Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify three benefits that cancer survivors derive from participating in an exercise training program

- Correctly interpret the physiologic changes which occur during an acute exercise bout

- Associate adaptive changes to participation in an exercise training program with an improved functional capacity

- Safely perform an exercise test

- Write an exercise prescription based on estimated heart rate max and/or results from an exercise test

Introduction and Overview

Twenty years ago, no one was interested in the topic of exercise in the oncology setting. Today the interest is overwhelming and with good reason. Generally, patients enter treatment in poor condition, and that condition typically worsens as they proceed through treatment. Emerging evidence clearly indicates that cancer survivors can derive a number of physical and psychological benefits from participating in an exercise training program. Participation in an exercise training program can reduce symptom burden and improve the quality of life in the cancer survivor. Note the key term "symptom burden". These survivors already face a significant symptom burden; we can help lessen it by getting them into the gym to exercise.

I'd like to remind everyone that our systems (cardiovascular, pulmonary, muscular, and vascular) are in a dynamic equilibrium between supporting normal physiologic function. In other words, they are adequately meeting the needs for aerobic conditioning and muscle strength, which is the optimal condition. However, under the most extreme conditions, physiologic dysfunction (or what you and I would normally call de-conditioning) can occur, and this reflects a decline in normal physiologic function.

VO2

A key point to my comments today involves the linkage between increasing treadmill speed, and a construct called VO2 peak or VO2 max. VO2 is the amount of oxygen that is consumed to meet a particular exertional level. Assuming that everyone participating in this webinar is seated right now, we are consuming about 3.5 mLs of O2 per minute per kilogram of body weight. The next breath you take in will have about 21% O2; the next breath of air you exhale will have only about 19% O2. That 2% difference has been used to fuel ongoing biological processes. If I were to put anyone on a treadmill and progressively increase the speed of that treadmill, one would see that his or her oxygen consumption would progressively and linearly increase with increases in treadmill speed, reaching a peak VO2. This is the maximal amount of oxygen that your body can consume, and obviously, that value will dictate the maximum treadmill speed that you can obtain on the treadmill. One of the benefits of exercise training is that one can increase his or her VO2 max by about 20%, depending on where you start an exercise training program. What that means is at a given treadmill speed, with conditioning, one can meet that demand more efficiently, more effectively.

Heart Rate and Treadmill Speed

A second construct I need to bring to your attention is the relationship between heart rate and treadmill speed. Again, it should come as no surprise to anyone in the audience that with increasing treadmill speed, heart rate increases. This is exactly why monitoring heart rate is so vitally important in any exercise setting because it provides immediate physiologic insight into the status of the patient. Again, there is a linear relationship between heart rate and treadmill speed. With training, it takes a greater treadmill speed to achieve that same particular heart rate. This is why, one of my take-home messages from today's comments is that for all of your patients engaged in an exercise program, monitoring heart rate in real time is vital and essential. Put a heart rate monitor on the patient before they even get onto the gym floor.

Oxygen Consumption and Our Patients

Why am I making comments about a physiologic construct? In point of fact, that physiologic construct describes a couple of things that we have all learned in PT school. Completion of ADLs requires an oxygen consumption of between 10.5 and 17.5 mLs of oxygen per kilogram, per minute. The VA says that if you cannot reach a VO2 max of 17.5 mLs, then you are suffering from a disability.

In a particular study that looked at the energy cost for doing ADLs, the energy cost of doing the ADLs was compared against the peak VO2s of individuals who were healthy and normal. The individuals that were healthy and otherwise normal had a peak VO2 of 27 mLs per kg. The individuals that were ill (they had suffered from a stroke) had a peak VO2 between 10.5 and 17.5 mLs of O2 per kilogram minute (Ivey et al., 2005). To complete any of the ADLs for a healthy normal, they had more than an abundance of oxygen to meet the energy demands of standing up, brushing their teeth, etc. In contrast, the patients that were recovering from strokes and had this range in their peak VO2s, the energy costs of performing those ADLs, equaled if not exceeded their peak ability to utilize O2. In other words, for individuals that were stroke survivors, they didn't have the energy reserves to meet the energy costs of doing their ADLs. For example, they couldn't wash their hair, which was the most energetically expensive ADL performed by anyone. We intuitively know this because we've all been taught energy conservation techniques at some point in our PT education. The whole notion behind energy conservation is to better match the energy cost of the activity with our ability to utilize that energy. Carrying small packages and making multiple trips requires a smaller amount of one's individual peak VO2 and makes it a less physiologically demanding activity. The whole notion of energy conservation is to better match our actual ability to utilize O2 and the energy costs of what we're trying to perform. That's the importance of understanding the utilization of O2.

Muscle Strength

In discussing peak VO2, we're talking about aerobic capacity. Everyone has been asked by a healthcare provider to retrain an individual. Oftentimes, they're speaking primarily about aerobic capacity, peak VO2s. Additionally, we're often asked to recondition patients in terms of their muscle strength. This is a key component of an overall and complete exercise program for the cancer survivor. As I'll point out later, the key assessment tool for assessment strength is a determination of the 1-RM, or the so-called "one rep max". This is a standard across almost all settings. I would also like to remind everyone that strength training is functional, as well as fundamental. Today, I would like everyone to take away the notion that it's not aerobic training or strength training, but rather it is aerobic training and strength training together. This is particularly true for the cancer survivor for many reasons which we will outline shortly.

Strength and Function

Very briefly, I would like to look at some data from Amy Litterini (2013). She pointed out that measures of strength relate to functional capacity. In this particular study, she measured strength, one rep maxes, and she correlated that with measures that you and I recognize as being assessments of function, including repeated chair stands, gait speed, and balance speed. For now, let's just focus on chair stands. For individuals that underwent a 10-week resistance training program, they were able to increase the number of chair stands that they performed by a functional and clinically significant amount. As it turned out, this increase was also statistically significant.

I straddle two worlds: the exercise world and the PT world. Sometimes it's challenging. What PTs measure as function is predicated on what exercise physiologists perceive as strength and aerobic capacity, VO2 max. They're not independent of one another; they're dependent on one another. Hopefully, that helps you understand the notion of function and exercise training.

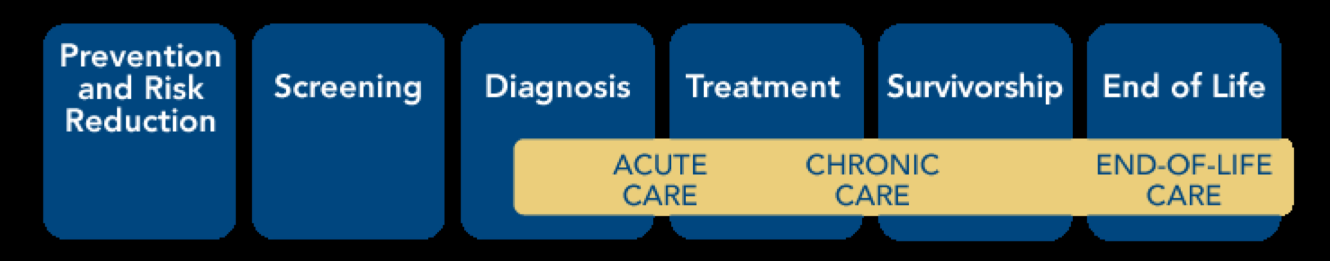

The Cancer Continuum

I would like to remind everyone that cancer is viewed on a continuum (Figure 1). There is a role for a physical therapist at almost every level in this cancer continuum.

Figure 1. Cancer continuum.

First, an individual can be an oncologic physical therapist and not even see patients with cancer. If one is interested in providing community health services, exercise training programs, and weight loss programs, one will be actively engaged in preventing and reducing the risk for developing several cancers, including prostate, colorectal, and breast cancers. One can lessen their risk for developing these particular types of tumors by engaging in exercise training.

Once a cancer is diagnosed, many times in the cancer continuum there is a period of time where maybe chemotherapy is provided in a new, adjuvant manner, before surgery or radiation has begun. This a perfect time when cancer patients can be introduced to physical therapy and be introduced to training exercise and strength training. There are limited data that suggest that providing exercise training during active treatment can reduce the adverse effects of the treatment, and in some cases, it may even improve the efficacy of the chemotherapeutic agent themselves.

We can all appreciate the fact that getting cancer survivors to exercise while receiving treatment is very challenging. Even if they do very little, that is better than doing nothing. Furthermore, at this point in the cancer continuum, minimizing loss may become the primary goal as opposed to making an improvement. Once a person reaches the survivorship stage, they need to be returned to their normal level of physiologic function. As such, during survivorship, participation in exercise training becomes important.

Lastly, PTs belong in palliative care. Patients in palliative care typically want to be able to sit up in a chair to greet their visitors. There are many things that we can do with patients at the end of life that involve fundamental PT services, strengthening, and aerobic conditioning, making it possible for these patients to transfer to a bedside chair, and to stay upright in a chair long enough to meet and greet their visitors. PT has a role along this entire continuum.

Importance of Exercise in Oncology Diagnosis/History

Why is exercise an important topic in the context of oncology diagnosis and history? According to the Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report (2013), many Americans fail to meet the minimum aerobic and muscle-strengthening guidelines, which include 150 minutes of moderate, aerobic exertion per week and two visits to the weight room, combined with flexibility training. Adults in the U.S. meeting both aerobic and muscle-strengthening guidelines are as follows:

- > 25% of the population (2 States)

- 20-25% of the population (27 States)

- 15-25% of the population (18 States)

- < 15% of the population (3 States)

As evidenced by these statistics, Americans are poorly trained and do not meet minimum exercise guidelines.

If the healthy population doesn't meet these guidelines, it should be reasonable to assume that neither do cancer survivors. In 2013, Mason and colleagues looked at the percentage of breast cancer survivors that met aerobic activity recommendations. Their team found that one year prior to diagnosis, 30% of patients met minimum standards. Additionally, 30% of survivors met those standards 24 months' post-treatment. At five years' post-treatment, upwards of 40% of these patients did meet guidelines, but 10 years' post, less than one in four of these breast cancer survivors met these minimum guidelines. There is very convincing data to show that participating in exercise training reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence by upwards of 50%.

I want to come back to this notion of aerobic capacity. Lee Jones and his group at Duke conducted a study that compared the peak oxygen consumption of age-matched healthy individuals with breast cancer survivors (Jones et al., 2012). Before treatment, there was about a 31% difference between the healthy individual and the breast cancer survivor. During treatment, as you might expect, peak VO2s to climb, but again, the difference between age-matched healthy individuals and the survivors is about one third (31%). After the completion of active treatment, peak VO2s remain depressed in the breast cancer survivor. In individuals who have metastatic disease, again, peak VO2s are substantially lower than they are in healthy individuals. In other words, even after completion of treatment, breast cancer survivors (as well as several other diagnostic groups) simply do not recover their age-matched and expected peak oxygen consumptions.