The Changing Landscape in America

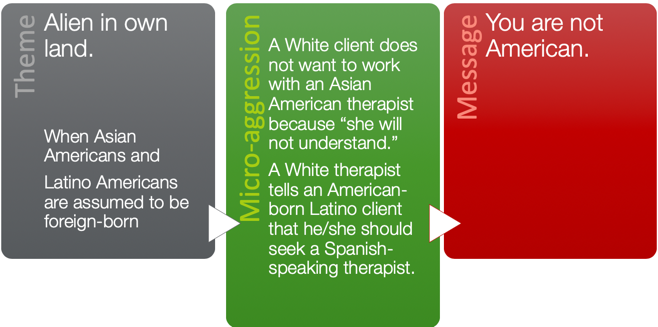

Thank you so much. I am delighted to be here to talk about "the elephant" in the room these days. This is one of my favorite topics because it was part of my dissertation during my doctorate program. It was specifically designed for early intervention. There is no doubt the cultural landscape is changing in the United States and racial and cultural issues are paramount for healthcare professionals. I am going to start by talking about statistics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Racial breakdown in the US.

(Source: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/)

The Pew Research Center is where I got this information. It indicates that the proportion of immigrants in the US population is actually approaching a record term high. It's about 13.6% of the population, the highest since 1910. The household income in the United States is also near high. However, there is some inequity among racial and ethnic groups, and this plays a factor in racial disparities. Also, more broadly, the public also sees differences by race and ethnicity, when it comes back to getting ahead in the United States and access to services, and these statistics on the slide indicate that. The majority of Americans, 56%, say that being black hinders a person's ability to get ahead. Then, 51% say being Hispanic is a disadvantage, while 59% say that being white is an advantage. I wanted to start off with some statistics to use that as a guide as we talk about health care as related to these disparities.

Racial Microaggression

- President Clinton’s Race Advisory Board concluded that:

- Racism is one of the most divisive forces in our society

- Racial legacies of the past continue to haunt current policies and practices that create unfair disparities between minority and majority groups

- Racial inequities are so deeply ingrained in American society that they are nearly invisible

- Most White Americans are unaware of the advantages they enjoy in this society and of how their attitudes and actions unintentionally discriminate against persons of color

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271)

President Clinton's Advisory Board concluded that racism was one of the most divisive forces in our society, and the racial legacies that have preceded the current situation continue to haunt us and create a disparity in healthcare. They also reported that these inequities are deeply ingrained and quite invisible. And lastly, the most important part of all that you will see resonate throughout the presentation is that most white Americans are unaware of the advantages of simply being white. This sets the pace of why we are here today and talking about this.

I am going to just start off with terminology. It just seems like we have been talking about cultural competency for ages. During this time, there have been so many terms that have been thrown out.

Terminology

- Culture: “ the thoughts, communications actions, customs beliefs, values, and institutions of racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups”

- Race: refers to a person's physical characteristics, such as bone structure and skin, hair, or eye color

- Ethnicity: refers to particular social groups in complex societies, groups differentiated not only on the basis of a range of shared cultural content but also on the bases of social attitudes and economic and political considerations

- Ethnocentrism: evaluation of other cultures according to preconceptions originating in the standards and customs of one's own culture

- Racial Microaggressions: brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group

- Cultural Humility: “a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another's culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his own beliefs and cultural identities”

Culture is the thoughts, communication, beliefs, and values of a specific racial and social group. Race is the physical characteristics such as your skin color, et cetera. Ethnicity refers to a particular social group in a society based on a shared value or belief. It is also based on social attitudes, economics, and those all those aspects. Ethnocentrism is when we evaluate other cultures according to preconceived notions of our own. Racial microaggression is a newer term that I have seen in the literature. This is the understanding that there are brief and somewhat commonplace behavioral and environmental indignities that happen. Sometimes they are unintentional because people are used to speaking a certain way. However, they can have a very negative impact on a specific racial group. It is like a racial insult that is very subtle but can be very harmful. The last term, which we will go into a lot more, is cultural humility. Research shows that this term was coined in recent cultural competency literature. It is about reflecting on oneself, critiquing oneself, and really learning to be aware of what your biases and notions are.

What is an ...ism?

- “Isms” of any kind, often impose limits at the macro or societal level, on the groups affected, such as institutionalized or systemic limits of work, and social roles based on these “isms.”

(Grullon, E., et. al. (2018). A need for occupational justice: The impact of racial microaggression on occupations, wellness, and health promotion. Occupation: A medium of inquiry for students, faculty & other practitioners advocating for health through occupational studies, 3(1). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occupation/vol3/iss1/4)

Often we talk about cultural competency and get focused on race, but it is not always about race. Culture refers to various things, but in this presentation, we are going to focus on race. However, it is all about that "ism." I found this interesting in the literature. Isms are really a general term that refers to theory, practice, or doctrine. It describes something that really denotes the oppression of a group based on the characteristics of its members. Racism, sexism, and ageism are examples. It is anything that imposes limits on a macro societal level. We have already seen a lot of this in our health care literature.

Disparities in Healthcare

- Personal factors of care recipients, such as education, trust, compassion, respect, affordability, and cultural sensitivity, contributes to limited access to health care.

- Hispanics also report feeling disrespected by health professionals and this has generated a general distrust in the medical system (Cutts et al., 2016)

- Owen, Tao, Imel, Wampold, and Rodolfa (2014) believed people from diverse backgrounds experience microaggressions in all areas of life—including therapy and schools.

(Grullon, E., et. al. (2018). A need for occupational justice: The impact of racial microaggression on occupations, wellness, and health promotion. Occupation: A medium of inquiry for students, faculty & other practitioners advocating for health through occupational studies, 3(1). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occupation/vol3/iss1/4)

Are they really health disparities based on race? A lot of practitioners may not realize that there are or may not have given it consideration. Again, it might be under the radar of what you know, but the research shows there is indeed a significant disparity. Personal factors of our clients like education, respect, affordability, cultural sensitivity, and all of these aspects impact health care and accessibility. Culture is an essential part of health care accessibility and that creates a disparity right there. The research shows for example that Hispanics feel disrespected by health professionals all the time. This creates a general mistrust, which in turn creates a health disparity. Another research article in 2014 stated that people from diverse backgrounds experienced microaggressions in all areas of life, including therapy and schools.

- Hoffman et al. (2017) indicated medical students believed black skin was thicker than white skin thus having a higher pain tolerance

- Watson and Downe (2017) stated Roma women who are of darker skin, reported multiple cases of being mistreated, including poor communication; being abandoned; being physically and verbally abused; being refused care, and having to wait until non-Roma women were helped

(Watson, H.L., & Downe, S. (2017). Discrimination against childbearing Romani women in maternity care in Europe: a mixed-methods systematic review. Reproductive Health, 14(1).)

(Hoffman K.M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J.R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. PNAS, 113(16) 4296-4301)

Hoffman et al in 2017 indicated that medical students believed that black skin was thicker than white skin, and therefore presented a higher pain tolerance. It seems unbelievable that in 2017 medical students would have this archaic belief. Again in 2017, there was another article that reported that Roma women, indigenous women with darker skin, were being mistreated, not getting proper communication, abandoned, and even abused. These articles are quite eye-opening to see that this is still happening.

The Changing Face of Racism

- Contemporary racism share commonalities. They emphasize that racism:

- is more likely than ever to be disguised and covert

- has evolved from the “old fashioned” form, in which overt racial hatred and bigotry is consciously and publicly displayed, to a more ambiguous and nebulous form that is more difficult to identify and acknowledge

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

Racism is changing, and it is not the same. Everything evolves and that is part of life. Many studies in healthcare, education, employment, et cetera indicate that there is difficulty in describing and actually defining racism, and that is one of the hardest aspects of it. There is aversive racism or implicit bias, and it is hard to quantify. They are so subtle, somewhat nebulous, and of a very insidious nature. However, without this classification and understanding of these terms, it adds another layer of difficulty for practitioners like us. And, I do not think that it is something we can solve right away. However, it is important to understand what racism looks like right now, regardless of the various terms that are used.

Racism, contemporary-wise, is more likely than ever to be very covert. I am Indian by birth and grew up in England. Racism. in the 80s, when I was going to high school, was very overt at least in England. Now, there is the shift of being very covert where someone may not obviously say something to you, but outwardly, but they may imply it. It has evolved from the old fashioned form, where it was overt and very public, to more subtle which makes it so difficult to recognize and identify.

The Subtle But Significant Impact

- Daily common experiences of racial aggression that characterize aversive racism may have significantly more influence on racial anger, frustration, and self-esteem than traditional overt forms of racism.

- Furthermore, the invisible nature of acts of aversive racism prevents perpetrators from realizing and confronting:

- their own complicity in creating psychological dilemmas for minorities

- their role in creating disparities in employment, health care, and education

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

It is subtle, but that does not mean that it is not impactful. "They are not saying it to your face so do not worry about it." Well, the literature shows that common daily experiences of these subtle racisms or racial instances actually are considered aversive racism and have significantly more influence on racial behaviors. It impacts the person receiving this in a very significant way. Furthermore, these invisible insults or subtle racism encounters have major issues. For one, it prevents the perpetrators from realizing and confronting their own problem with racial issues and their practice and their role in how they are creating this disparity in health care. This ends up impacting everyone globally. It is a butterfly effect. I am not really recognizing what I am doing but then that builds up and causes a greater effect.

Forms of Microaggressions

Macroaggressions take many forms:

- subtle, stunning, often automatic, and non-verbal exchanges which are ‘put-downs’

- “subtle insults (verbal, non- verbal, and/or visual) directed toward people of color, often automatically or unconsciously”

- brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to people of color because they belong to a racial minority group

- are not limited to human encounters alone but may also be environmental in nature

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

There are several forms of micro-aggression. As I said, they are subtle, automatic, put-downs. They can also be non-verbal. It can be framed as a joke. These are subtle insults directed towards people of color. They can also be automatic and not conscious. They can be brief, everyday exchanges that are towards a minority group. These are not limited to human encounters like verbal exchanges and behaviors, but they also are environmental. For example, if I go to see a counselor and all of the literature is based on Caucasians or the posters I see in the waiting room are all Caucasian, it may not be an overt thought, but I may think that this is not the right counselor for me. It might appear based on the environment that she does have a lot of exposure to my type of people or my background. This may be an assumption I might make as a client.

Three Types of Microaggressions

- Micro-assault: old-fashioned racism “colored” or “oriental”. Generally expressed in limited “private” situations (micro) that allow the perpetrator some degree of anonymity.

- Micro-insult: represent subtle snubs, frequently unknown to the perpetrator, but clearly convey a hidden insulting message to the recipient of color. Can be nonverbal.

- Micro-invalidations: are characterized by communications that exclude, negate, or nullify the psychological thoughts, feelings, or experiential reality of a person of color. Don’t be so oversensitive” or “Don’t be so petty,

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271)

There are three types of microaggression. Micro-assault is old fashioned racism. For example, you might call someone colored or oriental. Generally, this happens more in private situations, and hence micro. The thing about it is the perpetrator can be anonymous. The perpetrator has the advantage. Micro-assaults are more overt, while micro-insults are more subtle snaps and are hidden. They are conveyed but not very directly. An example might be when a white employer tells a candidate of color, "I believe that the most qualified person should get the job regardless of race." Or, when the employee of color is asked, "How did you get your job?" The underlying message from the recipient may be that all people of color are not qualified. Micro-invalidations are characterized by communications that exclude or negate the feelings of someone who might be experiencing in their mind racial microaggression. "Do not be so over-sensitive." "Do not be petty." "It is all in your head." I can tell you as a therapist of color, I have definitely experienced that. These three forms are really important to understand because they really are very inherent in our society right now and are extremely insidious and detrimental to practice.

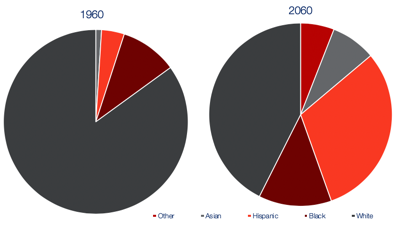

9 Versions of Microaggressions

- Alien in Own Land

- A belief that visible racial/ethnic minority citizens are foreingers

- Color Blindness

- Denial or pretense that a White person does not see color or race.

- Myth of Meritocracy

- Statements which assert that race plays a minor role in life success.

- Denial of Individual Racism

- Denial of personal racism or one’s role in its perpetuation.

- Ascription of Intelligence

- Assigning a degree of intelligence to a person of color based on their race.

- Second Class Citizen

- Treated as a lesser person or group.

- Pathologizing cultural values/communication styles

- The notion that the values and communication styles of people of color are abnormal.

- Assumption of Criminal status

- Presumed to be a criminal, dangerous, or deviant based on race.

- Environmental Microaggressions

- Macro-level microaggressions, which are more apparent on systemic and environmental levels.

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271)

There are nine versions of micro-aggressions that the literature defines. Let's start with an Alien in Own Land. This is the belief that a visible racial minority, even though they are citizens, are actually foreigners. While I am a citizen, many people still see me as a foreigner because I am not white and my accent is not very American. Number two would be Color Blindness. This is when you say, "I do not see color." You may or may not, and I am not here to defend that. It is about being aware of what you may not be aware of. The third is the Myth of Meritocracy. These are statements that assert that race plays a minor role in life success. The Denial of Individual Racism are statements such as, "I am not racist at all because I have a friend who is African American." Or, "I have a friend who is Indian." Ascription of Intelligence is something that happens all the time. I can speak to it firsthand because I am Indian. People assume that I am good at science. That is a general assumption. Second class citizen is where a person is treated as a lesser person of a group. Pathologizing cultural values and communication styles is the notion that values and communication styles of people of color are not typical or abnormal, for example. The Assumption of Criminal Status is that because you are in a specific ethnicity you might be more prone to criminal activities. Lastly, environmental microaggressions that are more apparent happen in a more systemic way. An example would be the doctor's office with pictures of all one race as an example.

How Serious is This?

- The experience of a racial microaggression has major implications for both the perpetrator and the target person

- It creates psychological dilemmas that unless adequately resolved lead to increased levels of racial anger, mistrust, and loss of self-esteem for persons of color; prevent White people from perceiving a different racial reality; and create impediments to harmonious race-relations (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004; Thompson & Neville, 1999)

Is it really that serious? We know that health disparities are not good. Microaggressions have major implications for both the perpetrator and the targeted person. The person who is actually committing the racial microaggressions may not realize it. That is very harmful to them as well. The literature shows that it creates psychological dilemmas, that unless they are adequately resolved, lead to increased levels of frustration, stress, mistrust, and generally not a good feeling. It creates bad karma between races and society in general.

What Are Therapists' Responsibilities?

- Practitioners have an opportunity to play a vital role in addressing issues of occupational injustice promoted by acts of micro-aggression

- Furthermore, as Aldrich et al. indicate in their 2017 article, occupational therapists in the U.S. have yet to take on the responsibility of addressing occupational injustices within their practice

(Arnold, M. J., & Rybski, D. (2010). Occupational justice. Occupational therapy in the promotion of health and wellness (pp. 135-156). Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.)

What are our responsibilities as therapists? As practitioners, we have an opportunity to play a vital role. Specifically, we want to address occupational injustice which is promoted by acts of microaggression. Occupational injustice happens when participation in an occupation is bought, segregated, prohibited, or restricted in any way. Our goal is obviously to improve participation and quality of life for our clients. Thus, if we are not addressing these microaggressions, we are inherent in contributing to it. I think this is what the article by Aldrich et al. (2017) was saying. Occupational therapists in the US have yet to take on this responsibility of decreasing occupational injustice in practice. White therapists may not be aware of what you are not aware of, and there is definitely a power dynamic going on.

Prejudice, Privilege, and Power

When I looked at the literature, prejudice, privilege, and power are the three main areas that are limiting our progress in cultural competency. Professional power, white privilege, and biases are the three-tiered problem.

Figure 2. A three-tiered problem in cultural competency.

Power hierarchies are present between clinicians and their patients. If you look at a traditional relationship between a patient and a provider, it tends to be very paternalistic. The provider is directing the patient on a treatment plan. You need to do x, y, and z to mitigate a health concern. However, a balanced approach to this would be a shared patient and a provider relationship with shared decision making. We make the decision based on clinical expertise, but also consider the patient's lifestyle needs, values, and preferences.

Examples of Professional Privilege and Control

- Direct Coercion: actual control over clients’ bodies or health care interactions (via restricted movement to prevent falls, forced medication, etc.)

- Ideologic hegemony: more nuanced and subtle; it may involve pressuring clients to change their behaviors or make specific choices based on what the provider deems is necessary or good

- Inevitably, these perspectives are culturally informed, and they are not necessarily negative

(Agner J. (2020). Moving from cultural competence to cultural humility in occupational therapy: A paradigm shift. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(4).)

I wanted to share some examples of professional privilege and control The first is direct coercion. An example is when you are in a position of professional privilege, like an OT and the considered expert. We would definitely do some things that may be perceived as direct coercion. For example, if a patient is having pain, I might say, "I would like you to do these exercises to eliminate the pain." There is an example of direct coercion because I have not taken into account the environmental or cultural situation. Instead, I have said, "This is what you need to do to get rid of the pain." I am forcing them to do these activities in a way to achieve the goal they want.

Then there's ideologic hegemony. This is more nuanced and subtle. This may involve pressuring clients to change their behaviors or make specific choices based on what the provider deems is necessarily good. Perhaps I see a client who wants OT but does not have a car. She has to borrow a car and come to therapy for her child. If she cancels, I might get upset at her and I say, "Well, we cannot continue because you cannot make the sessions." Am I really understanding her position and taking into account what is going on? These two aspects can be hard to understand.

Honestly, when I was reading the literature, it was really hard to tease it apart. The important thing to remember is that these perspectives are culturally informed, and they are not necessarily negative. If a client does not bring in their child to therapy, for whatever reason, my intention is not negative. It is true that I cannot help your child if you do not show up, but we just need to make sure that we address any subtle nuances.

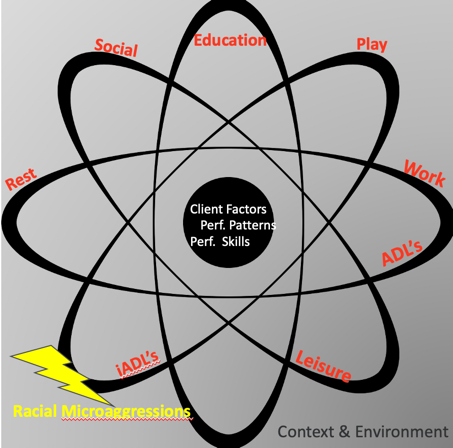

Using the OTPF as a Guide

Let's use the OTPF as a guide as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF).

The client is in the center with their factors, performance patterns, and their skill set. On the outside are the domains of occupational therapy and the aspects we address. These are social, education, play, work, ADLs, IADLs, leisure, and rest. How does this all apply within the context of racial microaggressions? What client factors, for example, might be impacted when there are some racial issues going on? Are you as a therapist considering these? Context and environment are also pertinent in this model. Thus, if you are only looking at the center and addressing client factors while disregarding the context and environment, then there will be a disparity in your delivery of health care.

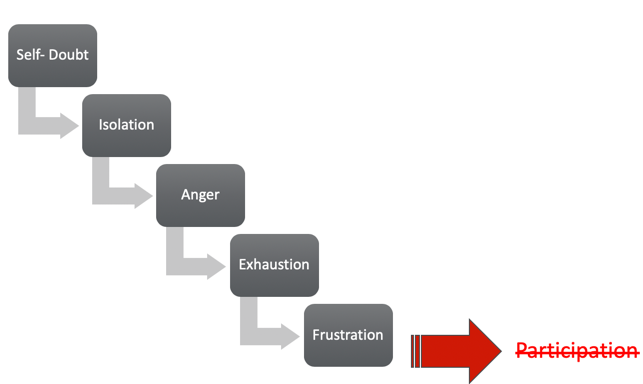

As the literature indicates, racial microaggressions have a very significant impact that may not be apparent to you and me. They can be very subtle, but they create self-doubt, isolation, anger, exhaustion, frustration, and it really does impact overall participation, a core topic for us in OT. Let's look at some of these racial microaggressions. But before I go there, I do want to talk about stress in general. I can tell you that stress is a very key component of racial microaggression. It is very important to acknowledge any stress you have or that your client has experienced due to microaggressions. We have to think about stress in the same way as we think of something that has physically happened in the environment. Stress is our response to the conditions of stimuli in the environment. So if a client is experiencing stress, you need to look at the environment to see what is going on.

There are several types of stress that are encountered. There is tolerable stress, and then there is a toxic or stress response. Positive stresses are fairly normal and healthy. An example is when you are about to do a presentation. You get butterflies in your stomach. This type of stress makes us alert. We need this for long-lasting events. Toxic stress happens when we have strong, frequent, and prolonged adversity in our lives. Stress is a really important part when we are considering the participation of clients. Figure 4 is a schema of this.

Figure 4. Stress and participation.

Impact of Microaggressions on ADLs

- Studies investigating the importance of sleep and the factors that reduce sleep in individuals who experienced high levels of discrimination found that shorter periods of sleep were associated with increased risk for depressive symptoms and vulnerability for these individuals, thus influencing their overall health and wellness.

(Dunbar, M., Mirpuri, S., & Yip, T. (2017). Ethnic/racial discrimination moderates the effect of sleep quality on school engagement across high school. Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology, 23(4), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000146)

How do racial microaggressions impact ADLs? Studies show that individuals who have experienced discrimination, have reduced sleep. This, in turn, impacts their everyday living activities. IDLs, leisure, and play.

Impacts of Microagressions on IADL of Child Rearing

- African Canadian women have had concerns about raising their children to 'deal' with racism & media in the past few months, to develop occupational roles as parents that include teaching coping strategies to their children to combat racism.

- Microaggressions experience of past generations have created additional responsibilities for African-Canadian parents

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

There is an impact on child-rearing. I saw articles where African Canadian women were dealing with racism with child-rearing. In addition to worrying about driving and texting and other typical child-rearing activities, they were also worried about race. "Make sure that you do not say anything wrong," or "Don't drive there."

Impact on Leisure

- Everyday forms of racism impacted leisure activities such as watching television, going out to dine, etc. amongst African-American and African-Canadian women who participated in their studies

- African-American customers disclosed they were often monitored, scrutinized, and being ignored and belittled when shopping

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

It also impacts leisure. If you feel snubbed in any way, you may choose to not do that particular activity. We want to do things that make us feel good. If I hang out with my friend and her sister and the sister keeps making subtle comments that are racist, am I going to want to hang out with her again? This is going to have an impact on me. The research shows that African Americans and African Canadian women avoided activities like watching TV or going to restaurants because of these microaggressions. Also, African American women stated that they were monitored and scrutinized more. There are some videos on YouTube that highlight this.

Barriers of Racial Microaggressions in Practice

How does racial microaggression impair our therapeutic alliance? There are several barriers and the first one I already identified which is the environment. If you have a therapeutic clinic, you can have diverse brochures and pictures as examples.

- For effective therapy to occur, some form of a positive coalition must develop between therapist and client: therapeutic alliance

- Findings that a client’s perception of an accepting and positive relationship is a better predictor of a successful outcome than is a similar perception by the counselor

- Clinical practice microaggressions are likely to go unrecognized by White clinicians who are unintentionally and unconsciously expressing bias

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271)

For effective therapy to occur, there has to be a therapeutic alliance. A therapeutic relationship is the most important part of what we do with our clients, especially when they come from a different race or have different values. White therapists are products of their cultural conditioning. This is why when we look at the therapeutic alliance, it tends to focus more on white therapists. This therapeutic alliance is likely to be weakened or terminated when clients of color perceive therapists to be prejudiced, biased, or unlikely to understand them. It has been postulated that a therapist bias may account for the low use of mental health services and premature termination of therapy by minorities. Thus, it is really important that we understand what the client's perceptions are and understand that there might be some microaggressions we are not recognizing.

Examples of Racial Microaggressions in Therapeutic Practice

Now, we are going to go through all the examples of microaggressions in therapeutic practice. If you are interested in this, please do read the article cited below as it is brilliant. This is where I got most of this literature for therapeutic alliances.

This particular case study was highlighted in this journal. Two colleagues, an Asian American and an African American, were flying from New York to Boston on a small plane with a single row of seats. When they got on the plane there were not many passengers. The flight attendant told them to go ahead and sit anywhere. They sat in the front across the aisle from each other. Three white men in suits then entered the plane, and they were informed they could also sit anywhere. They sat in front of the Asian and African American colleagues. To space out the passengers and weight on the plane, the flight attendant asked the African American and Asian American colleagues if they would mind moving to the back. Upon this request, both the passengers of color had a negative reaction. First balancing the weight, it certainly seems reasonable, but why would they be asked to do that when they boarded the plane first? They asked her, "Why did you choose us? It feels like you chose us because we are people of color. It felt like you were asking us to go to the rear of the bus, so to speak." The flight attendant was horrified. She said, "I have never been excused of that. How dare you, I do not see color. I only asked you to, distribute the weight." I want you to keep this scenario in mind as we go through this. In this situation, it is very hard to tell who is right and wrong because there is really no way to know. A lot of people of color have this doubt in their minds. Am I really hearing this am I not? This itself can be very detrimental. As I said, we will go through it more again, but before we do that I want to go through racial microaggressions in practice

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

Example 1: Alien in Own Land

Figure 5. Alien in Own Land example.

The first example is a white client that does not want to work with an Asian American therapist because she does not feel like she would understand. Or, a white therapist tells a Latino client that she should seek a Spanish speaking therapist. The message is, "You are not American." I have experienced this myself where a white parent did not feel that I understood the culture in early intervention for her and her baby. I certainly felt that microaggression.

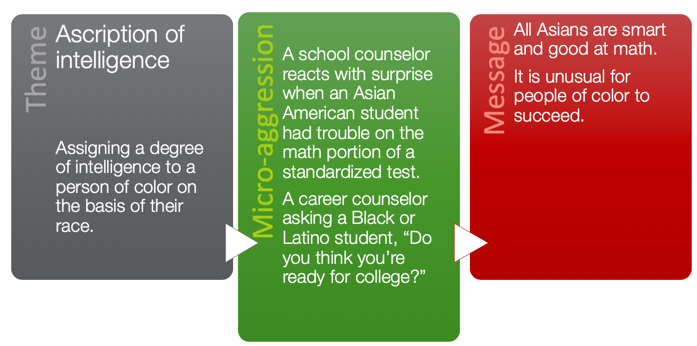

Example 2: Ascription of Intelligence

Figure 6. Example of Ascription of Intelligence.

We talked about this before about assigning a degree of intelligence based on race. I get told all of the time, "You must be good at science," or, "You must be good at math because you are Indian."

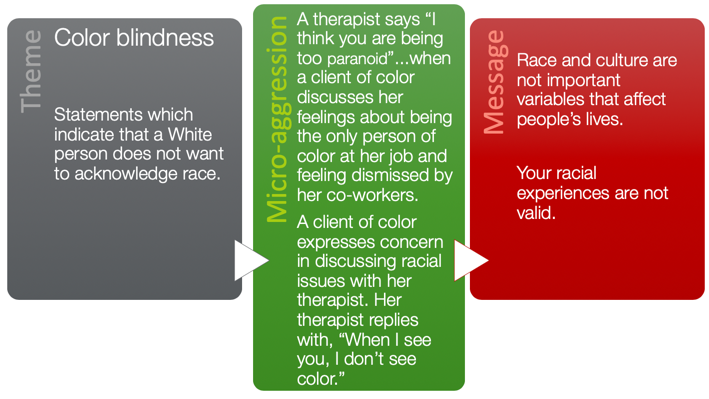

Example 3: Color Blindness

Figure 7. Example of color blindness.

Then, we have color blindness. This is very prominent in therapeutic practice. Referring back to that airplane situation, the flight attendant was also inferring that the clients or the patrons were being paranoid. In a therapeutic setting, a therapist might tell a client of color that they too are paranoid when they discuss their feelings. This happens often because we do not want to deal with the conversation. This does not have to be an aversive situation. The message they are getting is that race and culture are not important variables that impact people's lives, and that their racial experiences are not valid. Instead of doing that, it is better to ask them why they felt that way. "Yes, I can certainly see how you would perceive that."

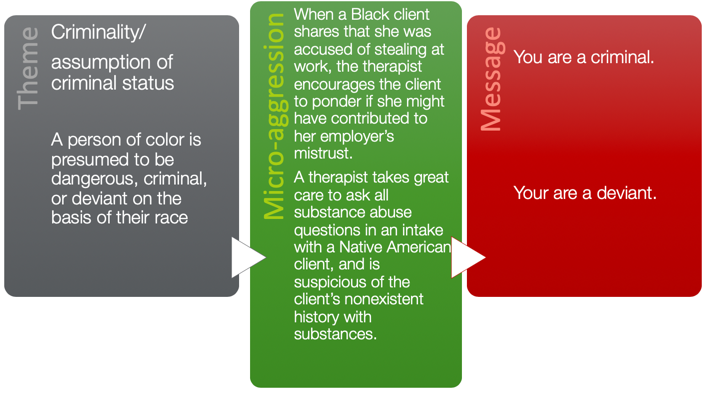

Example 4: Criminality

Figure 8. Example of criminality.

Criminality is pretty obvious, I think this is probably the most common and overt of them all. For example, a client may share that when she was accused of stealing at work, the therapist encouraged this client to ponder if she may have contributed to the employees' trust by doing something or saying something. Or, a therapist takes great care to ask all substance abuse questions in intake with a Native American client and is suspicious of the client's nonexistent history with substances. Again, this is a very subtle nuance. Your knowledge of what you think Native Americans do and believe may make you question whether they are telling the truth. The message becomes that you are likely a criminal in the first situation, and you are a deviant in the other one.

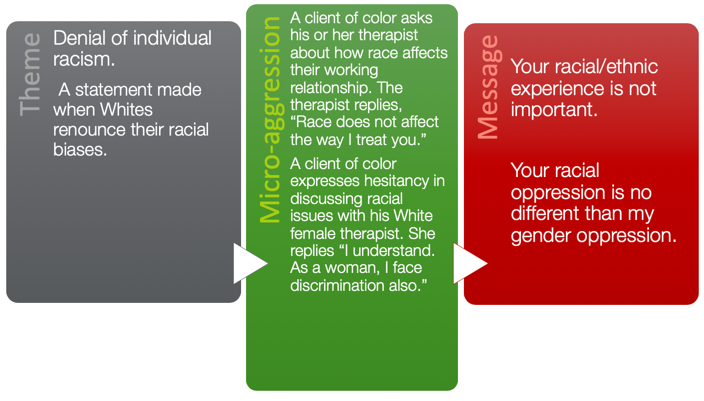

Example 5: Denial of Individual Racism

Figure 9. Example of Denial of Individual Racism.

Denial of individual racism is when whites renounce their racial biases as an example. A client of color asks his or her therapist about how race affects their working relationship, and the therapist says, "Race doesn't matter at all. I treat you the same." The message you are giving is that racial and ethnic experience is not important. That is really interesting, isn't it? We mean that we are not intending to treat them any differently, but the reality is, everyone comes from a different experience and different background, so race and ethnicity do play a role here. Instead of saying that, it might be better to say, "I consider an individual person's values, beliefs, and experiences. I try not to assume and instead try to ask what a client's values are so that I am treating everybody fairly regardless of their color."

Another example is that a client of color expresses hesitancy in discussing racial issues with his white female therapist. She replies, "I understand because as a woman, I have faced discrimination as well." The message you are giving is that your racial oppression is no different than my gender oppression. Oppression has some commonalities there is no doubt, but equating your experience with somebody else's that may be a little bit difficult for the recipient as there are different degrees and situations. Instead, you can say, "I may have some understanding of what you have been through, but I certainly am not in your shoes and cannot tell to what degree it has impacted you."

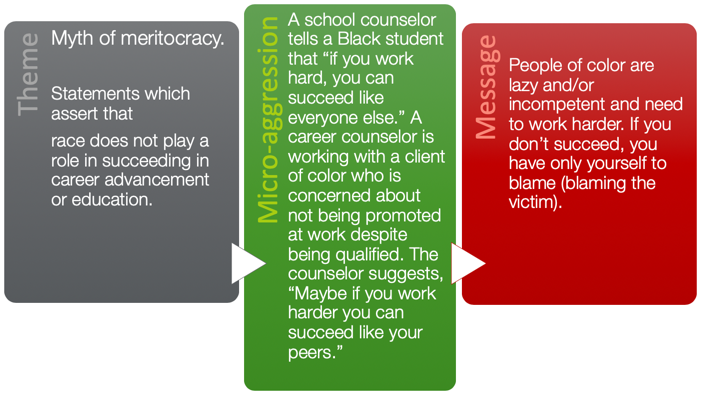

Example 6: Myth of Meritocracy

Figure 10. Example of Myth of Meritocracy.

The myth of meritocracy are statements that assert that race does not play a role in career advancement. For example, a school counselor tells a black student that if you work hard, you can succeed like everyone else. Or, a career counselor might say, "If you worked harder, you can succeed like your peers." The message we give them here is people of color are lazy, or incompetent, or need to work harder. We need to be careful. "You are not doing the exercises as I requested," You have not done the recommended homework," are two more examples. We do not want this to appear to be based on race.

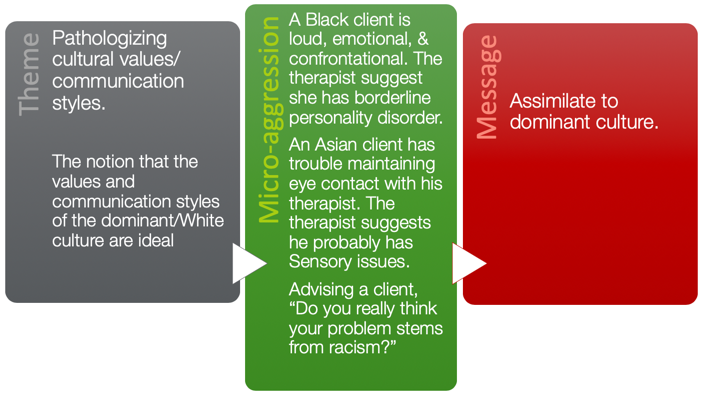

Example 7: Pathologizing Cultural Values/Communication Styles

Figure 11. Example of Pathologizing Cultural Values and Communications Styles.

This is the notion that values and communication of the white or dominant culture are ideal. For example, a black client may be loud, emotional, or confrontational, and it is suggested that they have a borderline personality disorder. An Asian client may not make eye contact, and it is assumed that she has sensory issues. However, perhaps this was how she was brought up. You need to assimilate to the dominant culture is the message you are giving. And, if you do not assimilate, then you are not good enough.

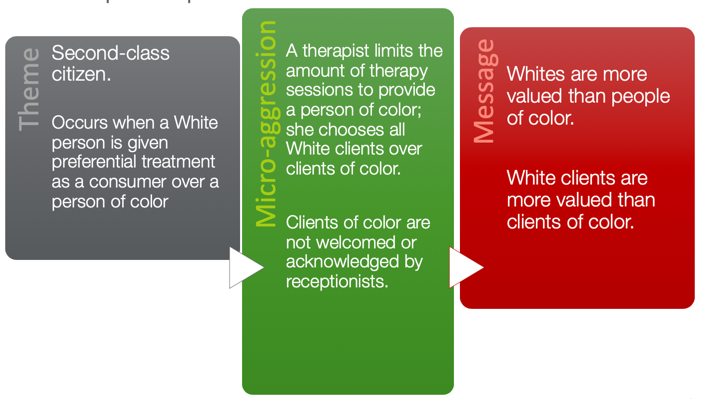

Example 8: Second Class Citizen

Figure 12. Example of Second Class Citizen.

This is when a white person is given preferential treatment over a consumer based on color. We have heard a lot about this. In a therapeutic environment, a therapist might limit the number of therapy sessions for a person of color. For example, if a therapist is providing early intervention home services to a family of color in a poor neighborhood, they might discharge services or suggest just reducing the frequency. Clients of color may not be welcomed or acknowledged by the receptionist as compared to a white patron. Again, we have to be very careful with the message we are sending.

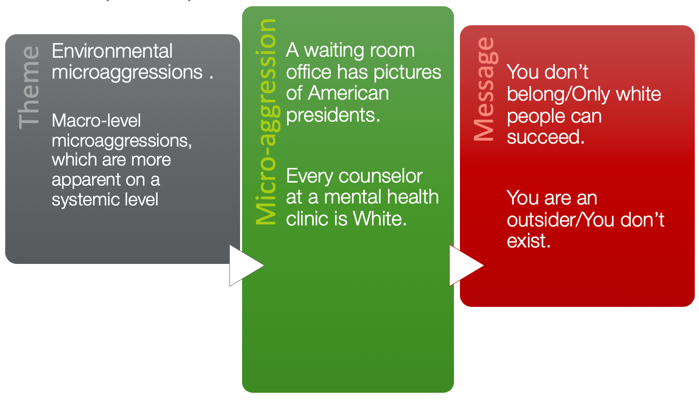

Example 9: Environmental Microaggressions

Figure 13. Example of Environmental Microaggressions.

Example 10 looks at environmental microaggression. An example would be not much diversity on staff. We do need to consider on a macro level that are we representing the cultural landscape that is up and coming in healthcare.

Dilemmas

If we go back to our story about the flight attendant and the two patrons of color. I just want to talk about some of the dilemmas, because these are very apparent in that situation and can be applied to the therapeutic setting.

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

Dilemma 1: Clash of Racial Realities

- Studies indicate that the racial perceptions of people of color differ markedly from those of Whites

- White Americans tend to believe that minorities are doing better in life, that discrimination is on the decline, that racism is no longer a significant factor in the lives of people of color, and that equality has been achieved

- The majority of Whites do not view themselves as racist

96% of African Americans reported experiencing racial discrimination in a one-year period (Klonoff & Landrine, 1999), and many incidents involved being mistaken for a service worker, being ignored, given poor service, treated rudely, or experiencing strangers acting fearful or intimidated when around them.

The question we posed is, "Did the flight attendant engage in microaggression, or did the patrons of color and his colleague just misinterpret the action?" How do we know? There is no right answer because everyone has their own perception. The literature shows that the racial perceptions of people of color differ remarkably from those of whites. Your perception may very different than mine, while mine may be very different than someone else as we have all had different life experiences. However, the literature also shows that white Americans tend to believe that minorities are doing better in life and discrimination is on the decline. I had a client once who said to me when Obama was president, "I am sure you are happy that there are not as many racial issues. She believed that things were better because there was an African American president. And, the majority of whites do not view themselves as racist. I believe that this client had absolutely no thought whatsoever idea that she was being racist or making insensitive comments. She was a lovely lady who just said what she thought.

It is important for us to know that 96% of African Americans report that they have experienced racial discrimination, and in many instances, they have been mistaken for a service worker, have been ignored, were given poor service, treated rudely, and experienced major issues when they were shopping. I am going to share an experience that I had. I am married to a man that is half Indian and half white, but he looks white. When I took my kids to a swim class, there was a Latino lady with her child. She looked at me and she said, "How long have you been taking care of them?" I said, "Since they were born." She assumed that I was the help because of the color differentiation between my kids and me. This clash of racial reality is apparent in the real world and in practice.

Dilemma 2: The Invisibility of Unintentional Expressions of Bias

- Considerable empirical evidence exists showing that racial microaggressions become automatic because of cultural conditioning and that they may become connected neurologically with the processing of emotions that surround prejudice

The second dilemma is the invisibility of unintentional expressions of bias. The flight attendant's actions were invisible to her. She had no idea what she was doing, or that it could have been construed that way.

- How does one prove that a Microaggression has occurred?

- Microaggressions:

- Tend to be subtle, indirect, and unintentional

- Are most likely to emerge not when a behavior would look prejudicial, but when other rationales can be offered for prejudicial behavior

- Occur when Whites pretend not to notice differences, thereby justifying that “color” was not involved in the actions taken

- Microaggressions:

There is considerable empirical evidence that shows racial microaggressions do become automatic because people experience cultural conditioning. They become connected neurologically with the processing of emotions that surround prejudice. That really is a profound statement that it changes our neurological connection in the brain. Microaggressions are that detrimental. How does one actually prove that microaggression has occurred? In that situation with the flight attendant, it was so subtle, indirect, and unintentional. If those patrons of color felt slighted, how do they even prove that? That is very difficult.

Dilemma 3: Perceived Minimal Harm of Racial Microaggressions

- The perpetrator usually believes that the victim has overreacted and is being overly sensitive and/or petty

- People of color are told not to overreact and to simply “let it go”

- A conspiracy of silence

Microaggressions and that their effects are cumulative, it becomes easier to understand the psychological toll they may take on recipients’ well-being.

In most cases when individuals are confronted with micro-aggressive acts like in the story of the flight attendant, the perpetrator typically believes that the victim is overreacting. She inferred that they were overreacting and being petty and oversensitive. Now, this changes how minorities psychologically perceive themselves. When I have a racial encounter, I do doubt myself and wonder if I am being petty or silly. We have this cultural belief that we should just let it go. However, the evidence also supports that the detrimental impact of more subtle forms of racism are very detrimental not only to the perpetrator but also to the recipient because it is this perception of minimal harm. Researchers have also found a positive association between happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem, mastery of control, overall general health, and discrimination. So, it does take a toll on a recipient's and the perpetrator's well-being.

Dilemma 4: The Catch-22 of Responding to Microaggressions

- The person must determine whether a microaggression has occurred.

- How one reacts to a microaggression may have differential effects, not only on the perpetrator but on the person of color as well.

- Responding with anger and striking back (perhaps a normal and healthy reaction) is likely to engender negative consequences for persons of color as well.

The fourth dilemma is that the person must determine if a microaggression is happening. There is no way to know if it is deliberate, unintentional, or how to respond. Should I just bring it up, or should I just let it go? People of color rely heavily on experience to decide what to do in these situations. I have brought up things in the past, and it has become a big issue. Then, I might not bring it up again. Responding with anger, striking back, and all those things can have a lot of negative consequences. It really depends on you as a person and your experiences.

Where Do We Go From Here?

- Greatest challenge society and health professions face are “making the ‘invisible’ visible”

- Education and training is critical

- Studies suggest that White clinicians receive minimal or no practicum or supervision experiences that address race and are uncomfortable broaching the topic with trembling voices, and mispronunciation of words when directly engaged in discussions about race

Where do we go from here? This is really difficult because we do not know when we are being aggressive or creating a racial microaggression because sometimes it is so subtle and unintentional. The greatest challenge in society and that health professionals face is making the 'invisible' visible. The literature shows that education and training are critical. Additionally, they suggest that white clinicians are not receiving any supervision experiences or education that address this. They are afraid of talking about it, and they are afraid to bring it up. It might be that sometimes it leads to politics and other personal topics. We do have to address race in the environment of healthcare, especially within OT, because it impacts participation.

Cultural Competency Programs & Racial Microaggressions

- Must support trainees in overcoming their fears and their resistance to talking about race

- Promotes inquiry and allows trainees to experience discomfort and vulnerability

- Understanding how microaggressions, especially those of the therapist, influence the therapeutic process

- Self-awareness: What does it mean to be white?

- Notice a shift away from knowledge-based training

(Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.)

We have been talking about cultural competency for ages. We know we need to address it, and there are many models that have been developed. Many show that education is a key component. We need to educate our professors and students to make them understand it is a problem. However, if we are truly going to address culture in the healthcare field, we need to support trainees to overcome their fears of just discussing it.