Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Patient-Centered Strategies to Managing Geriatric Chronic Pain in Home Health, presented by Olaide Oluwole-Sangoseni, PT, PhD, DPT, MSc, GCS.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the mechanism of chronic pain.

- Identify at least three common issues, including cross-cultural sensitivities, facing home health PTs and PTAs in the management of chronic pain.

- List at least three causative factors of chronic pain with evidence-based screening tools.

- Outline at least three evidence-based interventions for geriatric chronic pain in home health.

Introduction and Overview

Thank you for your participation today on the topic of managing geriatric chronic pain in home health. Many home health providers indicate that their patients' top complaints center around pain*. Providers report complaints such as loss of mobility due to pain, inability to sleep due to pain, and unmanageable pain after surgery. Additionally, pain can interfere with activities of daily living and cause fatigue. Due to the opioid epidemic in society today, we are moving away from prescribing medicine to relieve pain, and toward physical therapy interventions to manage pain. In this presentation, we will delve into geriatric issues related to chronic pain in the home health setting, including cross-cultural and causative factors, as well as evidence-based interventions for pain management.

(*Based on participant responses gathered from a poll taken during the live event.)

What is Pain?

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience primarily associated with tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage, or both." Tissue damage doesn't necessarily have to be present in order for a person to have a complaint of pain. However, tissue damage may be present and the person will have pain. In some cases, there is tissue damage but there is no pain.

As therapists, we understand that pain may be an emotional experience whether in the presence of tissue damage or not. Pain has both physical and psychological components. Pain can be seen as a protective warning or signal of actual or potential tissue damage. Furthermore, pain is a subjective perception that damage has occurred or that damage may occur. It's like you have yellow tape surrounding the tissue or a body part, and your neurophysiological system is trying to warn you. Levels of pain that your patient describes may be a combination of nociception and interpretation of its emotional significance by the pain centers in the brain.

Pain Signaling Process

How does nociception relate to pain? In order for us to understand that relationship, we have to look at detection and signaling. If my body systems detect pain, how will they inform me that it is pain? Pain detection and pain signaling involve a chain of events starting from the nociceptors. Nociceptors are free nerve endings that detect potentially damaging stimuli, whether it be mechanical, thermal, chemical, electrical or any source of stimulation that may be damaging. As long as the stimulus leads to the development of action potentials, the pain signal will be raised, and nociceptors will start firing. The action potential goes through what is known as the first order. Alpha, Delta, and C fibers connect to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and then go through all the way through the spinothalamic tract before getting to their destination in the brain. Why is that important? This nociceptive input leads to the activation of the sending inhibitory pathways to decrease the intensity of pain perception. That's why the degree of pain described by your patient is a combination of nociception and interpretation of what that nociception means. The anterior cingulate gyrus of the cerebral cortex interprets what you felt as pain. That's the difference between pain and nociception. Nociception has to develop action potential. The brain has to recognize that it is strong enough and interpret it as pain.

Prevalence

More than 76 million people in the United States experience pain according to the International Association for the Study of Pain. The incidence of pain peaks in the age range of 45 to 64 years and declines in older populations. That being said, older adults have a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions with persistent pain. There is an increased prevalence of articular weight-bearing joints in people over 65 years of age, as well as osteoarthritis of their weight-bearing joints, which is considered "wear and tear". Most of the patients that we see in home health are over 65 years of age. To reiterate, sometimes there is damage but there is no pain, sometimes there is pain with damage, and sometimes there is pain without damage. The fact that they have OA doesn't necessarily mean that the OA is the cause of the pain, but it may be.

According to the US Office of the Inspector General, in 2016, 33% of Medicare Part D recipients (approximately 500,000 people) received opioid prescriptions. Based on these numbers, they project that the misuse of opioids is likely to double or triple. They also gathered information to indicate that 10% of deaths in past years were due to opioids. In fact, life expectancy in the United States has significantly decreased in recent years. Between 2014 to 2015, life expectancy in the US decreased by .28. People are not living as long as they used to because of misuse of prescription pain medicine. As such, people are beginning to turn to physical therapy as an alternative to pain medicine

Multiple Mechanisms of Pain

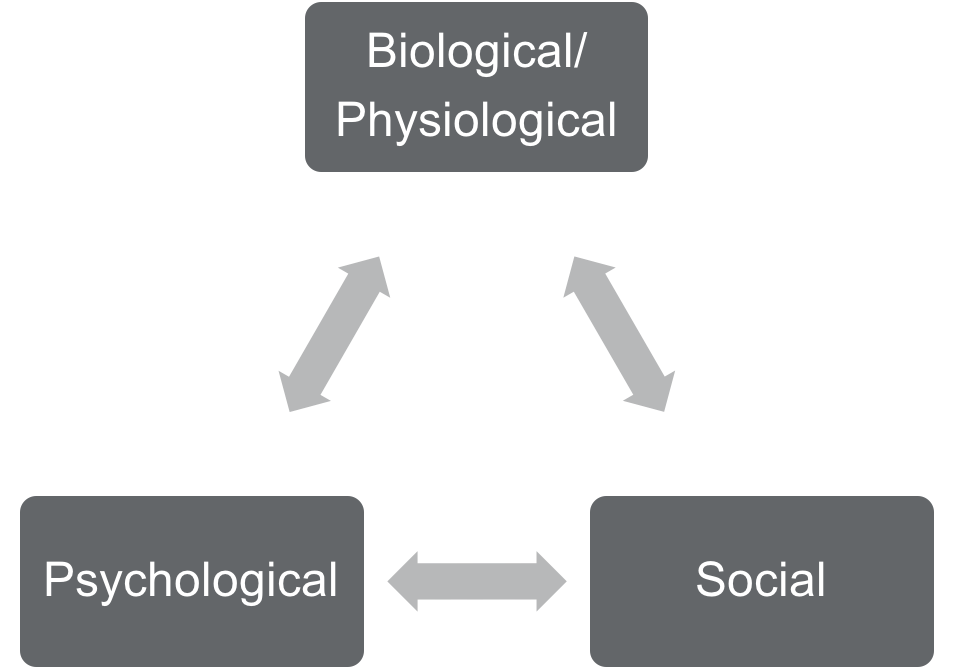

The sensitivity of pain is a panoply of factors because there is a cascade of events taking place. Pain is complex and heterogeneous, as multiple mechanisms are interacting which contribute to the onset of pain and the prolonged experience of pain, also known as persistent pain. The mechanisms may be biological/physiological, psychological, and social, and they all interact with each other (Figure 1). It's this interaction that makes pain complex. It's this interaction that takes out the homogeneity of pain and makes it heterogeneous.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of pain.

Quality of Pain

Since pain is so complex, it can be described by the quality or type of pain a person is experiencing. With regard to quality, a person can experience pain as a physiological event or as a psychological experience. When pain is a physiological event, the body is dependent on subjective recognition. When pain is a psychological experience, pain can occur in the absence of tissue damage. However, chronic pain has a combination of both physiological and psychological elements that interact. If a person's pain has a combination of both physiological and psychological elements, it has the potential to affect their social life. How I perceive my pain is going to affect how I relate to people. A person in pain may think the following thoughts: "I don't want to be a bother. When I'm in pain, I don't want to talk to anyone. When I'm in pain, I feel depressed. When I'm in pain, I am sleepless and tired all the time." We have to look at pain as not just a straight linear line, but at the interaction of all those components. Science has shown that pain, whether in old or young people, has a cognitive component. As we're going to see later, it's especially inflated when it comes to older adults.

Sometimes the psychological element of pain trumps the physiological because pain is an emotional experience. It's unpleasant and uncomfortable. Pain can change a person's mood from happy and agreeable to angry and irritable. That's the emotional, sensory aspect of it. Evidence suggests that we have to pay attention to that psychological element. We don't have a choice. With the physiological element, there is a structural component to that in the neurochemistry and the function of the peripheral and the central nervous system. That's what feeds the psychological element. Then, since the pain is so persistent and unpleasant, the psychological goes back and has an impact on the physiological, changing our neurochemistry.

In addition to the qualities of pain, we can further describe pain as either being a disease process or an illness process. The disease process involves the nociceptors that we talked about previously, and it involves the processing of pain by the central nervous system. This means that there are changes in the structure of the alpha, delta fibers, and the nociceptors' ability to detect potentially damaging stimuli. They are hyperstimulated, and there are changes in the structure, neurochemistry, and function of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and the central nervous system (CNS). In contrast, with regard to the illness process, there is a change in behavior. The illness component of pain is indicative of changes in behavior and the suffering that is associated with pain.

In summary, we defined pain as an unpleasant sensory-emotional experience primarily associated with tissue damage. It's also a protective warning signal of actual or potential tissue damage. There is a subjective aspect to pain. There are psychological, physiological, disease and illness components to pain. Taking all of these elements of pain into consideration, when working with patients, it is important to understand that pain is whatever your patient says it is. Each patient's perception of their pain will be different and valid.

Socioeconomic Factors

There are socioeconomic factors that impact or affect how pain is perceived. These socioeconomic factors fall into two categories: passive coping strategies and active coping strategies.

Passive coping strategies. Passive coping strategies are highly utilized by older adults. You may also see passive coping strategies in those with decreased health literacy, decreased levels of education, or decreased levels of understanding and cognition. Health literacy is the ability to receive information, to understand that information and to take action. Passive coping strategies are also used by those that have a decreased understanding of what pain is. This means that if pain is mild or is transient, it's more accepted as a part of aging. As we get older, we hurt, and we ache, and it's just life.

Active coping strategies. On the other hand, active coping strategies are employed by those that seek high interaction with healthcare professionals. They trust us. They know what we do. The people that employ active coping strategies are aware of their role as a stakeholder in the management of pain. They also have increased understanding. They are proactive in the management of their pain. They're able to call up their physical therapist or their physician to ask questions or request help. There is increased interaction with a healthcare professional. They're looking for ways to ameliorate the pain. They understand that the buck stops with them. You are likely to have increased adherence with this group of people because they have an increased understanding of pain.