Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Interdisciplinary Approach To Stroke Rehabilitation: Acute Care And Inpatient Rehabilitation Phase, presented by Alaena McCool, MS, OTR/L, CPAM, Katherine George, PT, DPT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Examine 3 appropriate assessments to use during an acute care OT and PT evaluation based on the patient’s diagnosis.

- Analyze at least 3 appropriate interventions during the inpatient rehabilitation phase based on the patient's diagnosis and presentation of symptoms.

- Recognize the importance of the interdisciplinary approach between physical and occupational therapy and discuss how to implement collaboration strategies during case studies.

Content/Introduction

- Disclosures

- Introduction

- Stroke Overview

- Case Study Introduction

- Acute Care Rehabilitation

- Inpatient Rehabilitation

- Literature Update

- Case Studies

- Questions and Answers

Today, we will discuss an overview of stroke, including the definitions and medical management, and review interdisciplinary approaches to stroke rehab in acute and inpatient phases. We will also apply case studies throughout the presentation.

Why are we here talking about an interdisciplinary approach? When professionals from multiple disciplines come together to create a care plan for a patient, each professional has a slightly different perspective based on their specialty, which can help create a more comprehensive care plan and optimize patients' recovery. From a patient's perspective, their care plan is more consistent and harmonious.

A massive amount of literature also discusses why early mobility is better for all types of patients, including those post-stroke. Early mobility is generally safe and effective in promoting better outcomes, shortened lengths of stay, and improved functional mobility. For example, disciplines can split up mobility tasks where OT is working on bed-level ADLs and transferring them to the chair so that the PT can work on standing and walking. They can also work together for evaluations and treatments utilizing two skilled sets of hands. In this way, they can focus on the client's quality of movement, which is very important in the neurological population.

Many populations benefit from energy conservation, including stroke patients, especially in acute cases. Combining PT and OT in one session may sometimes be all that a patient can tolerate.

From a time management perspective, clearing a patient for other disciplines saves time and money. Communicating a patient's response to your session can help another therapist prepare, saving time.

Stroke Definitions

- Ischemic Stroke (87% of strokes)

- Obstruction in cerebral vasculature prevents brain tissue from getting oxygen and nutrients, causing cell death.

- Hemorrhagic Stroke (13% of strokes)

- Blood vessel rupture or leakage causes blood to flow into brain tissue

(Tsao et al., 2022)

Let's review some definitions so we are all on the same page here. Ischemic strokes are due to an obstruction in the vasculature preventing the brain tissue from getting oxygen and nutrients. These obstructions can include blood clots or fatty buildup.

Hemorrhagic strokes are due to blood vessel rupture or leakage causing blood flow into the brain tissue, which causes cell death. This can be due to aneurysms or weakness in the vessel wall, uncontrolled hypertension, and the overuse of medications like anticoagulants. Eighty-seven percent of all strokes are ischemic, and 13% are hemorrhagic. Hemorrhagic strokes are more severe and have worse outcomes than ischemic ones.

Common Presentations

Here are some common presentations in this chart.

Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA) | •Branches from the basilar artery •Supplies occipital and temporal lobes, thalamus | •Visual deficits •Contralateral strength and sensory loss •Aphasia with L PCA strokes •Neglect with R PCA strokes |

Vertebral Arteries/ Basilar Artery | •Vertebral arteries join to form the basilar artery •Supplies the posterior portion of the brain, including the cerebellum and brainstem | •Vertigo, visual deficits, speech deficits, balance and coordination deficits, including ataxia with cerebellar strokes •Strength, sensation, vision, swallowing, breathing, and arousal deficits with brain stem strokes |

| Middle Cerebral Artery (MCA) | •Largest vessel branching from the internal carotid artery • Supplying large areas of the frontal/temporal/ parietal lobes and basal ganglia | •Contralateral strength and sensory loss in face/arms > legs •Contralateral homonymous hemianopia •Aphasia with L sided MCA strokes •Neglect with R sided MCA strokes |

| Anterior Cerebral Artery (ACA) | •Branching from the internal carotid artery •Supplies portions of the frontal and parietal lobes | •Contralateral strength and sensory loss in legs > arms •Confusion, delayed response times, memory deficits •Apraxia possible |

Most clinical presentations do not fit into a nice little box as with all neurological conditions. It is nice to have basic knowledge about what to expect to help guide your evaluation process and decision-making. This is a general overview of what you should have in your head when you complete a chart review.

Next, we will go over the stages of stroke, including more definitions for your reference.

Stages of Stroke

- Hyperacute: 0-24 hours

- Acute: 1-7 days

- Early Subacute: 7 days-3 months

- Late Subacute: 4-6 months

- Chronic: 6 months+

We will mainly address the hyperacute, acute, and early sub-acute phases during today's presentation.

Stroke Quick Facts

- “Leading cause of serious long-term disability”

- Global Incidence: 11.71 million people

- U.S. Incidence: ~ 795,000 people

(Tsao, 2022)

Stroke is the leading cause of serious long-term disability. The incidence rates of strokes in the US and globally are very high, and one in four stroke survivors will have another stroke in their lifetime. Those with recurrent strokes tend to have higher mortality rates and worse functional outcomes.

- Readmission Rates (Leppert et al., 2020)

- 12-17% readmitted within first 30 days

- Up to 50% readmitted within 1 year

- Rehab Needs (Almhdawi et al., 2016; Leppert et al., 2020)

- Two-thirds of all stroke survivors need rehabilitation

- More than 80% present with UE deficits and/or gait deficits

Up to 17% of stroke survivors are readmitted within the first 30 days, and up to 50% within one year. There are many different reasons for these readmissions, including falls, fractures, recurrent strokes, and other medical complications. Two-thirds of all stroke survivors need rehab, and more than 80% end up with upper extremity and/or gait deficits.

Introduction to Case Study J.K.

- J.K. is a 67-year-old female presenting after an unwitnessed fall with acute right MCA stroke, left shoulder hematoma, left 4th rib fracture, and left pneumothorax

This is an introduction to J.K. We will follow J.K. throughout her recovery, which spans parts one and two of this course series.

She is a 67-year-old female presenting after an unwitnessed fall with an acute right MCA ischemic stroke. She has a left shoulder hematoma, a left fourth rib fracture, and a left pneumothorax.

Acute Care Rehabilitation

Acute Care Overview

- Care Team

- Physicians

- Nurses

- Respiratory Therapists

- Case Manager/Social Worker

- Rehabilitation Services

- Dietician

- Patient and Family Members

- Pharmacists

- Palliative Care Specialist

- Stroke Recovery Group Liaison

Many professionals are involved in the care of a patient after a stroke, and these can vary by facility.

Ischemic Stroke Management

- Revascularization

- Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator (IV-tPA)

- Endovascular Thrombectomy (EVT)

- Blood Pressure Management

- Cerebral Edema/Intracranial Pressure Management

Medical teams will focus on revascularization for an acute ischemic stroke using IV-tPA or intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. It can be used within three to four-and-a-half hours of the patient's last known normal. They also provide endovascular procedures such as thrombectomies, which is the removal of a thrombus, or thrombolysis, which is the delivery of TPA directly to the clot. These procedures can be performed up to 24 hours after the last known normal.

Medical professionals also manage blood pressure after an ischemic stroke, as they need to be high for adequate perfusion. Blood pressure goals can be less than or equal to 220 over 120 within the first 24 to 48 hours.

Cerebral edema management and intracranial pressure management are also used with this population, as there is an increased risk for cerebral edema after a hemispheric infarct. Surgical interventions, such as placing an external ventricular drain or a decompressive craniectomy in severe cases, can be used.

Additional medical management is going to include the prevention of complications in recurrent stroke during hospitalization using diagnostic imaging, seizure prophylaxis, and encouraging early mobility.

- Therapy Implications

- Therapy holds post IV-tPA and EVT

- Blood pressure goals

- Surgical precautions

- External ventricular drain precautions

Therapy implications with ischemic strokes include therapy holds after tPA for 24 hours and after endovascular procedures are common. They use the femoral artery to access the vasculature system resulting in "lie flat" orders. The time for a therapy hold after the different endovascular procedures depends on your facility.

Monitoring blood pressure during sessions is essential. If blood pressure goes too high, we can cause another stroke or hemorrhagic transformation of their current stroke. If blood pressure is too low, there may not be enough pressure for perfusion to the brain. Blood pressure goals are not universal, and many factors go into making them. We always want to defer to our medical team. As therapists, we need to ensure that we get individualized blood pressure goals to manage them appropriately during our sessions. When blood pressure goals are high, as we would expect with an ischemic stroke, we need to use our clinical judgment regarding the appropriateness of therapy. Just because the doctors have set a blood pressure goal to keep systolic pressures between 180 and 220 does not necessarily mean that it is appropriate to work with a patient with a resting blood pressure of 210 over 105, as blood pressure increases with activities. Discuss with the medical team to weigh the risks and benefits of early mobility in the acute phase with these patients.

Surgical precautions are going to include helmets for craniotomies. Additional precautions will depend on the facility and the surgeon performing the procedures.

An external ventricular drain (EVD) is a tool that can be used to measure intracranial pressures and drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or blood to lower intracranial pressures if needed. When the drain is open and actively draining CSF or blood, mobilization is contraindicated. The EVD must be clamped for mobility.

Hemorrhagic Stroke Management

- Control Bleeding

- Intracranial Pressure Management

- Surgical Intervention

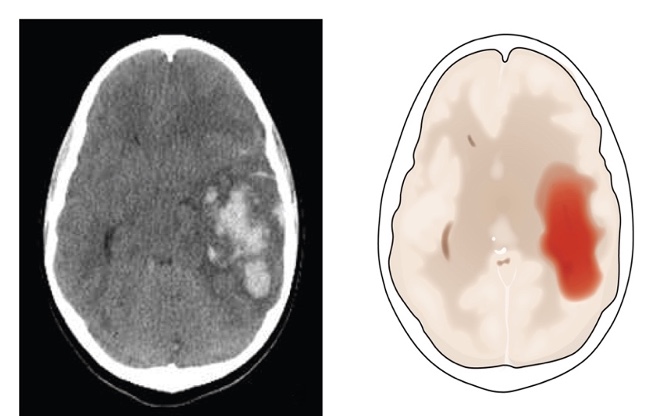

For acute hemorrhagic strokes, the medical team is going to work on controlling bleeding and preventing hemorrhagic expansion with blood pressure management and the use of medications, platelets, or fresh frozen plasma. Figure 1 shows an example of a hemorrhagic stroke.

Figure 1. Examples of a hemorrhagic stroke on a scan.

There are typically strict blood pressure goals for these patients to prevent further bleeding. There are systolic goals of around 130 to 140.

Using EVDs or external ventricular drains to monitor and manage intracranial pressures after hemorrhagic strokes is associated with improved survival. You will see many patients with EVDs in neurologic ICUs.

There are surgical interventions to remove blood in the brain tissues and minimally invasive options such as burr holes. More invasive procedures, such as craniotomies and craniotomies, can be used depending on how much blood and where the blood is.

Additional medical management here will be the same for ischemic stroke and will include the prevention of complications and recurrent stroke during their hospital stay.

- Therapy Implications

- Blood pressure goals

- Surgical precautions

- External ventricular drain precautions

Therapy implications for a hemorrhagic stroke related to these medical procedures will include individualized blood pressure goals and constant blood pressure monitoring during sessions. Reduced blood pressure variability after hemorrhagic stroke has been shown to increase functional outcomes. We want to take extra precautions with this patient and keep their blood pressure within those recommended goals so as not to increase the risk of further bleeding.

Surgical precautions are similar to those for ischemic strokes, including using a helmet after craniotomies. Therapy holds will depend on the procedures that are being done.

Again, external ventricular drains must be clamped for mobility.

Acute Care Evaluation

- Medical Chart Review

- Patient Interview

- Objective Assessments

- Goal/Plan of Care

- Equipment/Orthotic Recommendations

- Discharge Planning

Alaena: We will discuss these topics for the acute care evaluation.

- Chart review

- Hospital Guidelines

- Lines and Tubes

- Diagnostic Imaging

- Past Medical History

- Hospital Course

- Precautions

The chart review starts with knowing your hospital guidelines, policies, and procedures. Guidelines can include the vital lab levels, vent settings, and when it is appropriate for us to go in and see the patient. Even if the labs are showing therapeutic, it is always important to talk to the nursing team to see if they are appropriate for therapy.

From the chart review, we will see the types of lines and tubes the patient has to better manage those. For example, if we know the patient has an EVD, we should check with nursing to see how their intracranial pressures are and if they can have the EVD clamped for treatment.

Diagnostic imaging includes x-rays, ultrasounds, MRIs, or CT scans. Due to the complexity of this population, sometimes things are missed by the medical team. For example, you may look at an x-ray and notice a potential scapular fracture. We need to reach out to the medical team to express our concerns. Our job is to not provide any more harm to this patient and to get them better.

The next one we will look at is past medical history like high blood pressure, strokes, surgeries, medical complexities, pain and pain tolerance, medications, and so on.

Lastly, we should know their precautions. Precautions can be specific to the surgeon if the patient has had surgery, but typically in this population, we will see the precautions that Katie previously discussed. If a patient receives tPA, they cannot participate in therapy for 24 hours post-thrombectomy, and there will be a lying flat order. Blood pressure parameters try to keep systolic below 140 to 160; however, this range may depend on a patient's medical history.

- Patient interview

- Include Family

- Home Setup

- Cognitive Assessment

- Prior Function Level

- Pain

The subjective patient interview should include family. You may ask the patient some questions, and family members can confirm that it is accurate. If the patient cannot provide information because of communication or cognitive issues, the family can provide that. If family members are not in the room, you go back into their chart post-session and try to contact the emergency contact number. If you still cannot contact them, the next step would be to reach out to a case manager to see if they have any information about the family.

The reason we want to do this is to confirm everything the patient is saying and have an accurate history of what the patient was doing before having the stroke. During this patient interview, we can learn about the home setup, including accessibility, like if there are any stairs to enter the house. We also want to determine family support.

Cognitive assessments can include informal questions like orientation and following commands or formal ones like the MOCA. We can also have the patient track objects in the room to see if there are any visual processing things going on. If at any time when doing these assessments, you suspect cognitive or communication deficits, a speech pathology referral may be indicated.

Prior level of functioning will include their ability to perform ADLs and IADLs, mobility, work, and leisure activities before the stroke.

Finally, if they are having pain or have a low pain tolerance, we can coordinate with nursing to have pain medication administered before our session.

Outcome Measures

Objective assessments will include range of motion, strength, ADLs, and mobility. However, the two lists show discipline-specific measures. We are not going to go through all of these, nor is this an exhaustive list of the assessments available. The assessments with the asterisks are highly recommended by StrokEDGE, Stroke Evidence Database to Guide Effectiveness, a template for measuring effectiveness and quality of evidence for outcome measures.

- Outcome Measures: OT

- Action Research Arm Test

- Box and Blocks Test

- Clock Drawing Test

- Modified Ashworth Scale

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- Motricity Index

- NIH Stroke Scale

- Orpington Prognostic Scale*

- Star Cancellation Test

- Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement*

- Outcome Measures: PT

- 5 Times Sit-to-Stand*

- 6-Minute Walk Test*

- 10–Meter Walk Test*

- Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale*

- Berg Balance Scale*

- Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment

- Functional Gait Assessment

- Motricity Index

- NIH Stroke Scale

- Orpington Prognostic Scale*

- Postural Assessment Scale for Stroke Patients*

- Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement*

- Trunk Impairment Scale

https://www.neuropt.org/practice-resources/neurology-section-outcome-measures-recommendations/stroke

Above are the OT and PT lists. Again, we are not going to go through all of these, but rather we left these lists for your reference. The ones with the asterisks at the end are recommended through StrokEDGE and are the most up-to-date recent clinical practice guidelines.

Specialized Assessments

- Arousal

- Tone/Spasticity

- Sensation

- Coordination

- Visual Assessment

- Neglect/Inattention

- Sensory vs. motor vs. visual

- Cognition

Along with the OT and PT assessments, we are also going to look at other ones that are available specific to the stroke population to give a more accurate and thorough picture of the patient and capture what deficits are impairing their independence, ADLs, and mobility.

The first one up is for arousal. There are multiple assessments, with the more common one for acute care called the Glassgow Coma Scale or GCS. This is appropriate for a client with a low-level stroke and a way to show progress.

The next specialty assessment is for tone, and most likely, you will see PTs and OTs using something called the Modified Ashworth Scale. There is an upper and a lower extremity portion, and observations for synergistic patterns, clonus, and fixed posturing if noted. It is important to note that when you see anything out of the norm or these patterns, the focus should be on what impacts function.

For sensation, we look at proprioception, sharp/dull, discrimination, light touch, temperature, and stereognosis. Stereognosis is typically seen in lesions of the sensory cortex of the parietal lobe. Intact sensation is important for both function and safety. For example, if their sharp/dull discrimination is not intact when mobilizing, they can hurt themselves if they bump into something.

Coordination assessments can include testing for dysmetria, ataxia, tremors, and other movement disorders.

Visual assessments include visual acuity, an easy assessment to perform at the bedside. A therapist can have the client identify colors and numbers from items in the room, like a clock. Smooth pursuits, convergence, saccades, peripheral vision, and field testing can be tested by following a therapist's finger. Neglect and inattention can result from sensory, motor, and visual issues.

Cognitive assessment includes tools like the MOCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), which can be assessed during ADLs or dual tasking during PT. It is important throughout all these that you collaborate with your counterpart. One discipline may see something, while the other may not. Depending on the time of day, a client may mask deficits easily, especially using different medications. By collaborating with your counterpart, you are going to obtain a fuller picture of the patient and be able to make the most appropriate recommendations for discharge while increasing that patient's independence.

Discharge Planning

- Functional Status

- Home Setup/Family Support

- Equipment Needs

- Services Required

- Collaborate

Discharge planning is going to start on day one. When making recommendations, you need to know if they are going to rehab (acute or subacute) versus home with outpatient therapies. Recommendations should also include understanding the client's current functional status related to ADLs, mobility, social factors, family support, and the home setup.

We need to know the accessibility of the home and available equipment, whether basic, like a sock aide, or something more complex, like a stair lift or a Hoyer lift.

We also need to know what services are required at discharge, like OT, PT, or speech.

The medical team needs to collaborate with the case manager to ensure there is an accurate picture of the patient and what the best course of action is.

Interventions

- OT

- ADLs

- Vision/Cognition

- ROM/Strengthening

- Mobility

- Orthotics

- Patient/Family Education

- PT

- Mobility

- ROM/Strengthening

- Seating and Positioning

- Assistive Devices/DME

- Patient/Family Education

OTs focus on ADLs, vision, cognition, range of motion, strengthening, mobility, orthotics, and patient and family education. PT focuses on mobility, range of motion, and strengthening as well. They may also work on seating and positioning, assistive devices, DME, and patient and family education.

- Short Length of Stay

- Line Management

- Discharge Planning

- Communication

Interventions are limited by the length of stay. You may only get one session with a patient, which would include the assessment and intervention. With limited time, you would focus on the biggest deficit impeding the patient's independence. However, suppose you can get more than one session, especially for patients in the ICU. In that case, interventions can be tailored towards whatever the discharge recommendation is and the patient's needs. For example, if we say the patient can go home, OT may focus on ADLS and DME, and PT may focus on stair training and household ambulation. We both will focus on client and family education.

The interventions may also be limited by lines and tubes, as these must be managed at all times. For example, we may need permission from nursing to unplug IV lines before mobility. They may also have drainage tubes or other unseen lines. I like to take a safety pin and pin their gown where that line or drain is to keep an eye on it.

As we said before, the interventions are tailored toward discharge recommendations. The patient may present differently in the a.m. versus p.m., one day to the next, which may affect discharge. Thus, communication is key within the medical team, case managers, nursing, and therapy. When you are thinking of changing or updating a discharge recommendation, it is imperative to have conversations with your counterpart to see if they agree. You also want to contact the case manager as soon as possible to make sure that there will be no issues with insurance or rehab bed availability. Working together and educating them about why you are changing the discharge recommendation will go a long way.

Other Considerations

- Policies and Procedures

- Complex Patients

- Insurance

Other considerations include hospital-specific policies and procedures, specifically in the ICU and early mobility. Knowing that some hospitals have a more conservative approach to therapy and working with people in the ICU is important. Based on the evidence, early mobility is key for better outcomes in this population. If you think rehab is not starting early enough in your facility, you may be able to advocate by presenting evidence to your rehab leadership.

With this population, there can be complex medical complexities, including contractures, comorbidities, and patients plateauing. The medical team may say a patient is too low-level, but in reality, the patient can do a lot. This is why communication is crucial. A chart review might not give an accurate description of what you see in the patient. On the opposite side of the spectrum, you may have a patient in such a fragile state that therapy is on hold. Then when you go back in, they require a reevaluation and a new discharge recommendation. This change may require communicating with your counterpart and case manager and educating the family, especially if they are overwhelmed.

Lastly, insurance can affect discharge recommendations due to their inability to pay, or you may need to see a patient more frequently to justify specific recommendations to insurance. Some insurances require a note to be placed in the chart within 48 hours of discharge. Other things can happen, like the patient needing a procedure or rehab will not accept them because of insurance.

Interdisciplinary Approach

- Co-Evaluations/Co-Treatments

- Screening for Other Disciplines

- Communication

- Education

- Supporting Other Disciplines

An interdisciplinary approach in the acute care setting is beneficial for time management, multitasking in the session for line management and interviewing, and safety. Treating alongside your counterpart also allows you to see the bigger picture of the patient from an ADL and mobility perspective, which you might not be able to do alone.

Screening for other disciplines is key. We are part of a medical team, especially in the acute care setting. If you see significant upper extremity edema or it is red and warm to the touch, you should alert the other disciplines. Things can be missed, so having an extra set of eyes is important.

We also want to communicate clients' responses to our sessions, including their cognition, range of motion, strength, and equipment recommendations or mobility devices. We also want to instruct others in the proper donning and doffing and wear time of orthotics, along with education to family and patients. We can discuss our treatment approaches and implement other disciplines' ideas if appropriate.

The more education, the better, but we need to be mindful that in this setting, typically, the patient and family are still in the active phases of coping and may have selective hearing. We can work with our counterparts to simplify education to maximize patient outcomes.

We also need to think about how we can support other disciplines. Can we add anything to our sessions that would make a difference? For example, as the PT is transitioning a patient to the chair, could they work on some seated upright tolerance and prep for seated ADLs for OT? Could the OT incorporate standing during an ADL task? These small adjustments to our sessions might help the patients meet their goals faster.

Case Study J.K.

- J.K. is a 67-year-old female presenting after an unwitnessed fall with acute right MCA stroke, left shoulder hematoma, left 4th rib fracture, and left pneumothorax s/p chest tube placement and intubation.

- Received tPA, thrombectomy completed

- PMHx: CAD, HLD, HTN, GERD, anxiety, current smoker

- PT Eval Order

- Placed 2 days post-admission

- Is this patient medically appropriate for PT Eval?

- Is any other rehab discipline appropriate?

Going back to our case study, J.K. is a 67-year-old female presenting after an unwitnessed fall with acute right MCA stroke, left shoulder hematoma, left rib fracture, and left pneumothorax status post chest tube placement and intubation. She received tPA, and a thrombectomy was completed. She has a past medical history of coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, GERD, and anxiety, and she is a current smoker. A PT eval order was placed in the chart two days post-admission.

When we go through these case studies today, we will pick out specific discussion points to start thinking about what you would do in this specific scenario. The first point is whether the patient is medically appropriate for a PT evaluation. The patient received tPA upon admission, and it has been greater than 24 hours. They had a thrombectomy yesterday and, per the medical team, needed to lie flat for six hours. Currently, we are past that window. We would call up to the floor to ensure the pain is controlled because of the chest tube placement. We would also talk to a respiratory therapist to see about any plans for extubation, plans about weaning the patient, and if they are stable on the vent.

If all the answers to the questions are yes, they are appropriate to be seen. The next question would be if there is an OT or speech eval placed. Due to a right MCA, this patient likely has left upper and lower extremity weakness, sensory loss, visual deficits, and inattention.

- PT/OT Co-Evaluation

- Why?

- Requires increased assistance for mobility and proper positioning

- Likely to have decreased activity tolerance and endurance

- Early and aggressive mobility

- Why?

We would also assess if the patient is appropriate for a co-eval. If a patient has left upper extremity weakness, neglect, inattention, and requires increased assistance for mobility and proper positioning, they would benefit from several people assisting. We may also expect high pain and anxiety due to that left shoulder hematoma, left rib fracture, and post-chest tube placement. When a patient is intubated, they typically have decreased activity tolerance and endurance, and this patient has been on bed rest on top of all of that for two days. Atrophy of muscles can happen quickly, even lying in bed for an extra hour a day. It is beneficial to mobilize this patient to prevent further effects.

- Patient Interview

- Objective Assessments

- Mobility and ADLs

Katie: Continuing to discuss J.K.'s case, we will discuss how to implement interdisciplinary components of her co-evaluation. First, we can coordinate duties during the patient interview for efficient time management and for the prevention of fatigue, as the patient needs energy for the rest of the evaluation. We want to condense things as much as possible here. To do that, one therapist can begin the patient interview. In contrast, the other therapist works on rearranging the room, collecting necessary equipment, and speaking to the family if they are available, as our patient is intubated. The patient interview will be limited, and we will rely on the family to supplement information.

We can communicate and share information, like range motion and strength, to prevent overlapping assessments, unnecessary pain, and patient fatigue. For example, the PT will assess lower extremity strength, range of motion, sensation, and coordination. At the same time, the OT performs these same assessments on the upper extremities, and they share the information as it is pertinent to the other discipline and not because PTs only look at legs and OTs only look at arms. We are saying the two disciplines do not need to do both. Working together on these assessments and communicating during them will be important for the patient.

Next, we can intertwine PT and OT functional assessments to efficiently use time and equipment, reduce position changes, and conserve energy. This method looks at everything in supine, seated, and standing that needs to be done. We can also assess mobility with ADLs, like transferring to a bedside commode instead of the chair or walking to the sink instead of simply taking a few steps, turning around, and getting back into bed. We can work together to get more done within a session.

Lastly, during mobility and ADL assessments, we can provide increased assistance during mobility to maximize energy conservation and increase function by using two sets of skilled hands, this is especially true with an intubated ICU client like J.K. You are not going to assess for a home discharge at this point. Instead, you are prioritizing early mobility for improved outcomes. Extra skilled hands can also allow us to focus on the quality of movement. As a patient is mobilizing, we can work on the positioning of the hemiparetic extremity. And during ADL tasks in a seated position, one of the therapists can focus on helping that patient maintain an upright seated posture.

Now that we have discussed all the ways to implement an interdisciplinary approach during a co-eval let's walk through an example using J.K.'s evaluation. When we walk in, J.K. is in bed. One of the therapists performs the patient interview while the other therapist rearranges the room and manages the lines in prep for mobility. We split up the objective assessments and complete those. The OT performs supine ADLs like washing of the face. We will work together on rolling and transitioning from supine to sitting. The OT can perform a seated ADL while the PT assesses and assists with sitting balance. We can finish any objective assessments here, completing vision or coordination testing. After this, we do a sit-to-stand trial assessing balance and strength to see if J.K. is appropriate for standing mobility or ADLs.

After this, she needs a rest break; if you were alone, you may have to do that supine. With the extra set of hands, she rests while seated, allowing her to do more things after her rest break. One therapist can position themselves in the back of the patient to give her a solid backrest and maintain good upright positioning, which is important for respiration and pain management. Remember, she has a chest tube and rib fracture and is mechanically ventilated, so her positioning will be crucial.

While one therapist supports her during her rest break, the other can perform passive range of motion interventions or set up the room for the next piece of the assessment. After she takes her long rest break, we ambulate her five feet to the bedside commode, where the OT can further assess her seated balance and provide patient education. We can then do a stand pivot transfer to the bedside chair to work on positioning before the end of our session. This is a good example of how working together and intertwining our assessments allowed us to do more with J.K., which will ultimately benefit her recovery.

Our co-eval findings are that she is alert and oriented times three. She lives alone in a multi-level home and has identified that her daughter may be able to help her after discharge. She was independent at baseline, but she currently requires a mod to max assist for most ADLs and mobility tasks. She has deficits in almost everything, including strength, range of motion, sensation, balance, endurance, coordination, and vision, and she has left inattention. As such, the most appropriate discharge is to an acute or inpatient rehab setting, depending on how she progresses during her stay. Her pain limited her overall tolerance to the session, and we did not know if her daughter could help her after discharge. Both of these things will influence which rehab discharge plan we make.

- Plan of Care/Discharge Planning

- Pain management

- Contact family

- Discharge recommendation

- Goals

J.K. has high pain during mobility, a nine out of 10, and a three out of 10 at rest in sitting. We need to come up with a plan for pain management so that this patient can fully participate in her therapies. We also need to talk to other treating disciplines about timing mobility and ADL sessions with pain meds.

Contacting the family is important here. We need to figure out if assistance is going to be available since it is going to impact what discharge recommendation we make. We find out that her daughter will be able to live with her when she returns home.

J.K. was independent at baseline, is motivated, and her family will assist when she goes home. She could tolerate a 55-minute evaluation vented in an ICU, which is great. We do not have to have finalized discharge recommendations for this patient, but it is looking like acute rehab may be the way to go for her.

- Examples of Possible OT Goals:

- Patient will locate 3 items needed for toothbrushing task with items placed in all visual fields on a table with mod verbal cues to scan visual field as needed.

- Patient and caregiver will be educated and perform daily UE ROM without verbal cues to maintain ROM needed for dressing tasks.

- Patient will complete full upper body dressing task in supported sit with min A.

- Patient will sit EOB with supervision for 1 min without loss of balance in prep for seated ADL tasks.

- How Can PT Help Facilitate These OT Goals?

- Incorporate seated static and dynamic balance tasks in between mobility tasks

- Ongoing education, initiating techniques and cueing for L-sided attention during all tasks

- Perform exercises in a sitting position to work on endurance and sitting balance

- Check in with patient and caregiver to see if they are completing exercise programs

Some possible examples of OT goals include locating items needed for toothbrushing tasks using scanning techniques, performing an upper extremity range of motion program, completing an upper body dressing task, and increasing her static sitting balance in prep for seated ADLs.

PT can facilitate these goals by incorporating seated balance tasks throughout their session, educating her on techniques for scanning the environment during mobility and cueing her for left-sided attention during all tasks. When working on therapeutic exercises, the PT can have her perform them in a seated position to work on the patient's balance and endurance. And lastly, PTs can facilitate OT goals by checking in with her to see how she is doing with her home exercise programs and notifying OT of any issues.

- Examples of Possible PT Goals:

- Patient will perform supine <> sit toward R side, HOB flat and no bedrails, CG A and min cues or less for L UE management.

- Patient will perform sit <> stand using LRAD with CG A, min cues or less for L UE management.

- Patient will perform SPT toward L side with LRAD, mod A and mod cues or less for attention to L side.

- Patient will ambulate 15ft with LRAD and min A, mod cues or less for sequencing and attention to L side.

- How Can OT Help Facilitate These PT Goals?

- When transitioning to EOB for seated ADLs, practice toward R side with HOB flat

- Bring same AD to session when planning to work on standing ADL tasks or transfers

- Ongoing education, initiating techniques, and cueing for L-sided attention during all tasks

- Set up room so patient practices SPT toward L side when working on commode transfers/toileting

PT goals for J.K. include performing supine to sit towards the right edge of the bed, performing sit-to-stand transitions using the least restrictive assisted device, performing stand pivot transfers toward the left side, and ambulating with the least restrictive assisted device. OT can facilitate these PT goals by purposefully transitioning the patient toward the right edge of the bed when getting her up to work on seated ADLs or even purposefully transferring toward the left side when working on commode transfers. Also, the OT can help by bringing the same assisted device that the patient has been working on with PT to their sessions when planning to do standing ADLs or transfers. Lastly, the OT can continue educating the patient surrounding left inattention and trialing new techniques for the patient to maximize outcomes in both disciplines.

When we are talking about these goal slides, these are all examples. Each discipline should plan its session to help the client meet their goals and not focus on the other's agenda; however, having goals that align with the other discipline makes sense for the client. Being mindful of the patient's goals for other disciplines helps us build opportunities to increase the client's independence. These are small changes that are not disruptive but may help them to further meet their goals with the other discipline.

Inpatient Rehabilitation

We will now move into the nuts and bolts of the inpatient rehab phase.

Acute Vs. Subacute

- Acute

- Higher intensity and frequency of therapy

- Frequent physician involvement

- Shorter stays

- Subacute

- Lower intensity and frequency of therapy

- Less physician involvement

- Longer stays

Acute and general rehab centers have a higher intensity, more therapy, increased physician involvement, and shorter stays. Subacute rehabs have lower intensity and frequency of therapy. Typically, the session length is based on tolerance, and there are longer stays.

Inpatient Rehabilitation Overview

- Care Team

- Doctors/Physiatrists

- Nurses

- Case Manager/Social Worker

- Respiratory Therapy

- Rehabilitation Services

- Neuropsychiatry

- Psychologists

- Recreational Therapy

- Patient and Family Members

- Art or Music Therapy

Here is an overview of the care teams, which can vary based on the facility. Some have more, and some have less. It is important to know your care team members so that you can connect patients with them as appropriate.

Ongoing Medical Management

- Blood Pressure

- Pain Management

- Nutrition

- Mental Health

- Stroke Prevention

Medical management remains a very large part of their care in the inpatient rehab phase. Controlling blood pressure to prevent additional strokes, managing pain so that they can fully participate in their therapies, and ensuring that they are getting the appropriate nutrition to support the healing process are all part of medical management. Monitoring and screening for mental health concerns is another critical area. Lastly, we want to educate the client and family on stroke prevention and address habits like smoking, sedentary lifestyles, and unhealthy diets. This education also includes the medical management of risk factors like high blood pressure, obesity, and hyperglycemia.

Inpatient Rehab Evaluation

- Medical Chart Review

- Patient Interview

- Objective Assessments

- Goals/Plan of Care

- Equipment/Orthotic Recommendations

- Discharge Planning

The basic evaluation will look the same in all settings for PTs and OTs, but we focus on certain aspects in different settings. In the inpatient rehab phase, we will focus on the home setup and thorough assessments of impairments and functional deficits, which will drive our discharge planning.

Outcome Measures

Here are the outcome measures.

- OT:

- 9 Hole Peg Test

- Action Reach Arm Test

- Arm Motor Ability Test

- Assessment of Life Habits

- Box and Blocks Test

- Dynamometry

- Executive Function Performance Evaluation

- Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Motor Performance*

- Functional Independence Measure*

- Kettle Test

- Modified Ashworth Scale

- Orpington Prognostic Scale*

- Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement*

- Motor Activity Log-28

- Motor Evaluation Scale for Arm in Stroke Patients

- Motricity Index

- Short Form-36

- Wolf Motor Function Test

- PT:

- 5 Times Sit-to-Stand*

- 6-Minute Walk Test*

- 10–Meter Walk Test*

- Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale*

- Balance Evaluation Systems Test

- Berg Balance Scale*

- Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment

- Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Motor Performance*

- Functional Gait Assessment*

- Functional Independence Measure*

- Motricity Index

- Orpington Prognostic Scale*

- Postural Assessment Scale for Stroke Patients*

- Rivermead Motor Assessment

- Stroke Rehabilitation Assessment of Movement*

- Trunk Impairment Scale

https://www.neuropt.org/practice-resources/neurology-section-outcome-measures-recommendations/stroke

Again, this is not an exhaustive list, but we left it here for your reference. The ones with an asterisk are highly recommended by StrokEdge, and we have provided the reference.

Functional Independence Measure (FIM)

- 18-item standardized test performed at admission and discharge

- Scored on an ordinal scale (1-7)

- Cognition Subscale

- Comprehension

- Expression

- Social Interaction

- Problem-solving

- Memory

- Motor Subscale

- Eating

- Grooming

- Bathing

- Dressing

- Toileting

- Bladder/Bowel Management

- Transfers

- Walk/Wheelchair

- Stairs

Here is an overview of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM). It is an outcome measure most commonly used in acute rehab. This is a breakdown of what it is and how it works. It is at least performed during eval and discharge in acute rehab settings, sometimes more depending on the facility. It captures aspects of cognition, ADLs, and mobility.

Interventions

- Motor Recovery

- Traditional approach

- Sensory stimulation

Alaena: As Katie said, the goal of our inpatient rehab is to get the patient home as independently and safely as possible by progressing deficits, educating the family, and increasing strength, with a special focus on ADLs from OT and mobility from PT.

Traditionally, this is accomplished by motor training, including strength training, range of motion, and mass practice to improve outcomes in stroke patients. However, what we know now is that sensory processing and integration are impaired in the stroke population, and this limits motor recovery. Consideration of these sensory deficits and limitations is important when treating this population.

Motor training is also not purely motor. Movement is the integration of motor and sensory information, so the next few slides will focus on the sensory stimulation approach, which consists of a combination of approaches to load the nervous system in multiple ways to get the most optimal outcome. All of these approaches are utilized by OTs and PTs, and as we go through them, we will highlight how we may use them a little differently within this setting.

First, we have sensory stimulation approaches. This is not a comprehensive list of therapeutic interventions but a summary of what we will focus on today. These interventions are used all the time by therapists, but we want to highlight them here to be intentional when choosing interventions with this population.

Sensory Stimulation

- Somatosensory Approaches

- Electrical stimulation

- Manual interventions

- Constraint-induced movement therapy

- Balance and postural training

- Visual Approaches

- Visual feedback/mirror therapy

- Addressing field loss or neglect

- Auditory Approaches

- Rhythmic stimulation

- Vestibular Approaches

- Reaching, gaze stabilization, balance, and postural training

- Multisensory Approaches

- Virtual reality

- Robotic-assisted training

- Combinations

Stroke patients have impairments in sensation and sensory integration. Sensory stimulation includes somatosensory, visual, auditory, vestibular, and multisensory approaches. In the following areas, we will break them down, including how PT versus OT can use them to obtain different outcomes. We will also discuss how they can work together to achieve optimal outcomes for the patient.

- Somatosensory Approaches

- Electrical Stimulation

- Manual Interventions

- Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy

- Balance and Postural Training

- Weight Bearing

For somatosensory approaches, we will discuss electrical stimulation, manual interventions, constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), balance and postural training, and weight bearing.

Electrical stimulation (e-stim) actively stimulates the paralyzed or affected muscle to get a certain response like increased strengthening or awareness. This can include a neuromuscular or sensory response. You can also use electrical stimulation with a functional task, which is recommended for both therapies. You might hear people call this a functional electrical stimulation approach. It should be used as an adjunct to other interventions.

An example is self-eating because it is a great task to break down and grade appropriately. We can stimulate muscle contraction on the affected bicep using a trigger. This means I am setting the stim up using certain parameters, frequencies, and pulse widths to get the muscle to do what I want it to do. Part of a self-eating task is bringing your hand towards your mouth. We can incorporate the electrical stimulation in elbow flexion and extension or a feeding activity that incorporates holding a spoon and bringing it to their mouth. PT could use functional stimulation differently, like with a Bioness FES, which is more of a robotic device.

We will talk a little bit more about e-stim in part two, but PTs often come out of school able to use them. In contrast, OTs may need to be certified to use electrical stimulation.

Next is manual interventions that combine interventions to improve sensory and positional awareness. It can be achieved through Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) strategies, sensory reeducation such as vibration, and manual facilitations such as massage, stroking, or tapping.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) is an intervention to improve the use of the affected limb by restricting the unaffected one by using a glove, a mitt, a splint, etc. We will talk more about this intervention in part two of this series.

Balance and postural training increase sensory and positional awareness of the body. It includes different static and dynamic balance positions both in sitting and standing.

Weight-bearing will be discussed in more detail in a moment.

- Visual Approaches

- Visual Biofeedback

- Mirror therapy

- Addressing Field Loss or Neglect

- Visual Biofeedback

One visual approach is using biofeedback. This is getting feedback and using your vision using multiple devices. It can be as simple as having the patient intentionally watch a task being performed by a therapist and imitating it back, called learning by observing. It could also be the patient doing a task in front of the mirror and getting real-time feedback, or it could involve a higher-level device. For example, a device called a Vector™ gives an EMG reading.

Let's go back to that self-feeding example. You would put electrodes onto the client's bicep, and the machine picks up any EMG readings from the neurons within that muscle belly. So, if I ask the patient to contract, even if I do not see movement, the machine will pick up those readings. The therapist can create the threshold. When they hit the threshold, the stim turns on, and they get a full motor contraction.

When addressing field loss or neglect, research is very scarce, and most recommend using compensatory strategies.

- Auditory Approaches

- Rhythmic Stimulation

- Auditory Biofeedback

Auditory approaches are next, and this includes rhythmic stimulation and auditory biofeedback. Rhythmic stimulation uses music or another type of rhythm, like a metronome, during gait training to improve stride length and velocity. There is research on using the upper extremity with rhythmic stimulation, but again, research is scarce in that area. One way you could use it is by having a patient perform a bilateral upper extremity task while seated. The idea is to have the patient attend to their affected side.

Auditory biofeedback may enhance motor learning. We can add a sound to help them recognize correct or incorrect motor activities and positions. For example, during OT, I am trying to bring awareness to their left upper extremity during a bimanual task. I could place a bell on that hand for an auditory cue as they are doing a task or a balance activity with PT using a Wii Fit Balance Board. Or every time the patient is not weight-shifting appropriately, PT hits a buzzer so they know they must correct themselves.

- Vestibular Approaches

- Reaching

- Navigation

- Gaze Stabilization

- Balance and Postural Training

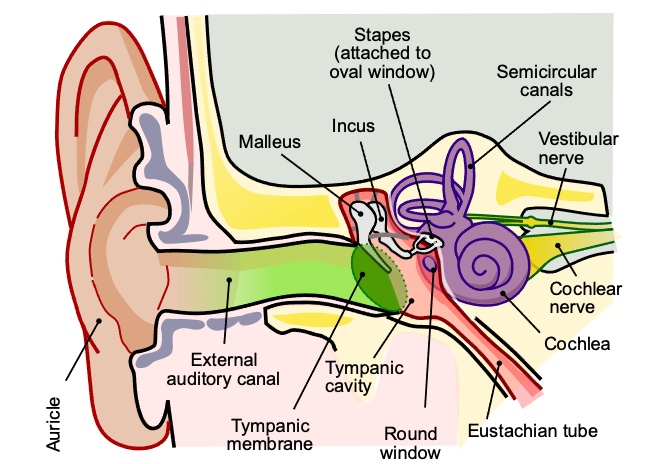

The vestibular system is associated with gait speed, balance, independence, wheelchair mobility, and reaching. As an OT, we do not learn much about vestibular training during our schooling. When I notice vestibular deficits, I collaborate with my PT or another senior therapist to fully understand how to address this central vestibular issue and go from there.

Figure 2. An overview of the inner ear.

- Multisensory Approaches

- Virtual Reality

- Robotic-Assisted Training

- Biofeedback

- Combinations

- Balance and postural training

A multisensory approach combines sensory reintegration using virtual reality, robot-assisted training, and biofeedback.

Virtual reality can improve upper or lower motor function, balance, mobility, and ADLs. However, it must be used with usual care, meaning it should not be the only thing in your treatment plan. You could add some e-stim or balance training while doing this activity. It also should not be done in every single treatment plan.

Robot-assisted training can be used to see improvements in balance, upper and lower extremity function, and midline perception. This intervention will be discussed more in detail in part two of this presentation. There are many robot-assisted options for OTs and PTs. Selecting the right one that is right for your clinic is important.

We have already discussed biofeedback and some of its applications.

Lastly, we can look at a combination of these approaches. For example, in balance and postal training, we use a combination of somatosensory, visual, and vestibular systems.

Weight Bearing

- Bone Mineral Density

- Sensory Retraining

- Balance and Postural Stability

- Spasticity and ROM

- Strengthen Muscles

- Improved Functional Performance

Now, we will take a deeper look into weight bearing. Weight-bearing has many benefits, including bone mineral density, sensory retraining, balance and postural stability, decreasing spasticity, increasing range of motion, strengthening muscles, and improving functional performance.

Increasing bone mineral density is vital because, in this population, there is an accelerated development of osteoporosis combined with high fall risk post-stroke. Due to decreased mobility and hemiparesis, disuse is a problem post-stroke.

Sensory retraining is important to bring awareness to joint subluxation through approximation and weight bearing.

Improper weight bearing leads to postural instability and sway. Bilateral weight bearing through the limbs increases strength.

Weight-bearing can also counteract dominant flexor synergy or spasticity to improve functional performance.

Figure 3 shows me in my clinic. Weight-bearing is applying pressure through the upper and lower extremities in various positions.

Figure 3. Weight-bearing in quadruped.

You could have the client complete weight-bearing prone on extended arms or with forearms propped, posterior prone sitting, anterior or lateral weight-bearing on walls, or while sitting, in quadruped, tall knee, or standing. Therapists can achieve these positions using different equipment. For example, during OT, if I do have an extra set of hands and have someone who cannot keep their elbow extended or follow directions, I may use some of the equipment and positions shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Different positions for weight-bearing through the arms.

As you can see in the very first one on the left, there is a slight asymmetry in the shoulders. We could get the patient into prone with a foam pad to assist with positioning.

Next, we are looking at a quadruped position, using a knee immobilizer on the left arm due to instability or weakness. You could also use e-stim to help. This allows a therapist to free up their hands to focus on approximating the shoulder joint or weight-shifting right and left at their hips.

Lastly, the last image shows weight-bearing through the forearms. Let's say we have a patient with an unstable wrist or pain in their arm. This position can get the same benefits of shoulder approximation. This prone position is also good for stretching flexor synergy patterns at the hips.

Katie: From a PT perspective, we will use weight-bearing tasks for the same purposes as OTs for strengthening muscles, sensory retraining, balance, and postural stability. Weight-bearing tasks can be performed in various positions depending on your patient's deficits and goals.

Looking at Figure 5, we can use these different positions.

Figure 5. More weight-bearing positions.

Using a ball or something underneath the patient to support their trunk allows the patient to focus more on their positioning versus simply holding themselves up in this position. In the middle, this patient seems to be leaning into the ball, looking for more support, which means that her knees are not underneath her hips. This is an ineffective position to work on weight-bearing. We may need to get a bigger ball or something more supportive to allow her to achieve the optimal position of her knees underneath her hips.

The far right image shows the client shifting her weight toward her strong side and away from her hemiparetic or weak side. We may need to facilitate a good weight shift toward the impaired extremity for strengthing and sensory input.

Task-Specific Training

- Principles

- Motor learning

- Experience-dependent neuroplasticity

- Shaping technique

- Example

- Self-feeding task

Alaena: Task-specific training has three principles, including motor learning, experience-dependent neuroplasticity, and shaping techniques. Motor learning refers to permanent changes in behavior because of practice and experience or the actual task at hand.

Experience-dependent neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to reorganize itself in response to practicing a task, which includes varying environments and components of the task during other exercises or activities.

Shaping is a training method in which a motor or behavioral objective is approached in small steps by successive approximations. The task is made progressively more demanding as the patient's abilities enhance.

We are seeing much more in the research for task-specific training with OTs. Figure 6 shows an example of this with self-feeding.

Figure 6. Self-feeding task.

First, we look at the components of self-feeding, including reaching, grasping, grasp and release, elbow flexion, extension, supination, and pronation. We can start with the patient working on hand-to-mouth patterns and progress to cutting the food. She uses a universal cuff for the fork and curved plate, and her unaffected arm cuts. She also has a wrist brace and is practicing reaching. We could grade this activity by having her stand.

Gait Training

- High-Intensity Training

- Treadmill vs. Overground

- Body Weight Support

- Sensory Stimulation

- Improving Physical Activity

- FES and AFOs

Katie: The level of ambulation following stroke is a long-term predictor of participation and disability. We will talk about this more in part two of this presentation as there is so much research coming out about high-intensity training It is said to lead to improvements in gait speed, strength, and even outcome measures such as the Berg or the Six-Minute Walk Test when compared to traditional gait training.

Let's break down what we mean by high-intensity and traditional training. High-intensity training means mass locomotor practice at high aerobic intensities or 70 to 85% of age-predicted max heart rate for 45 to 60-minute sessions. In contrast, traditional gait training in an inpatient rehab setting averages only about 250 steps per session, with less than 5% of all sessions meeting recommended aerobic exercise thresholds. With high-intensity training, patients average thousands of steps per session. It is quite a big difference. Incorporating high-intensity gait training into your treatment plan for stroke patients is highly recommended throughout the literature.

Outcomes for treadmill and overground training are the same. You may see more improvements in gait speed using treadmill training. The use of body weight support during gait training benefits the stroke population. Still, it should not be used exclusively as the literature does not really support it as a primary treatment method.

Improving overall physical activity during non-therapy times has been shown to promote recovery of gait independence within the first-month post-stroke. Thus, it is important to work with your facilities to keep these patients active during non-therapy times, like with activity groups or wheelchair "walks" around the building.

The use of functional e-stim and AFOs are associated with improved muscle strength, increased gait speed, improved foot and ankle positioning during the gait cycle, improved dynamic balance and walking endurance, and improved overall mobility in patients post-stroke. We must think about recovery versus compensation when discussing functional e-stim and AFOs. Functional e-stim, such as the Bioness and walking aids, are mostly therapeutic and will promote motor recovery.

AFOs are typically chosen mostly as a compensatory strategy. However, research shows that the less restrictive AFOs can have therapeutic benefits by allowing for the activation of the gastrocnemius soleus and tibialis anterior.

In the acute and subacute phases of stroke recovery, we will choose interventions that promote the recovery of function. In the chronic phase, we use our clinical judgment based on the patient's presentation to decide whether we are promoting continued recovery or compensation.

Barriers

- Spasticity

- Contractures

- Movement Disorders

- Cognition

- Caregiver Support

- Home Setup

- Coping/Mental Health

Alaena: Now, we will touch upon barriers to discharge and intervention. We will look at the majority of these barriers, including spasticity, contracture, movement disorders, cognition, caregiver support, and home setup, in part two.

- Coping and Mental Health

- Coping (Rapoliene et al., 2018)

- More than 50% of survivors remain temporarily or permanently disabled

- Only 20% of survivors return to work

- Motivation affects outcome

- Depression (Tsao et al., 2022)

- Approximately 1/3 of stroke survivors

- Highest frequency in 1st-year post-stroke

- Associated with higher mortality and worsening function

- Coping (Rapoliene et al., 2018)

The one we will focus on today is coping and mental health. It is important to note that during an inpatient stay, the patient is still in the early days of a stroke. Depending on their length of stay in the acute care setting and the resources and support available, the patient and family may still be trying to process what this new diagnosis means for them or their loved ones.

Coping has five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. As providers, we must be mindful of where that patient and family members are in the coping process, especially as we prepare them for discharge. Their coping stage is reflected in the goals and interventions. In general, we need to do a better job of addressing mental health at this stage of rehab. They may be angry, anxious, or depressed.

Here are some statistics. More than 50% of survivors remain temporarily or permanently disabled, and only 20% return to work. Throughout the literature, motivation is determined to affect mental health outcomes, especially depression. And approximately a third of stroke survivors are diagnosed with depression. We see the highest frequency of depression in the first year, which is associated with higher mortality and worsening function.

To help with this, we need to build positive relationships with the client, which has shown to be effective. We also need to educate the patient to address post-rehab uncertainty, even if it is a difficult conversation to have with them. We want the patient to become a specialist in their care by advocating and assisting in the therapy process. You can give them simple choices of what to do for the day or a "home" program they can do in their room. They can then educate the family on how to perform it.

Empowering and motivating patients has a huge impact on their overall care. We can provide specific feedback on actual improvements instead of the deficits. This patient has been in acute care, and now they are coming to an inpatient hearing, "It is going to be difficult to do XYZ when you go home." We want to highlight what they are doing well as this will have a huge impact on their psyche.

Lastly, we want to advocate for the patient by referring them to services through their medical team, like social work and neuropsych. A rehab hospital may have support groups or one-to-one peer interactions. Sometimes, it is easier to talk about what is going on with one person, especially someone who has been through it, versus a whole group. Be mindful that these patients are the experts in their care. Just because we see stroke patients, we do not know what they are going through. Finding someone to talk through things and discuss strategies will have a huge impact on their outcomes.

Literature Update

- Critical Window

- Enhanced neuroplasticity triggered by injury

- Largest functional gains in first 3-6 months post-injury

- CPASS study

- Gains in chronic stroke

- Enhanced neuroplasticity triggered by injury

The literature discusses neuroplasticity and the critical window timeline. This window is when the patient is going to make the most gains. This is constantly being researched and has changed throughout the years. Typically, the largest gains have a three to six-month mark. We can see gains from the chronic stroke population, but they are lower and not as intense. What we do not know is if these slower gains are because they are not in intense rehab or if this is just how the trajectory of that stroke diagnosis will go.

A current study called CPASS is moving into phase two clinical trials. It focuses on the upper extremity motor recovery and looks at intense therapy in the early acute care phase to see if this provides the most optimal outcomes. These neuroplasticity studies are crucial to know if gains can be made throughout this diagnosis.

Interdisciplinary Approach

- Co-Treatments

- Screening for Other Disciplines

- Communication

- Education

- Supporting Other Disciplines

To wrap up, we will look at the overall interdisciplinary approaches in in-patient care as they are necessary and beneficial. We know that co-treats are rarer in this setting, but sometimes they are needed.

We can screen for other disciplines and refer to them, like social work or psych.

In the setting, there is more of a focus on rehab services, so medical communication is super important. We can also observe our clients in different environments with our counterparts. We can support each other by talking through scheduling conflicts, goals of care, equipment recommendations, and how to don and doff different orthotic devices. Let's say PT goes on a community outing with patients. They can report how that patient navigated obstacles, reached for objects, or performed cognitively. Vice versa, if OT takes a patient out for a community outing, OTs can then communicate to the PTs on mobility, stair climbing, et cetera. Another example is that if PT sees patients in the morning, but the OT needs to work on ADLs, they may be able to switch times.

The next area is the education of the patient and family, again being mindful of their coping. We need to meet them where they are and provide an appropriate education for them right now. Some literature shows that carryover of home rehab programs is typically done when three or fewer exercises are included. We need to think of these same principles when educating families and patients. We must prioritize what we want them to hear for carry-over.

Lastly, we want to incorporate other disciplines' goals into our interventions to achieve optimal client benefits.

Case Study J.K.

- J.K. was discharged to acute rehab 12 days post-stroke. Hospital course complicated by respiratory status 2/2 PTX, intubated x6 days, and chest tube x10 days. Discharged on 2L 02

- Patient’s daughter will become primary caregiver and live with patient upon discharge. She can only take 2 weeks of leave from work

- A&Ox4, follows 2-step commands consistently, requires cueing for L inattention

- Mod to max A for all seated and bed-level ADLs

- CG/min A for sitting balance

- Mod/max A for transfers/gait with left lean

J.K. was discharged to acute rehab 12 days post-stroke. The hospital course was complicated due to her having a pneumothorax, being intubated for six days, and having a chest tube for 10 days. She was also discharged on two liters of oxygen.

We now know that the patient's daughter will become the primary caregiver and live with the patient upon discharge. However, she can only take two weeks of leave from work.

The patient is now alert and oriented times four and can follow 2-step commands consistently. They require cueing for left inattention, mod to max assist for all seated and bed level ADLs, contact guard to min assist for sitting balance, and mod to max assist for transfers and the gait with a left lean. In the acute care setting, J.K. had three OT and four PT sessions. Not much has changed from that acute care except for mild improvement in activity tolerance, balance, pain, and range of motion. Since not much has changed from the acute care to the inpatient setting, we will not go through a whole evaluation.

Case Study J.K. Goals

- Examples of Possible OT Goals:

- Patient will complete full upper body dressing task with min A.

- Patient will attend and use left UE for 75% of meal prep activity with 2 verbal cues as needed.

- Patient will be able to reach towards target with left UE in 2 out 5 trials accurately while in side-lying to increase strength needed for ADL and community reintegration.

- Patient will perform bed mobility with supervision to inc. independence needed for ADL tasks.

- How Can PT Help Facilitate These OT Goals?

- L UE approximation and use of L UE during tasks

- Reinforcing OT technique when putting on jacket or changing clothes

- Scapular PNF for proximal strength and stability

- Focus on bed mobility technique when transitioning on/off mat for exercises

Above are examples of OT goals and how PT may be able to support.

- Examples of Possible PT Goals:

- Patient will perform supine <> sit from R EOB independently with HOB flat and no bed rails.

- Patient will perform SPT toward both R and L sides from various height surfaces using SBQC requiring supervision, min cues for safety and L inattention.

- Patient will ambulate 100ft with SBQC and CG A, min cues for L inattention.

- Patient will ambulate over and around static obstacles in path with CG A using SBQC, mod cues or less for attention to L side.

- How Can OT Help Facilitate These PT Goals?

- Practicing SPT toward L side when working on commode transfers/toileting

- Bed mobility practice and techniques, practice bed mobility on/off mat

- Incorporate standing endurance and balance tasks such as standing ADLs into session

- Refrain from setting up environment prior to walking to the bathroom, try gift shop/cafeteria

Katie: These are examples of PT goals and how OTs can support them.

Case Study J.K. Interventions

- OT Interventions

- ADL Training

- Strengthening

- Vision Strategies

- Fine Motor Interventions

- Reaching

These are a few interventions that the OT used in J.K.'s case, working on strength, fine motor, and reaching using sensory motor approaches such as robot-assisted activities, e-stim, constraint-induced movement therapy, and mirror therapy. They worked on visual strategies such as techniques for left inattention, scanning the environment, and making checklists to ensure that the patient collected all the items needed for an ADL task, like toothbrushing. They also used a sticker on the patient's arm to improve attention during mobility and ADL tasks.

Ways that PT supported the OTs interventions include working on transfers, seated balance, and standing balance, and encouraging the use of the upper extremity, such as reaching for the bedrail and reinforcing the visual strategies implemented by the OT so that the patient gets more practice.

- PT Interventions

- Targeted Strengthening

- FES + High-Intensity Gait Training

- Obstacle Course

- VR for Balance

- Mobility Training

Again, this is not a complete list of PT interventions, but these are some areas to highlight. PT used therapeutic exercise with e-stim and PNF patterns and combined functional EIM with high-intensity gait training. They also used obstacle courses for balance and to reinforce left inattention during dynamic tasks and balance training with a VR device. They also worked in quadruped and tall kneeling positions for weight bearing and mobility training to address bed mobility transfers and stairs.

Ideas for ways the OT can assist with PT interventions include cueing for equal weight bearing during standing activities and using ADLs to work on static and dynamic balance. Of course, it is important to use the same assistive device that the patient has been working on with PT when performing transfers, standing ADLs, and continuing to work on strategies for vision and left inattention. As we've said previously, co-treatments in the acute rehab setting are certainly less frequent than in acute care, but there are scenarios where co-treats are appropriate.

- Co-Treatment Example

Let's talk about an example of a situation where a co-treat would be appropriate for a patient like J.K. The OT working with a patient has been trying to progress standing ADLs, but J.K. has not progressed much. She keeps losing her balance, her left knee buckles, and she cannot keep herself in an upright position long enough to complete an ADL. The OT looks through the recent PT notes to see what the PT has been working on and notices that PT has been working heavily on standing, balance, and gait using high-intensity gait training. She reaches out to PT to discuss the discrepancies of why the patient is doing so well with these standing activities in PT and not OT. They decide to work together to progress the standing ADLs for this patient. This is a great example of a time when a co-treat can benefit a patient.

Much is going on during a standing ADL task. For a standing ADL, they use an elevated table. The OT focuses on ADL activity, facilitating upper extremity coordination and motor control. In contrast, the PT focuses on balance and positioning, facilitating equal weight bearing and cueing to keep the left knee straight throughout the task. They may need to modify the ADL task if the task is too hard and advance as able.

Case Studies

Now, we will review four additional case studies.

Case Study 1

- Eval Findings in Acute Care

- Eye-opening but weak/fatigues easily, vertical and horizontal eye movements

- Minimal R cervical rotation in gravity eliminated plane, trace R upper trap contraction

- Communication established via eye movements when therapist holds eyes open

- A&Ox3 (name, place, time)

- Diagnosis: Locked-in Syndrome (incomplete form)

- Discussion Points

- Functional expectations

- Therapy goals

- Discharge planning

Case study number one is a 42-year-old male status post bilateral pontine infarcts. He initially presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of three, and the medical team deferred a therapy evaluation pending a family meeting about the goals of care. After a week, the family elects to trach and PEG the patient, and therapy orders are placed. Due to staffing, therapy cannot get in to eval this patient for another five days. The patient has begun opening his eyes when sedation is lowered. The medical team states that the patient is not doing anything other than opening his eyes, and they suspect locked-in syndrome.

Here are some discussion points. Is this patient appropriate for a PT/OT eval? When we are talking about a locked-in syndrome, the answer is yes. He may be a good candidate for a co-evaluation as he will have very low activity tolerance. We may only be able to turn off the sedation once, depending on his medical status.