Terms

- Suicide = death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with intent to die

- Attempt = non-fatal, self-directed potentially injurious behavior with intent to die; May not result in injury

- Ideation = thinking about, considering, or planning suicide

- Direct self-harm = e.g. cutting, ingesting with known harm to self

- Indirect self-harm = e.g. refusing food & hydration with known harm to self

I am delighted to be presenting our topic today on suicide and self-harm in the elderly as I feel it is extremely important that we share an understanding of what these terms are. While the definition of suicide, suicidal attempts, and suicidal ideation are well understood, the clarity around the issue of self-harm is much less so. Direct self-harm are those actions such as cutting or ingesting where the individual has known harm to themselves. While indirect self-harm is the act of refusing food or hydration, for example, also with known harm to themself. In this course, we will be focusing our discussion on residential communities and longterm care settings because the incidence of suicide in a closed care environment seems to be the most surprising amongst individuals that I talk with. However, any of these prevention strategies are deployable to home health environments or adult day health settings as well. Please listen for opportunities to adapt and modify the recommendations that I will be discussing for those settings as well. Also, I invite and encourage you to look for opportunities to use and share what you learn here today to persons of all ages and throughout your community because there are a lot of misconceptions about suicide.

The Suicide Scope

We are going to begin by looking at the data to build an understanding of suicides. First, we are going to discuss the incidence of suicide in older adults and look at some graphs from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

CDC Statistics

This is CDC data that is cited in references is also available on the CDC website.

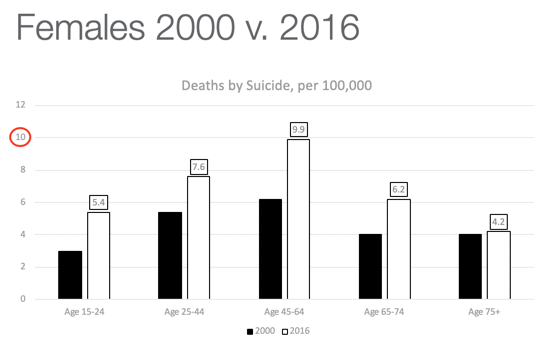

Figure 1. Deaths by suicide per 100,000 in females.

The first bars are the year 2000 and the second bars are the most recent compiled year, which was 2016. We can tell from looking that in all age ranges, there is a higher incidence of suicide than 20 years ago. The second bars are much bigger. In fact, the CDC has calculated an age-adjusted increase across all ages of women to be 50% higher between 2000 and 2016. However, we also see that the shape of the curve here has stayed the same. Death by suicide amongst females is at its highest in midlife. It drops on either side with the lowest incidence in adolescents and in the elderly. Since we are discussing suicide in the elder population, we are going to focus on these last two age ranges. I want you to notice that for women, ages 65 to 74 in both 2000 and 2016, death by suicide in women was higher than it was at adolescence. And since we are discussing suicide in the elder population in the 75 plus range, the two bars are relatively steady between age 65- 74 and 75+. In the recent data (2nd bars), the incidence was far higher in the young senior as compared with that of the older senior, and the lowest point is in the 75+ elderly. Here are a few takeaways. The mental health crisis point for females occurs in midlife, ages 45 to 64, and it reaches a peak of nearly 10 suicides per 100,000 women. For young seniors, it starts to decline, but It remains fairly high before dropping again in the elderly. While it is outside the scope of this course, we can take a moment to consider that many life role changes and transitions affect women uniquely during mid-life that may be impacting these statistics.

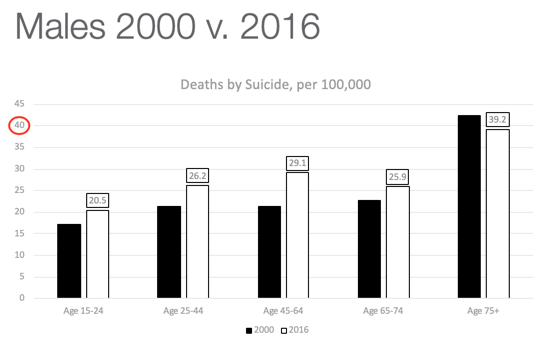

Figure 2 is a chart for males.

Figure 2. Deaths by suicide per 100,000 in males.

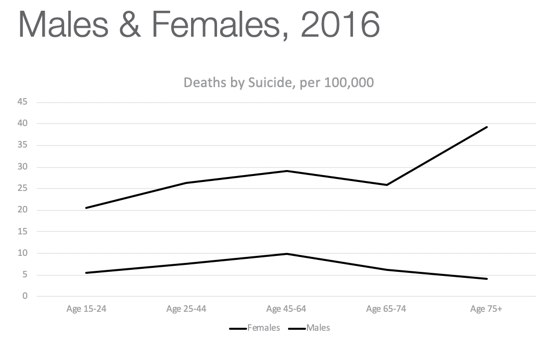

It is important to realize that the X-axis, this red circle here, has been adjusted for the data. Whereas the data for women is 10 per 100,000, this one for males is sitting at 40 per 100,000. We also see a very different overall shape. For the most part, the incidence of suicide is still higher in recent years, though not as dramatically higher, except at midlife. You also see a very slight rise toward midlife followed by a small decline and then a peak in the older senior, 75 and up, in which death by suicide is higher than at any other age. In this view (Figure 3), we pulled off the year 2000 data just to show these trend lines between males and females, males are on the top and females are below so you can compare the rate of suicide male to female.

Figure 3. Deaths by suicide in 2016 of both males and females.

You can clearly see the trend towards a rise in midlife, followed by a slight decline and continued decline in the female but with a sharp rise in elderly males. Again, let's pause and consider the many role changes and transitions that are clearly affecting men over 75, and we will take a moment to discuss those. While all suicide attempts need to be addressed in every age group, statistics show that for a variety of reasons, younger people are more apt to survive their suicide attempts than the elderly. Average statistics show that one death occurs for every 200 suicide attempts in younger individuals.

Figure 4. One death per 200 in younger individuals.

However, due to issues of already declining health and frailty, one in four attempts in the elderly result in death.

Figure 5. One death per 4 in older individuals.

An urgency for this issue has certainly been established. And while we do not have insight into the reasoning for elder suicide, we see in the data that something akin to despair is occurring in the older ages, particularly in older men. The overall suicide rate has increased by 30% since the year 2000. The CDC reports that the rate of suicide has increased by an average of 1% per year between 2000 and 2006 and then grew to 2% per year between 2006 and 2016.

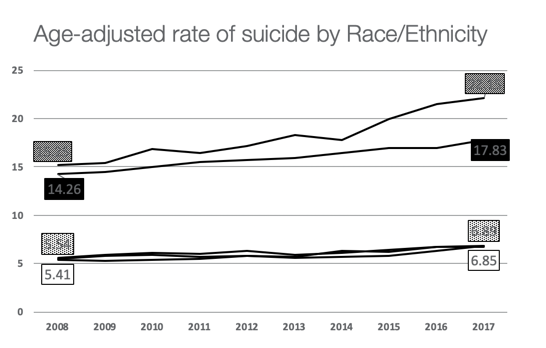

Let's look at some of the possible causes of those increases. Here is a graph looking at age-adjusted suicide by race and ethnicity in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The age-adjusted rate of suicide by race/ethnicity.

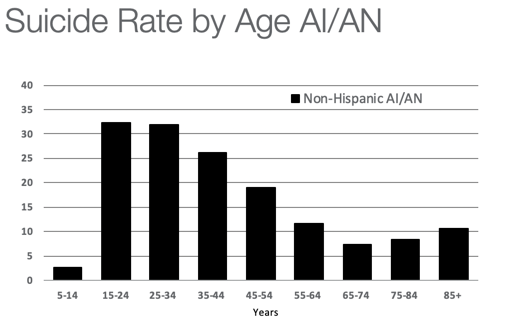

The highest rate of suicide is this top line which are individuals identifying as AI/AN or American Indian/Alaska Native. This is just over 22.15 per 100,000. The line just below shows white non-Hispanic at 17.83. This is both genders together. In contrast, the suicide rate amongst those identifying as Asian Pacific Islander, Black, or Hispanic is down below. It is hard to see, but there are three lines together. These are at a substantially lower rate than either the White non-Hispanic or American Indian/Alaska Native cohorts. Figure 7 shows the non-Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native by itself.

Figure 7. Suicide rate by age for the non-Hispanic, American Indian and Alaskan Native.

The Y-axis is per 100,000 and the X-axis is cohort by age. This tells a very important story as we consider theories of causation. For the American Indian/Alaska Native, suicide rates peak during adolescents and young adulthood and then decline with only a very slight increase in later life, reaching its very lowest point in the young senior, ages 65 to 74. This is a much different pattern than we saw in the general US population for either men or women, where suicide rates are peaking in midlife. And in the US, males remain high through those elder years and then rise significantly in the oldest elder. While the age-adjusted rates show the AI/AN population to have the highest incidence of suicide overall, which we saw on the previous line graph, this graph shows that most of that disparity is occurring in early life. Young AI/AN individuals are at very high risk and if they reach midlife, that risk decreases. We do know that native American culture reveres the tribal elder in a way that white culture does not. The United States is developing a conversation around healthy aging, but for the most part, it remains persistently behind that of other ethnicities. Thus, it is hypothesized that this cultural perspective is a considerable factor.

Male Predictor Variables

- work

- dominance

- risk-taking

- heterosexual presentation

- power

- emotional control

- playboy

- violence

- pursuit of status

- winning

- self-reliance

We also saw that in the male elderly cohort that the incidence of suicide was nine times greater than the female elder cohort. Men are also three or more times as likely to die by suicide at any age than women. Those figures are not unique to the United States. A significant study was completed in Australia and published in 2016. If you recall, this was the peak of the CDC reporting period on our charts. This study used a substantial sample size of almost 14,000 Aussie men. Assessment tools used were the PHQ-9, the same tool we will be discussing in this course for its inclusion in the Medicare MDS, as well as, a standardized measure of traits of masculinity that comes from our care partners in the field of psychology. In this study, researchers compared responses in 11-factor areas. Things were things like a relationship to work, themes of power, status, traits of aggression, et cetera. This was to see if any of those traits would increase or decrease a man's risk of suicidal ideation and planning. While controlling for all other variables, only one was shown to correlate to an increased risk of suicidal ideation and that was self-reliance. The researchers describe that "A man who is normally self-reliant may experience heightened levels of defeat or humiliation if his usual state is threatened in some way." They go on to say that, "Self-reliance may lead to an acute sense of burdensomeness in circumstances of perceived dependence."

Consider for a moment that that is exactly the point at which we provide care when the usual state has been threatened. Those critical points occur when an individual faces a chronic health diagnosis, a change in mobility, or a transition in their living situation. And, as we go on to discuss these and other warning signs and risk factors, you will hear the words humiliation and burden repeated as factors that increase risk. Australia's large sample of men does line up with our understanding of suicide risk as presented in the current light.

Baby Boomers and the Cohort Effect

- 60% higher than previous generations

- Began a decade before the recession

- Life factors as Boomers enter older ages

- economic conditions

- chronic unemployment or underemployment

- increased out-of-pocket spending for healthcare

- increasing chronicity of illness

- Generational paradigms: questioning purpose and meaning

Let's now talk for a moment about Baby Boomers and the so-called cohort effect. We saw from the data that there is a 60% higher incidence of suicide in the Baby Boomer generation than that of previous generations (like the silent generation before the Boomers), and suicide rate began a decade before the economic recession. Although economic conditions are certainly one factor affecting an individual's condition, there are other life factors that Boomers endure as they enter older ages. They experience more chronic unemployment or underemployment than the silent generation. They have increased out of pocket spending for the healthcare that they are receiving along with an increase in chronic illness. Along with pairing that with those generational paradigms that the Baby Boomers have grown up with, they often question purpose and meaning. This creates a cohort in which suicide is seen differently than previous generations.

Celebrity Suicides

- Marilyn Monroe (1962)

- age 36

- depression

- mental illness

- ACEs

- ↑ 12 % nationwide

- Kurt Cobain (1994)

- age 27

- clinical depression

- drug and alcohol abuse

- ↓ in 5, 10, 15-day counts

- Robin Williams (2014)

- age 63

- clinical depression

- drug and alcohol abuse

- new dx. of Parkinson’s

- ↑ 9.85 % across age groups

We also need to discuss the impact of celebrity suicide. I have pulled from each generation a celebrity. Marilyn Monroe died by suicide at age 36 in 1962. She had diagnoses of depression as well as mental illness and what we now call ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences), which was not identified in those years. The adverse childhood experiences that go towards resilience and many other factors are now being researched. Following her death by suicide, there was an increase in suicides by 12% nationwide across both genders and ages. However, this is not necessarily consistent. There are some outliers that we can examine and study. For example, Kurt Cobain's suicide in 1994 at age 27 had the opposite effect. He also had a diagnosis of depression along with drug and alcohol abuse. But following his suicide, researchers were incredibly tuned in to what would happen in this grunge population and they saw a decrease in suicide rates below the consistent average in all of their counts. This was discussed as possibly due to increased coverage in media and the presentation of hotlines and support lines to those that were grieving this loss during that time. It actually brought people together in a way while other suicides tend to spread people apart. Peers reached out to each other to process their grief. Feeling less alone following his suicide actually brought down the suicide rate following his death. However, we do not see this same impact with Robin Williams' death recently in 2014 by suicide. He had a conglomeration of factors including also clinical depression and a history of drug and alcohol abuse, and as later revealed, a new diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Following his death by suicide, there was an increase of near 10% across all age groups. These are the Baby Boomer that we have all had our eyes on.

Suicide Cluster or Contagion

- Several suicides or suicide attempts occur in a region or social group greater than would be expected by chance.

- Some literature report as few as 2 or 3 comprises a ‘cluster’

As we just discussed, this is what creates a suicide cluster or contagion. Several suicides occur within a region, a social group, or a generation greater than would be expected by chance. The CDC has its counts and anything that occurs that is outside of that could be related to this idea of a suicide cluster or contagion. Literature reports that this can be as few as two or three individuals comprising a cluster in a community, for example, or a small cohort. For example, if this occurs in a longterm care facility or a care facility of some kind, it automatically increases the risk of having another. There is a video in course resources that describes this impact following one resident's death by suicide, where the staff of that facility began to hear on the floor that other residents were now considering suicide by the same method. Some stating, "I always wondered if that would work and now I know that it does." That is a suicide cluster.

Suicide Prevention Strategy

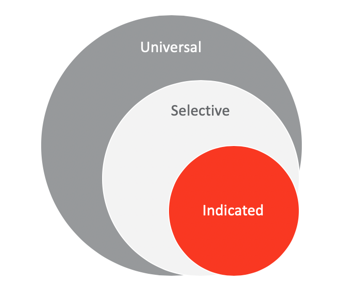

As we discuss suicide prevention strategy, we are going to move from larger groups to smaller groups. Figure 8 is the visual of this.

Figure 8. Visual of the suicide prevention strategy.

Universal Prevention

- Community

- Reduce new cases in large populations

- Local, regional, national efforts

- Increased education & awareness

- Targets skills training

- LTC/Residential

- All residents have access to programming that improves emotional health and coping

- Social networks are healthy between residents

- Access to lethal means is restricted

- All staff receives suicide prevention training appropriate to their level

Universal prevention is prevention which is deployed to the largest population. We see this going out locally, regionally, and nationally to reduce new cases in a large population by increasing education and awareness along with targeting skills training across groups of a population. Whereas, in longterm care, it is the widest possible lens of that residential group. For example, all residents would have access to programming that increases emotional health and coping. We are starting to see universal prevention methods applied to entire communities of elders to address this. Everybody is supported. This includes building social networks that are healthy between residents of all walks of life, restricting access to lethal means, and all staff receiving suicide prevention training that is appropriate to their level. We will be discussing that in a little more detail.

Selective Prevention

- General

- Targets high-risk groups

- Cumulative losses and life transitions

- Increased vulnerability

- LTC/Residential

- Activities to engage men

- Residents with chronic pain and disease

- Residents with persistent sleep disorders

- Residents showing warning signs

Selective prevention is focusing the lens somewhat. In a general community, this might be targeting high-risk groups or those that are more vulnerable to demonstrating risk flags and have increased vulnerability. In a long-term residential community, we see this selective prevention being applied when we see an improvement in activities that in particular engage men. This is something that our communities are not necessarily doing. Yet, the suicide rates indicate that this is our highest risk group for dying by suicide inside of residential care. Along these same lines, we can also target those with chronic pain and disease, have persistent sleep disorders, and any resident showing warning signs. This is developing programming that targets residents that are at particularly high risk based on their profile.

Indicated Prevention

- General

- Imminent risk

- Exhibit red flag behaviors

- Mental illness indicators

- LTC/Residential

- Imminent risk

- Exhibit red flag behaviors

- Mental illness indicators

Then narrowing the focus even further, an indicated prevention is the same between the general community and a care setting. This is targeting individuals that are demonstrating red flag behaviors and have indicators of mental illness or substance use that are at imminent risk.

Risk Factors Vs. Warning Signs

What are explicitly the risk factors versus the warning signs? They are very different things.

Building Awareness

- Risk Factors

- Those things that increase the likelihood that a person may attempt suicide

- Demographic

- Historical

- Documented (EMR)

- Warning Signs

- Red flags

- <80%

- Observable

- Noticeable behavior change

- Even sudden ‘relief’

- Intuitive

Risk factors are those things that increase the likelihood that a person may attempt suicide, not that they necessarily will. They can be demographic, historical, or things that are detected in the medical record. Those are risk factors. They increase someone's risk but not necessarily their likelihood. Whereas, warning signs are those observable behavior changes that indicate an individual's possible decision to die by suicide. These are red flag behaviors. Studies of these warning signs along with interviews with family members and staff show that up to 80% of people demonstrate warning signs, but the individuals close to them did not know to detect them. They are observable. There may be a noticeable behavior change or things that are outside of an individual's particular typical expression. They are largely intuitive. People will say, "I thought something like this, but I could not put my finger on it." The individual was detecting warning signs.

Knowable Risk Factors

- Demographic

- Age

- Veteran status

- LGBTQ status

- Cultural clusters

- Medical Record

- Mental health dx

- Alcohol abuse

- Substance use

- Chronic health dx

- Pain

Knowable risk factors are those things you can know and identify. Again, these may increase an individual's likelihood. When we think back on our celebrity suicides, all of whom exhibited risk factors that were knowable. Robin Williams demonstrated this by his age, a drug and alcohol addiction history, clinical depression, and recent chronic health diagnosis. Each of these was a knowable risk factor. There are also risk factors of veteran status, LGBTQ status, and cultural clusters.

Ask-able Risk Factors

- Undocumented History

- Past attempts

- Family history of suicide

- ACEs

- Access

- to mental health svcs

- to lethal means

- Coping

- Access to mental health

- Prolonged stress

- Situational stress

- Critical transitions

- Loss

Other risk factors may not be present in a medical record, but they are "ask-able." These are past things that are undocumented like perhaps a past attempt or a family history that may not be present in someone's medical record. Along with that is a possible history of adverse childhood experiences. Other things like the individual's access to mental health services or access to lethal means are also risk factors. We can also look at an individual's overall coping style, their ability and willingness to access mental health supports, and the presence of stressors, critical transitions, and loss over time.

Observable Warning Signs

- Feelings

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Anger

- Persistent irritability

- Hopelessness

- Helplessness

- Shame/Humiliation

- Behaviors

- Change in drug/alcohol use

- New med seeking

- Isolating self

- Giving things away

- Sudden joy

- Sleep changes

- Dietary changes

- Escalating self-harm

- Non-verbal cues

It is important to note here as we look at observable warning signs and that depression is not a normal part of aging. Depression is a mental health condition to be discussed and addressed not something to be dismissed because of our own preconceptions about growing older. We see shame and humiliation on this list. What we saw in our prior slides regarding causative factors is noted here as an observable warning sign. This has a particular impact on our male residents as well as in certain cultural groups. Please note that it is not an actual burden or the caregiver's perception of burden, but the individual's self-perception of burden which is unrelated to their actual performance. Irritability, hopelessness, helplessness, and behaviors including new med seeking or new med storing are noteworthy. They may isolate themself and give things away more than you would expect beyond an individual transitioning into a new living situation. They may display sudden joy that is atypical for them. There also may be escalating self-harm.

The Four D's of Suicide Risk

- Depression

- Disease

- Deadly means

- Disconnectedness

This brings us to the four D's of suicide risk: depression, the presence of disease, the presence of deadly means, all combined with disconnectedness.

Prevention Steps for Care Communities

Let's discuss some prevention steps for our care communities.

Designated Staff Education

- Practice suicide screening interviews

- Know warning signs of elevated risk vs. imminent danger

- Activate appropriate actions when elevated risk is detected

- Understand facility policies

- Review training at appropriate intervals

Designated staff education is the most critical component. Practicing our suicide screening interviews until we are comfortable delivering them and knowing those warning signs of elevated risk versus imminent danger. We need to be able to activate those appropriate actions within our facilities when we detect risk. Do we know whom to discuss this with and what the process is? Do we know what our facility policies are? And, we need to review that training at appropriate intervals. This is something that our profession can spearhead or lead within the communities where we work.

All Staff, Every Level

- Identify and respond to warning signs

- Can demonstrate what to do when risk is detected

- Recognize alcohol abuse

- Recognize medication misuse

- Promote protective factors

It is important that all staff at every level receive some level of education to identify and respond to these warning signs. Can every individual throughout the facility identify what to do if a risk is detected? For example, it may be the housekeeping staff that is the one that recognizes that an individual is medication hoarding, but they do not know what to do following its detection. It is important that all staff receive information and education appropriate to their level.

Lethal Means

- Community

- Firearms (more likely ♂)

- Medication (more likely ♀)

- LTC/Residential

- Jumps/falls (more likely)

- Firearms (less likely)

- Medication (equally likely)

- Indirect self-harm…

What are the lethal means that we see in use in longterm care? In the community, we see that firearms are more likely amongst men and medication being more likely amongst women. Whereas, in longterm care and residential sites, we see that firearms are less likely. Facilities, for the most part, are doing a good job in preventing that lethal means, but jumps and falls are more likely. Medication appears equally likely both in the community and in longterm care settings, along with the possible impact of indirect self-harm.

Risk Vs. Protection in the Elderly

- Risk Factors

- Depression

- Number of medications

- Loss of a spouse within 1 year

- Perceiving themselves as a burden

- Chronic disease

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Huntington’s disease

- Chronic sleep disturbances

- Alcohol dependence or ‘misuse’ (35% of elder males)

- Protective Factors

- Optimistic

- Internal locus of control

- Sense of belonging

- Satisfaction with life

- Emotional health programming

Both risk factors and protective factors have been documented in the elderly. Risk factors include depression, the number of medications, and the loss of a spouse within one year. Others include the perception of burden and chronic disease, including new diagnoses of Alzheimer's and Huntington's disease. Again, the newer the diagnosis, the higher the risk. The individual has ideas and concerns about that chronic diagnosis. By the time an individual has progressed in their disease, they may not have the ability to deploy an action plan for suicide. Thus, we see that early in that transition period is the highest risk. Chronic sleep disturbances along with a history of alcohol dependence or misuse co-occur in 35% of elderly males.

Protective factors include a general outlook of optimism along with internal locus of control, a sense of belonging, satisfaction with life, et cetera. What we know about that internal locus of control is that this persists beyond their transition to longterm care or residential communities. That individual with an internal locus of control can say, "I may not have control over the environment that I'm in, but I still have control over some factors of my care." They look for places they still have control even if they do not in their residence. That internal locus of control causes that individual to look for places in their life where it can be sustained, and that is a protective factor.

Facility Policies Regarding Risk

- Policies need to limit lethal means, but not be activity limiting

- More intense facility security was positively associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior. (Low et al., 2004)

- Elevation of watch status over time is an important freedom and resident right.

- Increased level of scrutiny

Facility policies need to target those at risk. Of course, this could be by limiting lethal means but not limiting activity. Research has shown that more intense security is positively associated with depression symptoms and suicidal behavior because more intense security reduces an individual's locus of control. It is a delicate balance between being able to control certain aspects while giving them some control. We, as therapists, can support the individual in having a locus of control over their treatment plan and care activities for example. The therapy we deliver may be the only source of control for somebody. It is so important that our facilities balance this risk versus the level of support. Individuals on "watch status" need to have the ability to demonstrate over time that they are safe. Then, the facility can adjust based on risk factors and warning signs to increase or decrease the level of scrutiny around that individual.

Cultivating Emotional Health

- Wellness programs

- physical activity

- mindfulness

- sleep hygiene

- Activity programs

- engagement

- participation

- Resilience Training

- What is it and how do I implement it?

Programming in a residential environment should focus on emotional health for all residents. Again, this is viewing the entire community with a wide lens. We know that wellness programs, physical activity, mindfulness and sleep hygiene are critical for elder wellness. Activity programs support engagement and participation. But we know from our prior slides, that it is particularly urgent that we address emotional health programming for men, which is our highest risk group. Most of our environments inadequately address the needs of this market. I am going to be talking next about resilience training, what it is and how to implement it.

Resilience Program Hypothesis

- “Since having reasons for living and leading a meaningful life are incompatible with suicide, it could be possible that the realization of important personal goals might enhance hope and meaning in life, two protective factors against suicide.”

- …the…program would be effective in increasing psychological well-being and decreasing levels of depression in the participants with suicidal ideations.”

(Lapierre et al., p.17)

The hypothesis is that having reasons for living and leading a meaningful life is incompatible with suicide. Personal goals might enhance hope and meaning in life, These are two protective factors against suicide. The researchers designing this resilience program, which is deployable in your community, have identified targeting that locus of control and the ability to continue to build and meet personal goals inside of a clinical care environment.

Resilience Program Design

- Week 1: Meeting group members, self-introduction

- Week 2: Discussing the (transition) experience

- Week 3: Inventory of personal goals, intentions, aspirations, and projects. Identification of irrational beliefs about goals

- Week 4: Selection of goals that have a high priority and evaluation of each of them according to different characteristics (effort, stress, enjoyment, difficulty, resources, conflict, control, probability of attainment)

What does that look like? This program has been designed with a different theme each week. The content includes meeting group members, discussing experiences including the transition to the care environment, and talking about overall goals. What are the preconceived ideas about goals? What has been our experience with setting and meeting goals? How might that impact our relationship with goals in elder life? Towards the end of that first month, we work on selecting goals that have a high priority to the individual along with realistically what can we accomplish in the current environment. What resources do we have? What level of control do we have of achieving that goal in this new environment? This is a critical part of developing a realistic goal inside of a care community.

- Week 5: Description of the goal in concrete and precise terms as a target-behavior. Selection of one goal and personal commitment to its realization.

- Week 6-7: Planning of goal-related action (where, when, how), anticipating obstacles and identifying strategies to face them, identifying personal and social resources. Planning should be reevaluated regularly. Suggestions from the group are important at this time.

- Week 8-10: Execution of the plan, persistence toward the goal, facing difficulties with the emotional support of the group. Revision of goal-planning could be necessary and even questioning the priority of the goal.

- Week 11: Evaluation of the outcome and progress in reaching the goal. Evaluation of the learning process.

In the successive weeks, 5 through 11, we go into more in-depth. This might be adjusting the goal over time, looking for ways to modify that goal, or supporting clients to reach their goal. These are all critical steps to building cohesiveness within the group.

Transitioning Safely

Elevated Risk of New Residents

- Highest at the point of transition from home

- Once relocated, ↑ risk within the first 7-8 months

- 12% of newly relocated LTC residents had suicidal thoughts

- 6% at the time of admission

- 2.3% at two weeks following

- 2.9 at two months following

Transitioning into a facility from home has an elevated risk of suicide, and it does not decline very quickly. Another critical thing to realize is that when we say transitions appear to be the tipping point of suicidal risk, it is important that we think about those transitions from the resident's perspective, not from our own. While it might be highest at the point of transition from home, researchers gained insight following the suicide attempt of an elder that was moved out of her usual unit to an attached memory care suite. She had been a long-term resident of the same community. While that initial window of risk had already passed since she first arrived from home, the transition to an adjacent memory care complex, even attached to the same building, was a new window of transitional risk. The person was removed from their familiar environment and care team, and it increased that risk again. You and I might know intimately the staff on that floor or that wing or that unit, but to the individual that is relocating to that unit, it is a brand new transition. It is important that we keep the resident's perspective in mind when we talk about transitional risk. Once the individual relocates, the risk of suicide is at its highest peak within the first seven to eight months following that transition. Up to 12% of interviewed newly relocated long-term care residents endorsed suicidal thoughts. And even at two weeks and two months, there continue to be suicidal thoughts up to that full window of seven or eight months. That is a significant amount of time when we as practitioners feel as though that window has closed. For the individual, it apparently has not.

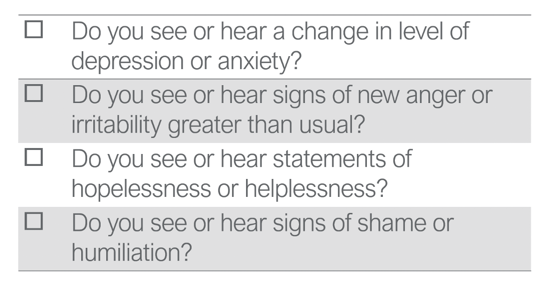

Transition Checklist: Feelings/Mood

I am presenting some transition checklists feel free to take these back to your community.

Figure 9. Transition checklist for feelings and mood.

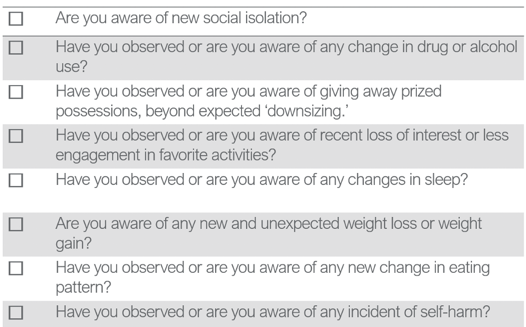

Transition Checklist: Behaviors

Figure 10. Transition checklist for behaviors.

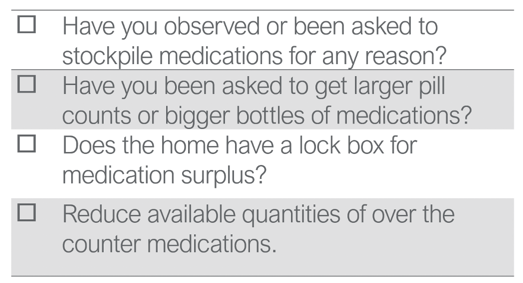

Transition Checklist: Medications

Figure 11.Transition checklist for medications.

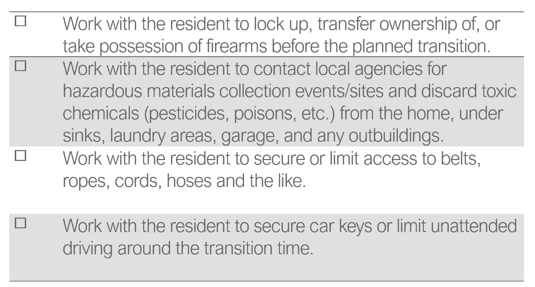

Transition Checklist: Lethal Means

Figure 12. Transition checklist for lethal means.

This may not be valuable once the individual has relocated, but if as a therapist you are spearheading suicidal prevention efforts in your community, that could be a critical resource to provide the family as the individual is transitioning into your care.

Asking About Suicide

Now, we are going to spend some time practicing asking about suicide. Due to the sensitive nature of asking about suicide, you will want to make sure that your interview environment is conducive to discussing the topic. The resident is more apt to feel comfortable talking about private feelings in private spaces versus say the dining room, even if it is empty of others. Again, from the resident's perspective, is this a private space conducive to discussing a significant topic? Of course, we want to ensure that they can hear and they can adequately see us.

Setting Up The PHQ-9 Interview

- Private setting

- Ensure resident can hear

- Sit facing the resident, minimize glare

- Give an introduction

- Assure them that you ask the same questions of everyone.

- Explain purpose = helps design a custom care plan

- Accept refusals, move on to the next

When we set up the PHQ-9 interview, It is important that you provide an introduction and assure them that you are asking the same questions of everyone. It is nothing about them that indicates these questions. The purpose of delivering the PHQ-9 is to help you develop a customized care plan. If they refuse, you move on to the next item. In all of the PHQ-9 questions, the resident is responding to the exact prompt, "Over the last two weeks, have you been bothered by any of the following problems?" The resident responds yes, no, or no response, and gives a frequency of the concern for any yes answer. Frequency response choices are never, one day, two to six days (which is several), seven to 11 days (which is half or more), or 12 to 14 days (which is nearly every day).

Item DO2001: Suicidal Ideation

- Ask openly, directly, and without hesitation

- Ask exactly as worded

Item 1 is at the very bottom of the PHQ-9 and is worded, "Thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way." The key to this question is to ask it openly, directly, without hesitation, and to ask it exactly as worded. Few people would struggle with item D feeling tired or having little energy or have a problem asking about sleep or appetite. Yet, many providers have trouble delivering that same objectivity to Question 1 because it involves suicidal ideation. Asking about suicide does not put the idea in someone's head. This is entirely built upon a myth. Asking about suicide does not put the idea in someone's head. Chances are if they have considered it, you have cracked open the door to safety and healing by starting this conversation. All of the evidence shows that if they have not considered it prior to your asking, it is just another question and the same as asking about sleep or appetite.

How to Ask

- PHQ-9: “(Over the last two weeks, have you been bothered by) thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way.”

How to ask. We have very specific guidance here. The text we are provided is this, "Over the last two weeks, have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?" It is clear and unambiguous. They are going to give you an answer, and it could be yes.

How to Ask a Follow-up/Direct Ask (Vs. Avoidant Ask)

- “Are you thinking about suicide?”

- “Do you have a plan to kill yourself?”

You need to prepare yourself with a follow up to that yes answer as you are not going to mark your box and leave the room. You are engaged at that point in this conversation. How do you ask the next question? "Are you thinking about suicide? Do you have a plan to kill yourself? Have you thought about how you might kill yourself or harm yourself?" That next question needs to be explored. What is the level of their plan? "Do you have a plan? Have you thought about the means?" Discuss this openly and without judgment. We do not want an avoidant ask like, "You aren't thinking about killing yourself, are you?" This introduces personal judgment and shuts down the conversation. That individual now knows that you are not a safe person to talk about their concerns with. Instead, we need to use direct language. "Have you thought about how you might hurt yourself?" We are asking directly without hesitation and using plain language.

If Yes...

- Thank them for their honesty & courage

- Recommended ways to ask the next questions:

- Have you thought about how you would end your life?

- Have you already considered how you access those means?

- Are you thinking of when you might end your life?

- Have you thought about how you would end your life?

- Warm hand-off to staff in charge

- Follow facility policy

If they do answer yes, our first move should be to thank them for their honesty and courage. "Have you thought about how you would end your life?" "Have you already considered how you would access those means? "Are you thinking of when you might end your life?" We need to follow this by a warm hand-off to the staff person in charge, and we should be following our facility policy when we do so.

Direct Response Vs. Avoidant Response

- “Who can help you limit your access to_____________?”

"Who can help you limit your access to that means?" This question is better than an avoidant response like, "Why would you do something like that? You have so much to live for." We are staying objective and keeping our feelings to the side. We are asking and answering directly. We are leaning into the topic.

If No...

- Does your intuition agree?

- Do you detect discrepancies between this conversation and others you have had?

There are a lot of reasons that they may say no even if they have considered suicide. Does your intuition agree with their no answer? Do you detect any discrepancies between this interview and other things you have heard or seen? If they have answered no, you may mark on your PHQ-9 that they have indicated a no answer, but then you may document that you have concerns and recommend a followup interview. A no answer does not mean the topic is complete.

Next Steps in Communication

What are those next steps in communication within your facility? We know that though many residents endorse symptoms of depression, a study was done in 2010 indicating that fewer than 25% of depressed residents in long-term care settings have been accurately identified. There are many reasons for these findings which we continue to see played out in facilities across the country despite the requirement that the PHQ-9 be administered as part of the Medicare MDS with standardized wording and exactly as written. This may be due to incomplete training, discomfort in asking the question directly, or perhaps the uncertainty of the consequences of a yes answer, such as how to complete a hand-off, how to take the next appropriate steps, or even perceived pressure to under-report. It is critical that ethical and compliant care guide the accuracy in reporting of all questions of the PHQ-9 and any variation in this very clear practice standard is a compliance issue. The answer to the question is not a provider's judgment call regardless of the resident's appearance, apparent mood, personal feelings about the person, how you feel conducting the interview, the issue or the question itself, or how you feel about the resident.

Responding to a Yes Answer

If the resident responds yes, the yes is recorded. Regardless of any possible reasons for the under-reporting of depression and suicidal ideation, inaccurate representation of these PHQ-9 questions has potentially life-threatening consequences. It is critical that providers and teams get this right. And, getting it right does not take unique expertise. It takes practice and compassion. It takes asking the question exactly as it is worded on the MDS, asking openly and directly and then accurately reporting the resident's response and activating a change in the care plan if necessary. "There's a person on our team who helps assess these feelings so we can provide you with the best care. Together, we can develop a plan to deal with this. I'll let him or her know to come talk with you further." This is your pivot to the next steps.

The Warm Hand-off

The warm hand-off takes one more essential step to get it right. If you are the provider receiving a yes in addition to recording it accurately on the MDS, you have an obligation to provide a warm hand-off to the person in charge of their care. "I just completed the PHQ-9 with so and so and I have a concern about their wellbeing. They answered yes that they have thought about hurting themselves." You then pass on any related dialogue that took place as part of that interaction. "They thought they would be better off dead." "They thought about harming themselves." "They have considered suicide." You need to report any other details that came up in the conversation. It is very important that you as the therapist document your hand-off encounter with that appropriate staff member because while the PHQ-9 serves as documentation of the presence of depression and possible risk, it does not address the next steps in the activation of your facility policy. It is your professional responsibility to document that the concern was brought to the live attention of the individual in charge of patient care as well as any other identified staff selected by the facility. Even if that PHQ-9 does reflect the resident's suicidal ideation accurately, this is another frequently dropped or inadequately completed step. The person in your care gave you the gift of trust with their honesty and disclosure and the professional responsibility that comes with that trust is to ensure that it affects a change in the care plan.

Identify Risk Throughout a Care Stay

The possibility exists that suicidal ideation will occur at any point in the care stay, not only when that initial MDS is administered. Recall in our earlier slides that two weeks, two months, and in some longterm residents, up to eight months following a transition there continues to be an elevated risk. Following up on any comments or observed red flags is an important step in delivering compassionate care.

Who Hasn't Thought About It?

- Casual ‘death’ talk appears to be an age-appropriate norm

- Staff may not be able to distinguish between casual talk vs. intentional harm

- Listen for specific intentionality

- If concerned, ask directly, without euphemism

One thing that has been expressed is that there is some normalcy in casual death talk amongst the elderly. One interviewed resident in a television broadcast about suicide, which I have linked the end of the course, said, "Who hasn't thought about it?" However, the staff member may not be able to distinguish between casual talk and intentional harm, and it is not their job to do so. It is essential that any talk or red flags be communicated to the care team and followed up. And while this conversation might be occurring in a group or with a peer, it may not be effective to ask an individual at that moment in the dining room or in the lounge when they are surrounded by others. It is important that upon overhearing it you follow up both quickly and directly within that same shift. Doing so can reveal if there is any suicidal ideation behind the conversation that was overheard. Listen for intention and ask directly and without judgment or euphemism. "Are you thinking about suicide?" "Do you have a plan to kill yourself?" Again, asking directly will not put an idea in someone's head, but rather, asking directly and without judgment may reveal a level of despair that you and your care team is equipped and empowered to address.

Language

- Remove from use

- Successful suicide

- Unsuccessful or failed suicide

- Committed suicide

- Suicide epidemic

- Gratuitous use of the word ‘suicide’

- Use instead

- Died by suicide

- Non-fatal attempt

- Died by suicide

- Higher rates, increasing rates

- Refrain from out of context use

I want to bring your attention to some of the current language around suicide. We are using the term died by suicide versus successful or unsuccessful. There is nothing about suicide that is successful. We are using very objective terms like died by suicide or a non-fatal attempt. Committed suicide is no longer in use because it criminalizes the act of someone who is in despair. We are steering away from media-hyped terms such as the suicide epidemic. Instead, we are discussing higher rates or increasing rates because individuals are behind this issue and we are refraining from out of context use of suicide as well.

Resources

I want to bring to your attention to the resources for your own review. Online learners are constantly requesting more practical tools and resources to take back to the workplace. As we close, I want to bring your attention to what those are on the topic we have discussed today. This is where to spend some additional time after this course is over if you are passionate about making an impact on this issue. The direct links are provided to each of these items and membership or subscription is not required to access them.

Newscasts

- Bailey, M & Aleccia, J. (2019). Lethal plans: When seniors turn to suicide in long-term care. Kaiser Health News, Retrieved from https://khn.org/news/suicide-seniors-long-term-care-nursing-homes/

- Public Broadcasting Service. (2019, April 9). The hidden mental health risks for seniors in long term care. [TV episode]. PBS News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/video/challenges-of-aging-1554851202/

Here are two different newscasts that were broadcasted on TV last year. In particular, I want to draw your attention to the PBS news report on the issue of suicide specifically in long-term care and residential communities. It aired last year and I strongly encourage you to go directly to that link provided and watch it after we conclude today. It will significantly add impact to the course material by providing you with the personal and family stories that I was not able to include today for privacy reasons. It would also be an excellent team activity to watch as a group if you are interested in spearheading this work in your facility.

Facility Tools

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Promoting emotional health and preventing suicide: A toolkit for senior living communities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Promoting-Emotional-Health-and-Preventing-Suicide/SMA10-4515

This is a downloadable toolkit that SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. It was developed to assist senior living communities with developing policies and practices. It was published in 2011, but I have been lecturing on this topic to facility administrators nationwide and no one has been familiar with it. Discussions are still lagging in senior communities despite available resources. This is a wonderful tool to support you in bringing the issue to the forefront in your workplace. If you feel like you need something in hand to bring to your administration, this is it. The website has other toolkits for senior centers as well as other focus populations such as LGBTQ and schools and resources in Spanish, et cetera.

Hotlines

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

- The Friendship Line: 1-800-971-0016

Finally, I want to draw your attention to the Friendship Line for those of you involved in home health. This is a dedicated call line and service to adults over 60 or those with a disability making it the only hotline of its kind. Research shows that people do not call crisis lines on their own. The Institute of Aging developed this program which is the only one that reaches back out to older adults. Unlike other crisis lines, the Friendship Line initiates a callback service and schedules a regular interval of outgoing calls to monitor the individual's emotional changes over time and provide ongoing support.

I thank you for your time and attention today in addressing this very important issue.

Questions and Answers

I am very glad of this presentation since I have seen so much of this problem across settings like acute care and home health. I would welcome guidance on addressing denial in fellow staff or patients' families. I would also appreciate guidance on differentiating dementia from depression as well as whether there are ways to promote more extensive awareness of the reality of multiple losses as a very typical experience aspect of aging.

This is a very complicated but very valuable question. I would encourage any of you, again, to spearhead the work inside of your facilities. It is a great place for occupational therapy to be positioned, and there are a number of tools on the websites that I provided at the end of the course including staff training tools, a staff training manual, and many resources specifically around memory care. This course did not address Alzheimer's or dementia in particular, although that is a great pivot point for some additional research. There are many studies happening in this area. It seems to be reaching a critical point. You are welcome to reach out to the email address (teresa.otclubhouse@gmail.com) and investigate each of the resources that you see. I think in terms of guidance on addressing denial in staff and family, it takes somebody that is passionate about the issue to move the training and discussion forward. The more we can openly talk about it amongst ourselves and our teams, the more significant life-changing impact we can have.

Data and Statistics

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, June) Suicide rates continue to increase. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 309 [pdf]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db309.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December 2018. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2017, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

References

Bailey, M. & Aleccia, J. (2019). Lethal plans: When seniors turn to suicide in long-term care. [TV episode] Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/suicide-seniors-long-term-care-nursing-homes/

Lapierre, S., Dube, M., Bouffard, L., & Alain, M. (2007). Addressing suicidal ideations through the realization of meaningful personal goals. CRISIS -TORONTO-, (1), 16. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsbl&AN=RN208418359&site=eds-live&scope=site

Lapierre, S., Erlangsen, A., Waern, M., De Leo, D., Oyama, H., Scocco, P., … International Research Group for Suicide among the Elderly (2011). A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis, 32(2), 88–98. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000076

Loebel, J. P., Loebel, J. S., Dager, S. R., Centerwall, B. S., & Reay, D. T. (1991) Anticipation of nursing home placement may be a precipitant of suicide among the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc., 39, 407–408.

Low, L. F., Draper, B., & Brodaty, H. (2004). The relationship between self-destructive behaviour and nursing home environment. Aging Ment Health, 8, 29-33.

Malfent, D., Wondrak, T., Kapusta, N. D., & Sonneck, G. (2010). Suicidal ideation and its correlates among elderly in residential care homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 843–849. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2426

Mezuk, B., Rock, A., Lohman, M. C., & Choi, M. (2014). Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(12), 1198–1211. doi:10.1002/gps.4142

Morriss, R. K., Rovner, B. W., & German, P. S. (1994) Changes in behaviour before and after nursing home admission. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 9, 965–973.

Ron, P. (2002). Suicidal Ideation and Depression among Institutionalized Elderly: The Influence of Residency Duration. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 10(4), 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/105413702236513

Pirkis, J., Spittal, M., Keogh, L., Mousaferiadis, T., Currier, D., & Spittal, M. J. (2017). Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1324-2

Pullen, J. (2016). A Quality Improvement Project with the Aim of Improving Suicide Prevention in Long-Term Care. Annals of Long Term Care, 24(4), 23–30.

Public Broadcasting Service. (2019, April 9). The hidden mental health risks for seniors in long term care. [TV episode]. PBS News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/video/challenges-of-aging-1554851202/

Citation

Fair-Field, T. (2020). Suicide and self-harm in the elderly. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5183. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com