Editor’s note: This course is a transcript of the webinar, A Comprehensive Review of Current Physical Therapy Treatment for the Lumbar Spine, presented by Ellen Pong, DPT, MOT, BA.

Objectives

- The participant will be able to identify at least three difficulties in selecting effective physical therapy treatments for patients with low back pain.

- The participant will be able to identify at least two conclusions of recent systematic reviews of conservative treatments for patients with low back pain.

- The participant will be able to describe at least two examples of current knowledge in conservative treatments for patients with low back pain.

Introduction

A popular opinion among many healthcare practitioners and payers is that the majority of patients with low back pain will eventually get better no matter what you do. You might have heard that before. I remember the first time I heard that statement, I was a physical therapy aide and one of my responsibilities was to obtain insurance authorizations. A woman I spoke with denied the patient's authorization beyond one visit and her words to me were, "According to my evidence, people with back pain will get better on their own no matter what anyone does so he doesn't need physical therapy." At the time, that blew my mind. I thought then, as I still do now, that many times study results are turned in favor of the payers rather than of the patients.

Evidence supports that pain and disability from the first episode of acute low back pain does resolve by itself in the short-term. This follows what we usually see in practice. Unless the first episode of acute back pain was caused by a significant injury such as sports or on the job, the patient often does not see the physician. Some of these patients may see the primary care physician to receive palliative medications such as ibuprofen, opiates or muscle relaxers, of that type. They do not return to the physician unless the pain has persisted.

Those who return to the physician may be referred to physical therapy for palliative care. However, more often the injury is then thought to be severe enough to warrant films and referral to a specialist. Now, I have to modify this statement just a bit, remembering that some payers do not allow films beyond plain films such as MRI until the patient has undergone six weeks of conservative care, which would be physical therapy. Regardless though, it is true that most of the time the outpatient therapist will not encounter many patients in the true acute stage of low back pain.

Can you see pathology in Figure 1? There is a fracture of the pars, so there is a spondylolisthesis. If this were a posterior oblique view, we would notice that the Scotty dog then has a collar. That one was a particularly interesting one to me because it is something that I have and that I actually found on my own films before they were even reviewed.

Figure 1. Fracture of the pars

What the proponents of the “back pain as self-limiting no matter what you do” belief failed to consider is that the course of low back pain is that of recurrence rather than our usual definition of acute or chronic. Injure, heal, and then re-injure- this cycle repeats itself with acute and chronic phases repeating often becoming progressively severe with time. Although we will explore palliative treatment in this course, most of the treatment in the evidence presented will be appropriate to patients with chronic phases of recurrent low back pain or continuous chronic low back pain.

Clinical Prediction Rules

Are you familiar with clinical prediction rules (CPRs) and do you use them to direct your plan of care? I have mixed feelings about them so we are going to talk about them in this course. When we treat patients with peripheral pathologies such as rotator cuff tears, distal radius fracture, and sprain of the anterior talofibular ligament, we often treat in a tissue-specific fashion. This is not true a 100% of the time; however, it is often.

When we treat people with low back pain, both conservatively and post-operatively, often the pathologies involved many tissues. For example, I have anterolisthesis Grade 2, as I mentioned, at L5 and S1. I have a herniated disc at L3-4 and hypermobility of the right sacroiliac joint. Furthermore, what is visible on the MRI or plain film is not necessarily what is causing the patient's pain and dysfunction. For example, my sacroiliac joint hypermobility will not be visible on a static film, yet it ranks number 2 in the cause of my most frequent pain. I know that a favorite trick of certain individuals is to take a look at the films and point out something that is wrong and say, "There it is. That’s what’s wrong with you." Well, yes, it is what is wrong, but it may or may not be what is causing the pain.

Patient Example

Suppose that I am your patient. With my back pain due to multiple tissue specific pathologies, can you then select a treatment that is proposed to be helpful for patients with herniated discs or should you choose those helpful for patients with anterolisthesis? If I perform an extension based exercise program for the herniated disc, I will increase the pain from the anterolisthesis. Can you really choose treatments based only on the tissue involved? With many patients, we are often not told what the specific pathology is. We are given a referral that says back pain. I have often seen therapists (when not given a diagnosis on the referral) fail to remember that a person can and often does have more than one thing wrong at a time.

Definition

More recent studies of best treatment practice for patients with low back pain have attempted to define a set of rules or standards. Patients whose signs and symptoms match these rules derived from the evidence will benefit from a specific treatment. These are called clinical prediction rules.

These CPRs are not infallible and are not meant to be used as a cookbook. In fact, studies often conflict in support of specific rules. They basically argue back and forth. Remember that most CPRs have not yet been validated. They have been presented but they have not been tested to make sure, (other than the original study), that they are valid. Our research is truly in its infancy, yet we can use this preliminary work to give general ideas and direction. We can use the CPRs without the CPRs using us.

Layout of Conservative Treatments

For this course, I will present CPRs and evidence specific to treatments. We will be looking through exercises starting with stretching and flexibility, stabilization including motor retraining, strengthening, manual therapies of the bones and joints and soft tissues, modalities, and alternative/experimental treatments. There are more treatments than these, but I am going to discuss treatments that have some reference or coverage in the literature even if it is not favorable or the best science.

Exercise in General

Specific Exercises

Currently, exercises are not recommended for patients with acute low back pain with a few exceptions. Height and Associates in 2001, tested long-term (up to 3 years) effects of basic (multifidus work on a stable surface) stabilization exercises in patients with first time acute low back pain. They found that specific exercises may be more effective in reducing recurrences of low back pain than medical management alone. Note the emphasis on specific exercises. The immediate goal is to avoid increasing pain or injury. We want to avoid causing the patient statement you might have heard before: "Well, I tried physical therapy but they only made me worse."

Tai Chi

Another exception is by Yang and Associates in 2015. They tested basic tai chi exercises versus a stretching program in their abilities to enable posture maintenance with lesser force, improve balance ability and decrease low back pain in young women with acute low back pain. Results were positive for both but greater for the tai chi group.

Multiple Types of Exercise

In general support of exercises as treatment, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials (Searle, Spink, Ho & Chuter, 2015) was recently published exploring exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain compared to modalities, massage, manual therapy and weight in which they received no physical therapy treatment. Their result suggested that strength or resistance and coordination/stabilization exercise programs have superior results in decreasing pain over other interventions in the treatment of chronic low back pain.

Keep in mind that often these studies are crowded with noise. The experimental group does not receive only the treatment that they are being tested with. They may receive, for example, exercises with manual therapy or exercises with modalities and then be compared to control groups who received all of the above except for exercises. At the end of the day then, we really cannot say that the exercises themselves made the difference. Although, I have seen that they do try to say this in the literature.

Exercises: Stretching/Flexibility and Mobility Exercises

After some lengthy searching, I was unable to locate established CPRs for the specific intervention of stretching flexibility exercises in patients with low back pain even after consulting Glynn and Weisbach reference manual, Clinical Prediction Rules: A Physical Therapy Reference Manual. At this time, published CPRs for treatment of low back pain appear to be limited to manual therapy manipulation and to stabilization exercises. Additionally, it is difficult to find the effectiveness of stretching as an isolated intervention. Stretching is normally part of a larger treatment program. For example, how many times you have treated a patient for any problem with only stretching? That is not usually the way we work as rehab professionals. We try to offer all the tools we have that are beneficial for the patient's best benefit. With that said, we have to remember that studies of any specific treatment need to start with isolating that treatment and proving that it does do what we think it does. Then additional studies can assess the effectiveness of this proven valid treatment in a combined treatment plan and report on that aspect.

Stretching is favorably reported in the literature for effective use of low back pain when combined with strengthening. Most evidence for mobility exercises focuses on the repeated movements and stretches advocated by McKenzie or on the self-mobilization techniques of Mulligan (Kennedy & Levesque, 2015). I want to mention that McKenzie and Mulligan techniques may not be what we think of when someone says stretching flexibility exercises probably because their purpose is more comprehensive than a muscle stretch. Yet, I am seeing them included in this classification more and more so I have done so as well here.

Muscle Tightness

As far back as the 1980s, the literature has suggested that lumbar and hip muscle tightness is present in patients with low back pain (Kennedy & Levesque, 2015). I can say from my own part that if you have to sleep with a pillow beneath your knees for 20 plus years in order to decrease the pain enough to sleep, you will develop hip flexor tightness. You can stretch all you like but after 6 or more hours a night for years in a shortened position, the muscle and tissue will have its way. Therefore, do not forget to discuss sleeping positions with your patients as part of their stretching and mobility. We as a profession had been dilatory in providing evidence to support this suggestion. Indeed, Foreman and peers demonstrated that success in hamstring lengthening has made no change in lumbar mobility or curvature. Currently, many therapists include hamstring, hip flexor, and tensor fascia latae stretches in exercise programs for low back pain and this may be simply by rote or cookbook rather than from thoughtful application.

Length Changes

Does stretching really add length, additional sarcomeres to the hamstrings, and is this accomplished with 30-second stretches? If that were the case, then why would we be having serial casting, dynamic splinting and Z-plasty surgery employed to lengthen muscles? I do not believe that 30-second stretches or 10-second stretches performed in the clinic and/or at home add measurable actual length to the muscle. My opinion is based on my knowledge of the subject and not on anything in the literature. What is it that we are seeing when the patient is able to touch fingertips to the floor after a week of stretching? I believe that the difference is the ability to access the full length or greater length of the muscle than before the stretching began. The original length has not changed. This is a functional rather than a structural change. Stretches performed for 2 minutes and less do seem to allow relaxation of the muscle. If the muscle is relaxed, more of its true length may be utilized. Perhaps this is the reason why increases in hamstring muscle length have not shown a cause and effect with changes in lumbar mobility or curvature.

If you have attended orthopedic surgeries, you may have seen the extensibility of the joints as the surgeon moves the patient's limb into position. The muscles are flaccid at that level of general anesthesia. All of the muscle's true length is apparent, which we do not see when the person is conscious and the muscle is toned or even tensed. Another factor to consider is that the muscle tenseness we encounter with pain. When you hurt to move, your muscles tend to automatically guard against movement, increasing their tension even at rest.

Role in Treatment

Does this mean that we should omit stretching from treatment for low back pain? We must ask ourselves a few questions as to what we think we can accomplish and what our motivation for is in utilizing these stretches. First, is a relaxed muscle likely to pull less on a painful muscle joint or other structure? Probably. I can not say for certain, but logic and reasoning tell me that a relaxed, more elastic rope will pull less than a tight one, and nothing that is painful benefits from being yanked on constantly. Next, are the stretches we choose to use causing increased pain or injury to the patient? If we are causing an increased pain to the patient with stretches, then we are rather defeating our purpose here. I am a big fan of stretches that use gravity as the force so that the position can be maintained for 2 to 5 minutes without additional tension, simply taking the muscles and joint tissues to their non-painful limit and consciously relaxing there. Then last, are we using them to add time to our charges for treatment as fillers? I hate that last question, but we have to answer it very honestly, as I am the first to say that some clinics do tend to emphasize billable units and productivity of the therapist. This challenges us to walk a fine line in our ethics between meeting the productivity standards and treating the patient with only what is needed and beneficial. These exercises, like any others, are not condiments like salt to be sprinkled into a treatment plan for a balance of stretching, strengthening, modalities, and manual therapy. There must be a specific need and purpose for them. This way we can justify including treatment that is not yet supported strongly in the literature.

Recommended Stretches

Which stretching exercises are recommended? Very few specific stretches have been supported in the literature. Therapist-assisted hamstring stretching (Kennedy & Levesque, 2015), a jackknife hamstring stretch (Sairyo et al., 2013), lunge and propped prone hip extension to stretch hip flexors (Kennedy & Levesque, 2015) were supported. At times, a list of ideas is helpful. Let me add quickly that a propped prone hip extension stretch may not be ideal for those with anterolisthesis. Pay attention to the patient's report of pain and where the stretch is felt, where the pain is felt, and how this changes with the duration of the stretch when properly done.

Lumbar Extension

Most of you are probably very familiar with exercises to facilitate lumbar extension. They include the prone press up, the prone unilateral leg lift, the supine anterior pelvic tilt, quadruped extension, a standing back arch, forward lean at the wall, and self-mobilization using your hand or a strap or even a towel to localize.

Lumbar Flexion

To facilitate lumbar flexion, we have the supine knee to chest both single and double knee. For somebody who is rather heavy, a towel looped under the knee really helps to bring the knee forward to the chest because they have trouble reaching the knee when they are hook lying. Other exercises include the posterior pelvic tilt, the forward curl (which you can perform on the therapy ball), jackknife, quadruped flexion angry cat, and quadruped while sitting back in child's pose. Some therapists are familiar with an exercise called the “prayer stretch” and that is what we are now calling the “child's pose” probably to be neutral and patient-friendly in our terminologies. There is also flexion over the end of the bed while utilizing contract relax, and self-mobilization again using a hand or strap or towel to localize.

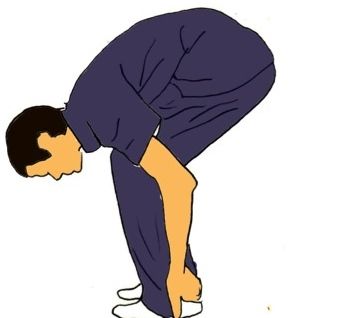

Jackknife. A few pictures I saw in textbooks were not correct in regards to the jackknife stretch, so I went to a source (Sairyo, et al., 2013) that utilized the stretch in their study. In the starting posture Figure 2, the patient squats while holding his or her ankle joints with the hands. Please note to watch those patients who have painful arthritic knees or even joint replacements of the hips or knees. This may not be appropriate for them. Also note that many patients are unable to attain that starting position with feet flat on the floor, so you may want to stand by to give a bit of support against their wobbly loss of balance. The patient then gradually extends the knee joints (Figure 3), and at this point, their feet should be able to come flat on the floor while maintaining contact of the chest and thighs. That part is very important. Maximum extension is reached when the quadriceps femoris is at maximum contraction. The maximum extension position is held for 5 seconds. Again, a short period of time but it must have its uses. It had positive results in the study.

Figure 2. Starting position for Jackknife

Figure 3. Second position for Jackknife

Lumbar Side-Flexion

To facilitate lumbar side flexion (Kennedy & Levesque, 2015), the following can be utilized: the standing lateral glide, side lean into the wall, the side flexion in child's pose (as you walk your hands across the floor laterally), pole-side flexion, lateral pelvic tilt with hip hike drop in standing and in supine, and also side lying. Pole side flexion is lacing a pole behind the back with arms looped over and leaning to the side. The challenge here is to maintain form and do not allow the patient to combine other planes of movement. For the standing hip hike and drop, the drop may cause pain to someone who has laxity or hypermobility in the sacroiliac joint. Be aware of pain reports with this activity especially with female patients who release that hormone relaxant every month and those who have had multiple children. That population has an inherently greater risk of weight-bearing joint laxities without trauma than males do.

Lumbar Rotation

To facilitate lumbar rotation, we have the quadruped thread the needle, pole rotation, and spinal twist. For the thread the needle stretch, the patient in quadruped rotates and lowers their trunk until his or her bottom arm is lying flat out to the side and his or her face is pointed in the same direction as that bottom arm. The top arm is bent at the elbow and supports the trunk with the hand flat on the plinth or floor. This also looks to be stretching the posterior capsule of the glenohumeral joint, so be cautious in anyone who complains of shoulder pain in the stretch. I would also caution that some of the exercises might not be suitable for the elderly with arthritic joints and/or those with limited functional mobility who may have difficulty getting in and out of these positions independently and safely. Please pick your exercises specifically and carefully.

New Direction in Stretching

A new direction in stretching is surface electromyographic biofeedback assisted stretching (SEMGAS) for the treatment of chronic low back pain. This was explored in a case series by Moore, Manion, and Moran (2015). Their conclusion was that electromyographic biofeedback used alone with a limited dose could be effective at improving impaired flexion relaxation in some individuals with chronic low back pain.

Definition. Flexion relaxation (FR) is a muscle activation pattern where the lumbar paraspinal muscle activity decreases near maximal voluntary flexion (MVF). Flexion relaxation is commonly attributed to the change in spinal load-bearing structures from the muscles which contracts eccentrically to control the flexion movement, to the passive structures including spinal ligaments, discs, and fascia. As the posterior passive ligaments become increasingly tensioned during flexion, our stretch receptors located in those posterior elements produce this reflex, which acts to inhibit the paraspinal muscles.

Individuals with chronic low back pain (LBP) commonly display an abnormal FR maintaining substantial muscle activity. They cannot turn it off. This absent flexion reflex can reportedly identify 86 to 89 percent of chronic low back patients from asymptomatic individuals. While a reduced FR response appears to present as a positive adaptation response to acute injury, acting like a biological splint, aberrant muscle patterns and persistence of activation may also partly contribute to the chronicity of chronic LBP. I find this to be true in a number of other joints as well. Some of you may have noticed patients who have had long-standing knee injury, the medial aspect of the quadriceps has been inhibited a long time. It is atrophied and almost gone away. Similarly, we have the inhibition of the tibialis posterior in an ankle sprain. It is a kind of protective reflex meant acutely, but the problem is if the injury continues into the chronic phase, it is hurting us more than helping us.