This course is an edited transcript from the live course, Five Strategies to Help Students with Autism in the Classroom, presented by Tara Warick, MS, OTR/L.Please follow along with your course handout.

Learning Objectives

The participant will be able to identify five strategies to support children with autism in the classroom.

The participant will be able to identify three new visual supports to use in the classroom.

The participant will be able to identify two ways to provide positive reinforcement in the classroom.

The participant will be able to identify three new ways to provide better verbal instruction to students with autism.

The participant will be able to identity the steps of two classroom activities in order to simplify the activity for a student with autism.

Introduction

Today, we're going to begin with reviewing the definition of autism it's characteristics, along with the strengths of those with autism and the challenges they face. We're going to do this by looking at five effective strategies. So first of all, autism spectrum disorder is considered lifelong. There is no current cure for individuals with autism. Many companies are out there that will make these promises, but right now, there are no known cures for autism. There are ways, very effective strategies that we're going to talk about that can teach individuals with autism skills and can help them be very successful, but they will deal with those same types of deficits throughout their life.

Autism Core Areas

The core areas and deficits for children with autism, according to the DSM-5, are separated into two categories. You qualify based on these two categories for having a diagnosis of autism: social communication and adaptive functioning. The way individuals interact with each other, with everybody; and then overall adaptive functioning. Those are the two deficits that we look at when diagnosing individuals with autism. Before, in the previous DSM, the DSM-4, there were three different areas. We looked at social, and we looked at communication separately and then repetitive type behavior. Communication has been made as its own standing area, and they put it into social communication. It's usually evident during the first three years of life. Research is looking at even earlier and earlier than this. There are some studies that are going on here in Oklahoma City, which is where I'm at. They're looking at newborns and looking at how their brains are working when they are babies. The earlier we can diagnose autism the better the prognosis is going to be, because we know the earlier we can intervene and teach them how to communicate and how to interact, the better they're going to be long-term. So it's usually evident during the first three years of life. This is what can make identifying and doing research and working with individuals with autism very challenging. A child may appear to be on the mild side with their challenges. "Mild" meaning their cognitive scores are average to above average, they're very verbal, but they might have just challenges in the social piece. Others may have symptoms that are more severe. Some of those individuals with autism are nonverbal, have a lot of repetitive type behaviors, and a lot of stimulatory behaviors. My favorite quote ever, "if you've seen one child with autism, you've seen one child with autism." Because remembering that these are still kids, these are still individuals and they have their own strengths and weaknesses. What I'm talking about today is just some of those general things you might see in individuals with autism.

Characteristics and Deficits

We're uncertain on the causes of what's causing autism. There's the possibility of multiple-type causes. We do know that there's a genetic influence. We know that if you have one child with autism, you're more likely to have another child with autism or some sort of similar type disability, like maybe a language impairment or a pure social impairment. There's a lot of twin studies on autism that shows the increase in prevalence in twins, and then there's also this two-hit theory, which a lot of research is looking at, looking at individuals possibly being predisposed genetically to having autism. There is also something in the environment that might trigger autism. Think back to what I mentioned earlier about doing research on children and babies with these range of symptoms; it can be very tricky because there's so much going on in our environment, there's so much that can happen during birth, pre-birth, on all these different things that you have to look at to really find out what the cause is of autism.

Prevalence

The prevalence now, it's actually one in 68 children. It's five to one boys to girls. So boys are more likely anyway than girls to have some type of developmental disability. Then when looking at autism, it's five to one, so it's high. It's distributed throughout all the world and all races, nationalities and social classes. It has no boundaries. It's more common than pediatric cancer, diabetes and AIDS combined. So you know, when looking at this, the prevalence now, we talk about this a lot in schools and in our community, that this is not just a situation where the family only needs to know about autism, or the special ed teacher is the only one that needs to know about autism. It really truly takes the village and it takes the community. So it needs to be our neighbors that know how to work with children with autism, or at least how to understand maybe how to be more aware. Our neighbors need to know, families need to know, not just the special ed teacher but the general ed teacher needs to know, the PE teacher needs to know, the bus driver needs to know because this will affect everybody at some level. If it hasn't affected you personally, it will, looking at these prevalence rates. Either personally or professionally, you will know or interact with somebody with autism. I promise you in the near future because it's just becoming more and more common.

Characteristics

Looking at some of those specific characteristics that you might see when you're interacting and working with an individual with autism, the biggest deficit is the social deficit. When I talked in the beginning about the DSM-5, and on the DSM-5, it doesn't say IQ or cognitive, right? Because you can have average to above average intelligence and have autism. It all comes down to the social piece. You might have an individual who prefers to be alone. I have some kids that they seem like they want to be alone, but they really don't know how to interact with anybody. Once I teach them how to approach somebody and interact with somebody, they are more likely to be with others. You might see them having difficulty with relationships. They will sometimes dominate conversations and they only want to do what they want to do, or they have a hard time understanding why they need to also do what someone else wants to do. I have to teach kids how to think about other people besides themselves and think about what other people might like or what other people might want to do. Difficulty understanding the social rules of the school is another one. There's a good chance you could encounter an adult with autism. Children with autism also have difficulty with social rules of the school. I've had a lot of kids get in trouble during this, where they don't know how to watch other kids in the school and do what they're doing and read some of those gray areas in the school. As kids, you change your behavior based on where you're at and who you're with. So many times I'll see kids get in trouble because they act the same way with their peers as they do the principal. If we all acted the same with our peers that we did our principal, we would all get in trouble, right? We have to teach them how to change their behavior based on who you're with and what environments you're in. So understanding those rules can be hard because there's so many gray areas. And individuals with autism can be very black and white, and so we have to teach them how to understand and know those gray areas, those social rules.

Socially naive. We have to be really careful and watch these students to make sure they don't get taken advantage of. For example, I have one boy who was on the school bus and he had a kid tell him if you touch this girl on her breast, then I'll be your best friend. They were thinking they were joking around and the individual with autism was like oh, well, I need a best friend so he tried to do that. He got in trouble of course, and now he's known as this kid who did this to this girl, but he didn't know that he was being taken advantage of. He was just thinking I need a best friend. So understanding what the intentions of other people are can be really difficult for individuals with autism. I had to teach that and we had to break it down and teach some of these social skills like we might teach a math problem.

Imitation. Difficulty imitating the actions of others and learning through observation. We start teaching young individuals with autism the skill of how to imitate. How to watch somebody else and do what they're doing because that's how kids learn. That's how people learn just, in general, is by watching other people and doing what they're doing. If you have an individual who can't do that, they're going to have trouble in school and trouble on the playground and just difficulty knowing what to do. We start this imitation at a really, really young age.

Problem solving. I have 25-year-old who I work with and he does a great job when things are really clear, real black and white. He has got steps that he needs to do. He goes swimming every day in the pool while it's nice out. I was there one day with him and his normal process was: he goes out, he goes swimming and then he goes into the outdoor bathroom, he gets a towel, dries off and then he comes in the house. When I was there this last time, he went outside, he came out of the pool, he went into the bathroom to get a towel and there was no towel there in the bathroom, so he just stood there soaking wet. He had no problem solving skills. He didn't know what to do when things didn't go as planned. I had to teach him how to break those down. If there's a towel there or there's not a towel there, what do I need to do? Getting them to socially interact and asking somebody for help or what to do can be hard, so we have to teach that. We have to teach them those processes.

Organizational skills. Knowing how to organize things and what things are important and not important to keep. Helping them through that process, especially in the school situation can be really hard.

Generalization. The ability to learn something in one environment and be able to do that in another environment can be really hard for individuals with autism. I did a training and we were talking about this with a group of teachers who were struggling because parents said, "Well, they don't do this at home. "At home, they talk and they tell me things." At school, they don't see them talking. The student isn't asking them to do things. So we had to go over this, that many individuals with autism have trouble with generalization, that they will learn a skill in one environment and if you don't teach them that skill in another environment, they're not going to know how to do it. So we have to reteach those things in each environment in order to help them with generalization.

Learning discrepancies. I have some kids who can read really high or decode, I should say. I call it decoding. For example, I had a mom's who's 18 month-2year old kid, could tell mom all the planets, but then they couldn't ask mom for help. So, we had to meet them where they were at in their reading but also looking at in communication. We are going to have to make it simple. We looked at those discrepancies and built on their strengths. We don't want to hold them back in certain areas, that they were really good at, but also made sure we were breaking things down small enough in the areas that were hard for them.

Deficits

Behavioral deficits. I often think these behavioral deficits are what interferes the most with learning. We often view them most when we're thinking about individuals with autism having difficulty with just those changes and those transitions like going from one environment to another environment or one activity to another activity. I've had kids who had difficulty in transition, even when they were going from something they don't like to something that they like. Change can be really hard for them. So, we have to teach that and we have to practice it. What I see happen, on the other side, is I'll hear people say, well, he doesn't like to transition so we just don't transition at all. We have him stay in the same classroom all day. And I say no, we need to think of this as a teaching opportunity because transitions happen all the time, right? I've had about a million transitions already today. We have to know how to transition or we're going be very isolated. So I'll encourage them to practice it all day long.

Becoming easily frustrated. I was working with a little boy the other day and he was trying to write something on a page and he had trouble with his pencil. His pencil broke and even though he had extra pencils there, he just lost it. He got so frustrated because it didn't make sense to him. Why does this have to happen? We had to work through this with him. We worked on how to deal with frustration with a big problem and with a little problem. We're gonna talk about this later, but having that really low tolerance when things don't go the way it's supposed to be. Low motivation to do so because I said so. One of the strategies that we're gonna look at today is reinforcement because you think about the diagnosis of autism and the primary deficit is social skills. Just doing something because you told them to do it because that means you're assuming that they want to make you happy, right? We have to look at if the social is not very motivating to them, then we're going to have to use what is motivating to them. We have to find what it is that gets them going and motivates them and use that to teach them things instead of, in this philosophy that you just need to do it because I said so and I'm the teacher or I'm the therapist or I'm the parent.

Self-monitoring. Self-monitoring is being able to reflect on either their physical appearance, their emotional standing and how they're doing emotionally. Are they tired, hungry? A self-check can be hard for them. For example, a 25-year-old individual who is 25 left his house with stuff all over his face, his shirt on backward. A lot of individuals I work with, they'll just go into the bathroom and they'll leave the door wide open. They have no awareness of what's going on. I did a self-check list for him. So before he leaves the house, he has certain things he needs to do before he leaves. I need to look in the mirror on my face, I need to check my zipper on my pants. I need to do these things before I leave. You also might see some preoccupations with certain items, routines or rituals. So kind of going back to that DSM deficit on there about that adaptive behavior. A lot of individuals with autism will have those almost obsessions over certain things or have special interests that preoccupy them. It might be a behavior like a self stem behavior or it might be an item or it might be a routine or a ritual. I have a young boy who would walk through the apartment complex and he would touch Ford cars a certain way and Chevy cars the other way. That was his ritual and if he didn't do it, his day was completely thrown off.

Nonverbal communication. I don't ever say that kids with autism don't communicate. They communicate even if they're nonverbal, but they might communicate in other ways. They might communicate by bringing you over to get what they want, or they might communicate by throwing themselves out on the floor. They might communicate by biting themselves on the hand. They're communicating through their behavior. You might have somebody who's nonverbal or you might have somebody who has trouble expressing themselves. I have some kids who don't stop talking, they're very verbal, but they don't know how to express their feelings, how they're feeling emotionally. For example, they do know how to express If they're sick or if they're tired.

Asking for help. Asking for help can be a big challenge. So thinking about what we call the theory of mind and its ability to think about somebody besides you. Thinking about how other people are thinking. The core of social skills is thinking about somebody else besides yourself and this can be really hard for individuals with autism. If you think about just simply asking for help, asking for help is saying that I know somebody else might know something more than what I know, which is the theory of mind. An individual with autism doesn't always have a very good theory of mind, so we have to teach that.

Asking for a break. Sometimes individuals with autism do not realize when their body needs a break. So teaching them, when they're starting to get overwhelmed by having a card on their desk and directing their hand to the card to ask for a break. If we don't teach them how to appropriately ask for a break, what are they going to do? They're gonna go back to rocking in my chair and then if that doesn't get him or her a break, he or she is going to start hitting his or her head or the student next to him or her. We have to teach them a way to ask for a break versus waiting for them to escalate and we give them a break.

Understanding verbal directions. Individuals with autism can have difficulty understanding verbal directions. We have to really think about how to keep our directions short and simple and to the point, because that can become very overwhelming for individuals with autism.

Strengths

We have to build on strengths and identify what they're good at, what they enjoy, that's what you have to start with therapy or within the school. So many individuals I work with have a great memory. They memorize things and learn things in ways I would never have thought of such as learning these long routines and directions, I've had individuals who were great at knowing the days of the year. I have this one boy and he was really good at dates. You could say when were you born, or year you were born, and then he could immediately tell me what day of the week I was born on. He was also really good at maps. I could give him my address and he could tell me what day my trash day was. We had to think about how can we start incorporating these things into something for him. There are so many individuals like that who have these crazy strengths that are sitting at home by themselves playing video games because we haven't found a place that would really build on those strengths.

Visual learners. Visual supports helps all of us, right? They help us all function in the world. Thank goodness we have visual supports or we wouldn't know what road to take, we wouldn't know how to bake a cake, we wouldn't know any of those things. It's important for us when evaluating individuals with autism to think about how they can have difficulty processing verbal information and because of that, we're going to have to provide even more visual information.

Black and white thinking. I always say if you really want to know how you look in a pair jeans, you ask an individual with autism and they'll tell you. It's a refreshing way of thinking, they're honest and it's black and white for them. So we have to teach the gray areas. Straightforward, honest and objective, like I was saying.

Topic of interest. When my vacuum breaks, I could YouTube or Google ways to fix it, but if I really have a problem in my vacuum, I want somebody who knows about vacuums. So you take an individual with autism who is interested in vacuums, they are going to learn inside and out of every make and model. Well, thank goodness there are people who have those high special interests that they can focus on and become really good at those areas. I've had individuals with autism, great at computers, maps, arts, and so many different areas that they can focus on and just dedicate everything they do to those special of interests.

Five Strategies

These five strategies are all evidence-based and there's a lot of research behind them. We're going to talk about visual supports, the power of positive reinforcement, task modifications and instructions, social supports, and sensory supports.

Before Implementing Any Strategies

I highly recommend that you as therapist help the teacher look at the environment before looking at any strategies for a classroom situation. I work with teachers on helping them with students with challenging behaviors. I don't start it by just targeting the individual student. I look at the classroom because if you can get more supports in the entire classroom, it will significantly reduce your challenging behaviors. So, we look at the overall environment first before we look at the individual student. In classrooms there's a lot of kids, there's a lot of noises, lights, there's a lot of smells. Teachers use a lot of words, and you know, things change often and quickly. So there's always something different going on. You might have one group going here, one group going there, and there are transitions happening. As mentioned earlier, those transitions are really hard for kids and think about how many transitions are happening in the classroom throughout the day. There is a ton. Other people are not predictable. So especially when you're talking about classmates and other kids their age, that predictability of I know they're going to do this because of this, is difficult. So if a student with autism can't predict their behavior, it can be very stressful for them. So when you walk into that classroom, do you know what is supposed to happen in certain areas? And are there those boundaries? I have one teacher that would go crazy because the students would be around her desk all the time. So we had to provide simple tape around her desk that was off-limits. We said this is staff area, and outside this is student area, you don't cross this line. We had to make it very visually clear what was student area and what was staff area. And do we need to decrease any of the distractions? I'm not saying that the classroom should be like a laboratory. You want your classroom to look pretty and appealing, but you also want to make sure that they can see the important things in the classroom. Can they see the schedule? Can they see what they're supposed to be doing? We recommend all classrooms have at least one break area, especially if you have an individual with autism in your classroom. There needs to be an area where they can go and chill out and relax. A lot of our individuals with autism have trouble with motor planning. You may need to help the teacher looking at their furniture arrangement. Is there a daily routine and schedule posted? A lot of times, when we see more behaviors happening is because there's not a good routine in place. The students don't know what else to do so they have behaviors. We have to teach students the schedule and is the teacher providing notice and warning of changes ahead of time, or are they just thrown on the transitions? Do they have a pretty good routine for when those transitions are happening? I've had some teachers who, they will play certain music during their center times, and then when the music changes, the students know that that means they need to start putting their stuff away. Then when the next song comes on, that means they need to go to the next center. So she's just found a way to build in that transition with music and it worked really well for her students. In the handout section, you will see a classroom management checklist. So this would be something not necessarily that you would go in and just do it with the teacher. It would be more of a resource that you could provide to teachers or even administration on what to think about in the classroom.

Figure 1. Classroom management schedule.

There are different activities on here, so Figure 1 is targeted probably more towards your elementary age kids, but it's a great one just to kind of walk-through with teachers.

Visual Supports

Now we are going to get into visual support. We've looked at the classroom, we've helped the teacher with the environmental arrangement so now we're gonna get into the strategies. The first one that we're going to look at is visual supports. So visual supports, as we talked about earlier, thinking about how auditory information for individuals with autism can just come and go really easily. It doesn't stick. With a visual support, it sticks. It's static. Some examples that you might see, and or you might have used before like environmental cues. For example, a sign that has where the gym is or where the restroom is.

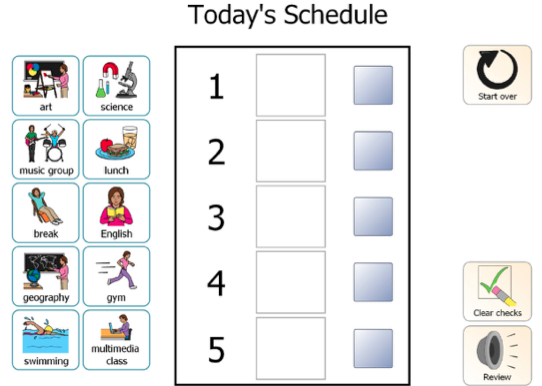

Calendar schedules. I'm gonna show you a bunch of examples of these. And if you have individuals with autism in the classroom, they need a schedule, they need a calendar. They need to know what is on their schedule for the day, what's coming up. Figure 2 is an example of a calendar schedule.

Figure 2. Calendar Schedule.

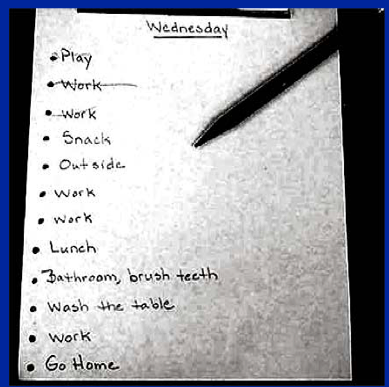

Checklists. I use checklists (Figure 3) a lot for individuals with autism because they can have trouble with multistep activities. So using a checklist can help with those multistep activities. Even if it's an activity that's like you just need that when you're finished with your work, you need to find something to do, that can be overwhelming for them. So I might do a checklist that just says when I'm done with my worksheet, and I have a list, I give it to my teacher, I go find a book to read, I come sit back down. So they can go through that checklist on their own. The purpose really of these visuals is to help decrease the need for somebody else to be there and help teach individuals with autism to be more independent.

Figure 3. Checklist.

Timers. Another great tool (Figure 4.) if you have an activity that has a time limit on it, you can use timers to show them when that activity is going to be over, when a transition is going to happen.

Figure 4. Timers.

Teacher/student signals. I've had teachers use these before with very good success, where we had a student who would get overwhelmed in the class and wasn't able in the moment and didn't necessarily want to raise his hand and say I need a break, Mrs. Smith. So they came up with a little hand gesture that they used and it could go either way. So if the teacher saw the child getting stressed, she would give him the signal. If the student felt like he was getting stressed, he could give her the signal. So when he did that, the teacher would just come up with something. If they gave each other the signal, the teacher would then say Johnny, could you please take this note down to the office for me? So it was a way to get him out of the classroom for a break without having the behaviors and not having to, in front of everybody, talk about I need a break or I need to leave. So it was really subtle and it worked well for this team.

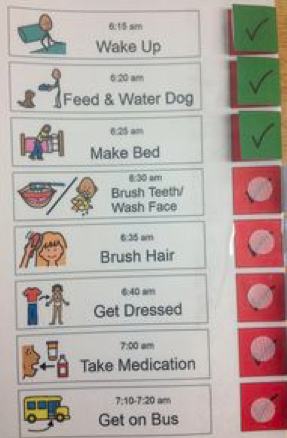

Mini schedules. A mini schedule breaks down schedules even more, maybe just washing hands or play or, like I was saying early, maybe just what to do when I'm done with my work. So those would be more mini schedules of an activity in the day. So the purpose, as I said, is to clarify those expectations. This is a great visual for home situations. Figure 5 shows what a student would do before they got on the bus, because once again, even this is another transition, getting dressed in the morning or getting ready to go to school in the morning can be really hard for some kids. This helps parents with a strategy. We are going to wake up, feed and water the dogs, make the bed, and as they do that, they get to put a checkmark on the list. It. takes those power struggles off and it puts it on the visual. So they can see what all they need to do in the morning, and it teaches them independence.

Figure 5. Mini schedule.

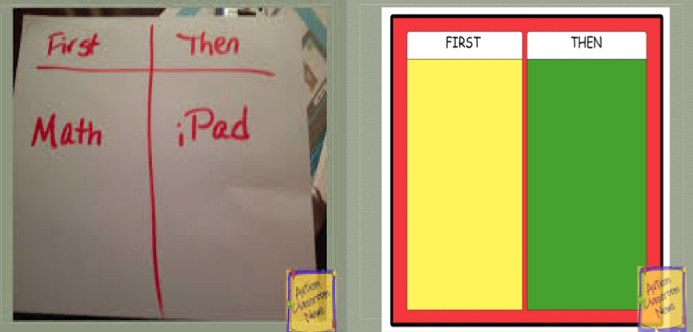

First and then. I will do this even with kids who are very verbal and when you do this, you also use simple instruction. So if I didn't have this, I might be saying okay, I need you to go ahead and do your math, and then after you finish your math and you turn it in, then you can play on the iPad for a few minutes. You need to do your math first before I give you your iPad. I used a lot of words right there. If I have it in visual and I have it written (Figure 6), I can say simply point to it and say first math, then iPad. It makes my language really simple, short, to the point, and it gives them that visual reference to keep, versus me saying it. It's a way to kind of categorize your problems or things that are stressing you out in a visual way.

Figure 6. First and then chart.

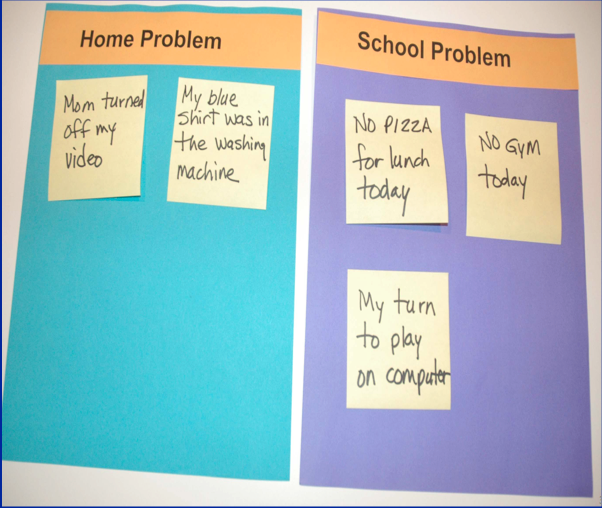

Home problem vs. School Problem. Kids with autism have these rituals, routines, and so every morning I eat cereal in my blue bowl, I eat my Froot Loops with this and this. If you have a day didn't happen, the kid could get really stressed out. The chart in Figure 7 can be used to teach them a way to categorize their problems. That was a home problem, we are at school now and these are school problems. So that can help just relieve their stress a little bit.

Figure 7. Home vs. school chart.

Figure 8. Activity Chart.

The activity chart in Figure 8 is a visual that we've used before in circle time to where it can show them what's supposed to happen and what happens when the activity is over. So in this example, you'll see that they were reading Brown Bear, Brown Bear. As they went through the pages, they would take off those visuals. When they were all taken off, that meant the book was over and it also gave them a way to participate. So maybe if they couldn't say the words, the different animals, they could give the picture when it was that page on the book. A lot of our individual students with autism have trouble during these times that are less structured such as, like your home living, your centers, kind of more those open play type activities. So this is a perfect example of how to break things down and use those mini task lists.

Playing with toys. Figure 9 is a play routine on how to wash dishes. So I turn on the water and it gives you a list of how to do this. Now in my tips under visuals, you have to teach this. So just me putting this out on a sink is not going to work. The students are not all of a sudden know how to wash their hands or use a play sink, right? We're going to have to teach those. I work with a preschool program here in Oklahoma City. It's a research study and it is looking at providing kids with ABA, a certain amount of time, which is applied behavior analysis. So it directs teaching, but it also looks at inclusion. It's looking at teaching kids and peers and how to be a part of a group. I was there yesterday with this group of teachers. I was working with them and we were observing. It was so interesting because the students were doing really well. They said we had to teach them these play skills because like one of the kids they have given us an example of, whenever he first started, he would take any toy, he would run from toy to toy around the classroom and just tap his teeth on it. They had to think, oh he's tapping because he doesn't know how to play. So they had to breakdown each toy and teach them how to play. I would have never guessed that when I was watching him in the classroom yesterday because he was just standing at a table and he'd go from one toy to the next just playing. So he'd play for a little bit, move to the next toy, play with it a little bit. So it was really neat to see that and how important it really is to break these skills down and teach them how to play. He was able to play with those toys, he was able to be with his peers. The other kids were doing shape sorters, one kid was doing puzzles, and so and then they would just rotate around the table and he was rotating with his peers because he learned how to play with toys.