable hobbies, music therapy, purposeful relaxation, meditation, prayer, journaling, and breathing exercises. Recognizing and addressing mild symptoms can be instrumental in preventing the progression of mental health challenges.

Mild-Moderate Mood Disorders

addressing mild to moderate mood disorders requires a delicate balance of therapeutic empathy. While it's natural for empathetic individuals, like many in the physical therapy profession, to immerse themselves in patients' stories, therapeutic empathy involves validating feelings without amplifying or reinforcing symptoms. Personal experiences, such as engaging in talk therapy, can be instrumental in learning how to navigate this balance effectively.

Research suggests that being overly vigilant about low mood can intensify those feelings, similar to how rumination can contribute to increased severity. It's crucial to validate without encouraging hyper-vigilance. Drawing parallels to chronic pain, the notion that occasional sadness is normal but persistent, disabling sadness is not can help patients understand their experiences.

Conservative options, previously mentioned, remain valuable for moderate depression or anxiety. However, if integrated approaches don't yield improvement, it's essential to guide patients toward additional resources. Cultural stigma around mental health requires careful consideration of wording when addressing these topics.

While the focus today isn't extensively on pain neuroscience education (PNE), a notable 2021 study demonstrated its immediate impact on individuals with high PHQ-9 scores. After receiving PNE, their depression scores significantly dropped by an average of 1.35 points. This reduction was particularly notable in the moderate and severe depression groups. While the study's scale is relatively small, it provides intriguing insights into the potential immediate benefits of PNE for those with moderate to severe depression. Continued research will help us understand its broader applications.

Exercise for Depression

Exercise as a treatment for depression has been well-established, and this idea is not new. A notable study from 1999, while older, reinforces the efficacy of exercise in alleviating depressive symptoms. In this study, participants were divided into three groups: one engaged in exercise, another took Zoloft (an antidepressant), and a third combined both approaches. Interestingly, all three groups demonstrated improvement, and there were no statistically significant differences between them. Exercise was found to be equally effective as Zoloft, and the combination of exercise with Zoloft did not enhance effectiveness further.

What's particularly intriguing is that over half, up to 68%, of individuals in each group no longer met the criteria for major depressive disorder as per the DSM-4, which was in use at that time. This indicates a substantial positive impact of exercise on depression. Furthermore, for those with non-remitting depressive disorder in the high-intensity aerobic exercise group, there was a 28% remission rate. This is noteworthy, as it compares favorably to remission rates in medication studies, which often hover around 75% after discontinuation.

Supporting this study, a 2016 meta-analysis examined various studies and affirmed that physical exercise is an effective intervention for depression. It can also serve as an adjunct treatment, reinforcing the notion that exercise is a valuable tool in addressing depressive symptoms. This information underscores the importance of integrating exercise into mental health interventions, considering its notable impact on alleviating depression.

Sleep for Depression: CBT-I

Addressing the significant connection between depression and sleep dysfunction, a study involving 107 participants diagnosed with major depressive disorder and insomnia sheds light on the impact of interventions. The participants were divided into three groups: one received an antidepressant and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia, another underwent CBT plus a placebo, and the third group received the antidepressant along with a four-session sleep hygiene control study.

Interestingly, all groups reported improved sleep after treatment. However, the group that received cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia showed additional improvement in objective sleep measures compared to the sleep hygiene control group. This finding suggests that focused interventions on improving sleep through cognitive-behavioral therapy can be more effective than generic sleep hygiene control sessions.

All groups also demonstrated improvement in depression symptoms, even the group that received a placebo pill without a specific depression-focused treatment component. This implies that better sleep is associated with a decrease in depression symptoms. While causation is not entirely clear and more research is needed, the study highlights the potential impact of improving sleep on managing depression symptoms.

Given that therapists are well-qualified to address sleep-related issues, this study underscores the importance of incorporating sleep-focused interventions into therapeutic approaches for individuals with depression and sleep dysfunction.

Laughter for Depression

Laughing indeed brings about various physiological benefits. It serves as a form of exercise, engaging and toning muscles, while also promoting improved respiration and breathing. Physiologically, better respiration stimulates circulation, leading to a decrease in stress hormones. Since higher stress hormone levels are often correlated with increased depression, this physiological impact of laughter is particularly promising.

Moreover, laughing boosts immune defense, contributing to a lower likelihood of illnesses like the flu. Given the connection between immune function and depression, laughter becomes a valuable tool in supporting individuals with depressive symptoms. Additionally, individuals who laugh more experience an increase in pain threshold and tolerance, along with enhanced mental functioning.

Moving into the psychological realm, laughter has a range of positive effects. It effectively reduces stress, anxiety, and tension, countering depressive symptoms. Furthermore, it elevates mood and self-esteem, addressing key aspects affected by depression. Laughter has also been linked to improvements in memory, creative thinking, and problem-solving skills, all of which can be significantly impacted by depression.

On a social level, laughter plays a vital role in improving interpersonal interactions and relationships, often strained in individuals struggling with depression. It contributes to the building of community, fostering connections and support networks, as mentioned earlier.

An interesting aspect is that laughter is contagious. In social settings, laughter becomes a shared experience, creating a positive, uplifting atmosphere. This social aspect of laughter can be particularly powerful in bringing joy not only to the individual but also to those around them, creating a ripple effect of positivity.

Mood Shifting Exercises for Depression

Exploring unconventional yet effective approaches, mood-shifting exercises have gained attention in the study of mental health. Surprisingly, facial expressions associated with specific moods can influence our emotional states. Studies have indicated that practicing facial expressions linked to particular emotions can indeed shift us towards experiencing those emotions.

Intriguingly, Botox experiments have further emphasized the connection between facial expressions and mood. By selectively paralyzing frown muscles, preventing individuals from using them and allowing only the smile muscles to function, researchers observed a significant 50% decrease in the depression scale for 52% of participants who received the Botox treatment. This outcome is particularly noteworthy as it demonstrates a direct link between facial expressions and emotional well-being.

Additionally, there are specific exercises designed to shift mood, such as assigning individuals to smile at themselves in the mirror for a designated period each day. While the effectiveness of these exercises may partially stem from the amusement of laughing at oneself, research indicates that they have been successful in shifting mood. This unconventional yet promising approach underscores the intricate connection between facial expressions, emotions, and mental well-being.

Exposure Therapy for Anxiety

It's important to acknowledge that exposure therapy for anxiety, especially when related to PTSD, is a specialized intervention that should not be undertaken by physical therapists independently. Exposure therapy involves exposing individuals to stimuli that evoke anxiety with the goal of reducing their fear response. It's important to note that if a patient has PTSD, exposure therapy should only be conducted under the guidance and supervision of a mental health provider.

However, in the realm of physical therapy, a milder form of exposure therapy may be implemented, particularly with patients who exhibit fear or anxiety related to movement. For instance, graded exposure techniques, such as gradually introducing movements that patients are afraid of, can be part of the treatment plan. This may include exercises like nerve glides for patients with low back pain. It's essential to evaluate the severity of anxiety and ensure that any exposure therapy is within the scope of physical therapy practice and appropriate for the individual's condition.

It's crucial to reiterate that exposure therapy for PTSD or non-movement-related anxieties should not be conducted by physical therapists alone. Severe cases may require collaboration with mental health professionals, incorporating a multidisciplinary approach that may involve medications and other therapeutic tools.

Interestingly, advancements in technology, such as virtual reality, are being explored for exposure therapy, often in collaboration with mental health providers. This innovative approach allows for controlled exposure in a virtual environment. Additionally, traditional talk therapy remains a valuable avenue for addressing anxiety.

Cardiovascular Exercise for Anxiety

Numerous studies support the idea that increasing heart rate through regular exercise can have positive effects on mental health, specifically reducing anxiety symptoms. The benefits extend to a decrease in resting heart rate, contributing to overall cardiovascular health. People engaging in regular cardiovascular exercise have reported a notable reduction in sensations associated with panic disorders or panic attacks. Given that these symptoms can be distressing, the potential to alleviate them through exercise is significant.

Moreover, cardiovascular exercise can play a role in reshaping the brain's association between increased heart rate and negative outcomes. For individuals prone to panic attacks, controlled cardiovascular exercise helps the brain uncouple the automatic link between heightened heart rate and danger. This shift in perception is crucial for individuals to recognize that an increased heart rate is a natural response to increased physiological demand, rather than an indication of imminent harm or catastrophe.

While implementing cardiovascular exercise as a therapeutic intervention, it's essential to consider individual tolerance levels. Some individuals may need to start with low-intensity exercises, gradually increasing their resting heart rate by a modest amount, such as 15 to 20 beats per minute. This gradual approach ensures that individuals can acclimate to the physiological changes associated with exercise without overwhelming their system.

Resistance Exercise Training, Breathing and Mindfulness for Anxiety

Resistance training has also demonstrated its efficacy in improving anxiety symptoms, as indicated by a meta-analysis of 16 articles. Notably, individuals engaging in resistance training experienced significant reductions in anxiety symptoms, regardless of whether they had a diagnosed mental or physical illness. While the effect size was slightly smaller for those with diagnosed illnesses, the overall positive impact suggests that resistance training can be a valuable component in managing anxiety. Furthermore, the benefits were consistent across diverse factors such as gender and specific resistance training modalities.

Next, let's consider the profound impact of breathing on our autonomic nervous system and emotions. Breathing is a powerful autonomic function that we can intentionally manipulate to induce changes in our central nervous system. The intricate relationship between breathing patterns and emotions underscores the potential for targeted breathing exercises to influence our mental states.

Attempting to directly control emotions can be challenging, especially for individuals along the spectrum of diagnosed mental health conditions. However, focusing on controlled breathing provides a tangible and accessible method to modulate emotional states. By deliberately adjusting the pace, depth, and rhythm of our breath, we can influence the autonomic nervous system, promoting relaxation and stress reduction.

Understanding the connection between breathing and emotions empowers individuals to leverage this natural and controllable physiological process. Incorporating intentional breathing exercises into daily routines can be a valuable tool for emotional regulation and mental well-being.

However, consider, "What if you approach breathing in this way?" This puts more control in your hands. In the integrated behavioral health framework, empowering patients with control is crucial. Many beneficial outcomes arise from intentional breathing and modifying breathing patterns. Hormonal shifts and neurotransmitter adjustments occur, echoing some effects seen in anxiety and depression medications. Notably, numerous studies advocate for breath work and breathing exercises as primary or supplementary treatments for anxiety.

The same goes for mindfulness. Abundant evidence now demonstrates that mindfulness significantly impacts anxiety and depression. The positive effects of mindfulness directly address symptoms that individuals find most distressing in various behavioral and mental health diagnoses.

Social Interactions

Additionally, positive social interactions play a critical role in behavioral and mental health. It's challenging, especially when dealing with a behavioral or mental health diagnosis, as socializing may be the last thing one desires. Research suggests that the recent decline in social interactions might contribute to increased behavioral health issues. Encouraging any form of social engagement, even a simple walk or sitting at a playground with others around, can make a difference. The interaction with professionals in the clinic also counts as a social interaction – a win.

Loving Kindness Meditation

Moreover, specific types of meditation, such as loving-kindness meditation and compassion meditation, have shown significant benefits for social anxiety. There are many resources for those interested in exploring these practices. You can find numerous examples of loving-kindness meditation and compassion meditation on YouTube. These practices are often used in conjunction with cognitive-behavioral therapy to assist individuals in building tolerance for social interactions. This is a helpful resource you can recommend to patients who may be struggling with the social interaction aspect of their mental health journey.

Altered Breathing

Understanding the mechanics of breathing is crucial in addressing anxiety. When individuals feel anxious, they often exhibit rapid and shallow breathing. This prompts the brain to interpret the situation as a lack of oxygen, triggering a heightened fight or flight response, often accompanied by mouth breathing. Unfortunately, this cycle can become self-perpetuating, leading to increased worry and stress. To interrupt this cycle effectively, a powerful treatment for anxiety involves slowing down the breathing process.

Studies suggest that a simple technique, such as a six-second inhale followed by a six-second exhale, can be remarkably effective. Patients can easily practice this by using the stopwatch feature on their phones, inhaling and exhaling for six seconds each. Just a minute or two of this exercise can help break the cycle of anxiety. Additionally, for those who prefer visual aids or are not inclined towards numbers, GIFs depicting shapes expanding and contracting, found by searching for "anxiety breathing GIFs," can serve as an alternative to guide their breathing and offer a brief respite for the mind.

Anxiety often involves the brain spiraling into worst-case scenarios. Sometimes, the most effective strategy is to temporarily halt this process. Following a GIF, especially one depicting rhythmic shapes, can serve as a valuable tool to redirect attention and momentarily silence the anxious thoughts. This pause allows individuals to bring their brains back online, disrupting the cycle of worry.

Considering the diverse range of options mentioned earlier, certain interventions have demonstrated substantial initial impacts on individuals grappling with anxiety and depression. Key among these are Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE), breathing exercises, biofeedback (utilizing tools like HeartMath), relaxation techniques, meditation, and coping skills. Each of these holds merit in supporting individuals on their journey to better mental health.

Exploring various treatment options demands a tailored, patient-specific strategy. While assessing different interventions, determining the ideal combination for each individual is important. Nevertheless, we need to recognize mental health comorbidities, which our treatments might inadvertently worsen. Screening for these conditions in a patient's history or if currently active and uncontrolled is essential, and can help us to exercise caution when selecting specific treatments.

For instance, if a person is actively dealing with an eating disorder, engaging in cardiovascular exercise might prove more detrimental than advantageous. In such cases, redirecting our focus to breathing exercises or selecting an alternative from the available options on the menu could be more appropriate. In situations where anxiety is present, it's essential to acknowledge that cardiovascular exercise might initially exacerbate the condition before yielding positive effects. Achieving a regulated state is critical for individuals to tolerate such exercise. If their anxiety levels are too high, prioritizing medication to better control symptoms while incorporating breathing exercises and other strategies may be necessary. Once their anxiety is more manageable, we can then explore the proven benefits of cardiovascular exercise.

Remember to be mindful of these considerations. If individuals aren't achieving the desired outcomes, remember the extensive list of options available—think of it as a diverse menu. If one approach isn't proving effective, consider choosing an alternative and revisiting the initial strategy later on. Everyone is unique, and there isn't a one-size-fits-all formula in our line of work. We're not dealing with rigid formulas or chemical equations; we treat diverse human beings with distinct needs and responses.

Incorporating and Merging a Behavioral Health Approach Into Your Current Practice

Let's look at how to seamlessly integrate this into your practice. These symptoms are indicative of trauma. Hypertension and irritable bowel syndrome, for instance, can be manifestations of trauma, particularly in individuals with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and a history of trauma. Some of these items may come as a surprise because we don't always associate them with trauma. It's essential to recognize that it's not a straightforward equation like "everyone with hypertension has a history of trauma." However, the inclusion of this list (see slide 76) serves the purpose of highlighting that if someone aligns with the majority of these indicators, with only a few exceptions, the likelihood of trauma in their history is significantly high. In such cases, it's advisable to proceed with that understanding.

Provide Trauma Informed Care